After Burning Man, Leaving No Trace (Op-Ed)

Hetty Chin is a program assistant with the NRDC. This post is adapted from one that appeared on the NRDC blog Switchboard. Chin contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

At 1:00 a.m., along with a large procession of RVs, SUVs, buses and cars — all heavily laden with bikes and rooftop packages of belongings — I was greeted at the gates by a husky woman, adorned in dreadlocks and a jolly smile. I was given a warm embrace and asked to lie down upon the dry remnants of Lake Lahontan, otherwise known as the playa.

There I made a dust-angel and rolled about on the fine alkali powder that would later permeate — no, saturate, my skin, hair, clothes and everything else I brought with me. Thoroughly coated, I rang the bell that would loudly proclaim "I am no longer a virgin!" Having then completed my rite of passage, I crossed into the perimeters of Black Rock City, where I was welcomed to my desert home of Burning Man.

This year, I was one of the record 68,000 participants — better known as "Burners" — to contribute to the community of Burning Man. As a member of the Catmandu art installation (check out our kickstarter here), I arrived early to the festival. For nine days, I was able to watch as the livelihood of the city grew, culminated into a raging multicolored inferno, and then slowly slipped away.

So many experiences took place in those nine days. Ogling at incredibly inventive art, crying from intense laughter, dancing until the blood-red sun rose above the desert horizon, weeping amongst the temple memorials, reflecting on myself and on the norms of society — I had some of my highest of highs and some of my lowest of lows. So, when repeatedly asked, "How was Burning Man ?," I found it difficult to encapsulate an answer. But after long consideration, I finally resolved to answer that the event was "a lot": A lot of sights, a lot of sounds, a lot of moments and emotions, a lot of everything — and in particular, lot of stuff. Enough stuff to form a temporary city, arranged in an arc of concentric streets, that make up two-thirds of a 1.5-mile-(2.4-kilometer)-diameter circle.

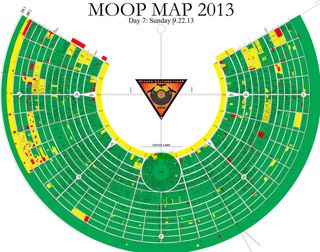

I repeat: a temporary city! At the end of this annual event, the entire city, along with all its stuff, disappears. This happens because Burning Man is held on federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Each year after the festival, the BLM does a site-inspection for Matter Out Of Place, or MOOP for short. A small amount of MOOP is allotted per 1/10-acre inspection site. Passing the inspection warrants a permit for the event to occur in ensuing years.

After Burners leave, a lingering crew of robust workers known as the Playa Restoration Team returns the playa to its unspoiled state. As the restoration team works, they release periodic MOOP maps: graphical representations of MOOP leftovers in all of the camps and art sites. This map is graded on a color scale with green for clean, yellow for okay and red for MOOP-y.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In recent years, these maps have grown greener, an achievement made possible through the concerted efforts of the Burners themselves, guided by one of Burning Man's ten principles: Leaving No Trace. Like other participants, our camp de-MOOPed often and thoroughly, forming human lines to sweep the breadth of both our art installation and campsite, picking up every broken nail head, every shred of carpeting, every splinter of plywood, in an effort to return the playa in better shape than we found it.

The culture and the ethos of the Burning Man community are steered by the principle of respect for the environment, which allows for the profound and magical experiences that I felt, that you'll often hear about, and that you must try for yourself.

Now nearly a month since returning from Burning Man, I am back in the office where I support NRDC's Land and Wildlife Program. At Burning Man's infancy, NRDC — along with other environmentalists — worked with the BLM to help shape the conditions of the sought-after Special Recreation Permits I mentioned above. I'm proud to say that the green MOOP maps we see today are a testament to some of the great work taking place in our organization.

I'll stress the importance of establishing a foundation for minimal impact. NRDC worked on these elemental standards before Burning Man ever grew to the thousands of participants that now gather at Black Rock Desert each year. But beyond these foundations, it is equally important that the community of Black Rock City continues to prevent the deplorable aftermath that could've easily resulted. (For comparison see photos here of the outrageous amount of debris that was found after the Reading Festival that takes place in England around the same time as Burning Man.)

As we decompress, I am repeatedly reminded and awestruck by this astounding feat of foundation and community. If every year, Burners can establish and remove all traces of an entire city, imagine what people can do about their impacts outside of Burning Man.

I have yet to realize how much this consummate experience has affected my daily life, but I hope that Burners take this piece of the Burn with them and try to apply some of the principals of Leaving No Trace into their day-to-day lives, too.

This Op-Ed was adapted from "Respect for the Environment - The de-MOOPing Attitude of Burning Man" on the NRDC blog Switchboard. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.