Lost Kings: DNA Fails to Illuminate Royal Mystery

A skeleton buried under a parking lot. A grotesque mummy head. A gourd encrusted with mysterious blood.

These three disturbing objects have something in common: All have been identified as belonging to long-dead kings, in part using DNA evidence. But despite DNA's reputation as a forensic smoking gun, only one — the skeleton — has escaped serious controversy.

The skeleton, widely accepted as the earthly remains of the English King Richard III, is a bright spot in the often-murky world of ancient DNA identification. Archaeologists identified the body based on multiple lines of evidence, from historical records to telltale battle wounds. On top of it all, the skeleton's DNA matched a living relative of the king's.

The tale of the head and the gourd, however, is not quite so straightforward. In 2010, a forensic analysis suggested the head belonged to French King Henry IV. DNA later linked the head to the blood in the gourd, leading researchers to identify the blood's owner as Henry's descendant, French King Louis XVI. Now, however, a second DNA analysis has thrown those findings into disarray, suggesting perhaps the head and the blood belong not to royalty, but to nobodies. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

The cases reveal the controversy of using DNA to identify the long-dead. And they highlight the problems inherent in studying celebrity corpses: At what point can scientists be sure enough that a contested body part deserves a royal burial?

Calls for caution

The case of Richard III is a prime example. The identification of the skeleton, unearthed in Leicester, England, triggered worldwide interest. As the villainous star of a Shakespeare play, Richard III had built-in name recognition and an international fan base passionate about rehabilitating his reputation. [In Photos: The Search for Richard III]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Every piece of evidence pointed to the skeleton belonging to Richard. Wounds on the bones matched historical records of Richard's life and death. The location of the grave was where it was expected to be. Even DNA testing suggested the skeleton was the medieval king.

It was the DNA identification that grabbed headlines, perhaps because shows like "CSI" portray DNA testing as the height of certainty. But scientists called for caution.

"It seems to me that osteological as well as archaeological evidence is stronger; however, 'DNA evidence' sounds fancier so it looks like they used it as the hook to capture the attention of media," Maria Avila, a computational biologist at the Center for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, told LiveScience at the time. Though Avila did not doubt the identification, she warned that close scrutiny is required to be sure of any ancient DNA finding.

Tricky identification

DNA, which serves as the building and operating instructions for the body, is also a handy way to pinpoint identity — assuming the molecule is in good shape. Ancient DNA, or aDNA, as it's known in the shorthand of scientists, is typically degraded. Teasing useful genetic sequences out of a crumbling, fragmented genome can take decades.

"A nice example is the number of years they needed to identify original Neanderthal DNA in the sample they had," said Jean-Jacques Cassiman, a geneticist at the University of Leuven in Belgium who published a recent study calling into question the identifications of King Henry IV and King Louis XVI. "It took them years of work, of hard work."

The Neanderthal Genome Project, established with the goal of sequencing a full Neanderthal genome, was founded in 2006 after the individual scientists involved had already published several attempts at decoding this extinct human relative's genome. It wasn't until 2010 that the collaboration published a full first draft of the genome. [Our 10 Favorite Sequenced Genomes]

Part of the challenge, Cassiman said, is contamination. Hair, skin flakes and other DNA-bearing bits of modern humans can accidentally end up mixed in the aDNA samples, overwhelming them.

"Ancient DNA is fragmented compared to the contaminating DNA," Cassiman said. "There's very little."

A tale of two kings

Whereas DNA was just a piece of the puzzle linking the Leicester bones to Richard III, when the molecule is the whole case, and other evidence is hazy, genetic identifications become more difficult.

The tale of two French kings is a case in point. In 2010, osteoarchaeologist Philippe Charlier of University Hospital R Poincaré in Garches, France, launched a forensic investigation of a grotesque mummy head owned by private collectors. The head was rumored to belong to Henry IV, who ruled France from 1589 to 1610 and famously converted from Protestantism to Catholicism to smooth his ascent to the throne.

Centuries later, during the French Revolution, the graves of long-dead kings were ransacked and the bodies mutilated and reburied in unmarked pits. Some accounts held that Henry IV was among the disinterred, and his head was cut off in the process.

Meanwhile, Henry IV's descendent Louis XVI met with a similar fate as the Revolution raged — though beheading was perhaps more traumatic for Louis, as he was alive at the time. Witnesses to Louis XVI's execution were said to have soaked handkerchiefs in his blood. One of these handkerchiefs supposedly ended up in a decorative gourd owned by an Italian family.

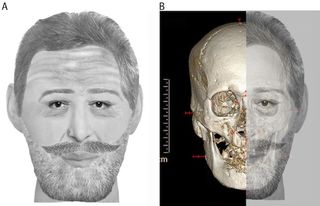

Charlier and his colleagues digitally reconstructed a face based on the bone structure and muscle attachments of the mummy head. According to their work, published in December 2012 in the British Medical Journal, the mummy's features matched those of a cast, or death mask, made of Henry IV's face made just after his death. Later, Charlier extracted DNA from the mummified head.

Earlier this year, scientists led by Carles Lalueza-Fox, a paleogenomics researcher at Pompeu Fabra University in Spain, compared DNA from the head with DNA from the blood found in the gourd. They found a match along the Y chromosome, leading them to announce that the owner of the head and the owner of the blood were related. As the head was thought to be Henry IV's, the blood seemed likely to be his direct descendent Louis XVI's.

DNA drawbacks

Or not. Cassiman's new analysis, published in the European Journal of Human Genetics, argues that neither the blood nor the head came from members of the House of Bourbon, the lineage of Henry IV and Louis XVI.

Cassiman's conclusions are drawn from a comparison of the DNA from the blood and the head with the DNA of three living Bourbon descendants. The living descendants, from different branches of the family, share a Y-chromosome subgroup called R-Z381*. Rather than that subgroup, the Y chromosome found in the blood belongs to a group called G(xG1, G2). The most recent common ancestor linking the two groups would have lived about 10,000 years ago, the researchers calculated. The blood, then, appears to belong to an individual unrelated to Louis XVI.

Because the blood is not from a Bourbon, comparing it with the DNA from the mummified head to make an identification is "completely crazy," Cassiman said.

"You cannot identify two unknowns from two unknowns," he said.

The owner of the head does not appear related to the owner of the blood nor to the living Bourbons through either maternal or paternal lines, he added.

Lalueza-Fox, who led the identification of the blood, said the original conclusions were based on a partial match on the Y chromosome between the blood and the head. However, a single marker that could have been missed in the processing of the DNA would have immediately shown that there was no relation.

"Maybe we were just unlucky," Lalueza-Fox told LiveScience.

"Right now, the most parsimonious [explanation] would be that both Louis XVI's blood and Henry IV's head are false and that the possible paternal relationship we found among both remains is spurious," he said. [Science of Death: 10 Tales from the Crypt & Beyond]

Charlier, who originally identified the mummy head as Henry IV's, is not backing down, however.

"We think it's entirely impossible to try to fit, exactly, a genealogic tree to genetic data," he told LiveScience.

Charlier argues that "nonpaternity events" — when a man raises a child unaware that it is not really his own — make families less genetically linear than a family tree would suggest. Over a period of 600 years or so, he said, familial DNA is bound to diverge from the expected pattern.

"The definition of a family in France is to live in the same house, not to have clearly the same genetic patrimony as the parents," Charlier wrote in an email to LiveScience, using wording he plans to submit to the European Journal of Human Genetics in response to Cassiman's findings.

Cassiman said paternity concerns aren't an issue, because the three living Bourbons share a Y chromosome, suggesting the family line is not broken by illegitimate children.

Unsolved mysteries

What's more, Cassiman said, historical evidence does not point to the head as Henry IV's. Historians are not all convinced that Henry IV's body was among those mutilated in the French Revolution.

But Cassiman's DNA analysis is not irrefutable proof that the head isn't Henry's, either. To come to a definitive conclusion via genetics would take years of work, he said, calling Charlier's conclusions, "a bit too quick."

"If they would ask me to do something more, I would need a serious budget, because I know it's going to take me months and years in order to make something that is believable, that's reliable from this," Cassiman said.

Among Cassiman's concerns is the contamination of the fragile DNA in the head. A documentary aired in France about the identification of the head showed alarming practices during the analysis, he said.

"There are people sniffing on this head, hanging over it, touching it with their nose," he said. "It's completely crazy. I really get upset when I see this."

For now, the researchers are at an impasse. Cassiman argues his DNA findings make it certain the head is not Henry's. Charlier argues the 3D match between the skull and Henry IV's death mask mean it could be no one else's.

Further research may be stymied by conditions unique to the head, Lalueza-Fox added. The first is historical uncertainty about the location of the bodies — no one is sure where Henry IV's remains are. The second are the substances used to embalm the head.

"These substances likely degrade further the DNA or prevent their retrieval, making the analysis of relatively recent specimens more challenging than, for instance, prehistoric remains," Lalueza-Fox said.

So while Britain turns to a debate regarding where Richard III's royal reburial will be, the head of possibly Henry IV (or possibly some random Frenchman) will remain in limbo, Charlier said.

"Sincerely I think this study for me is quite finished, and the story is quite finished because there will still remain, for everybody, a doubt," Charlier said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.