How Google Street View Could Fight Invasive Species

Google's online street views could help scientists track and fight invasive species over the Internet, researchers say.

Mapping where species are in the world is key to monitoring native and invasive organisms. However, collecting this data can be quite an expensive and time-consuming task.

To help tackle this problem, scientists investigated Google Street View, through which Google supplies panoramic views from the streets of hundreds of cities across the world. Recently, Google Street View has offered vistas of many places off the beaten track as well, such as Antarctica, the Galapagos, the Amazon, Mount Everest's base camp and the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. [7 Amazing Places to Visit with Google Street View]

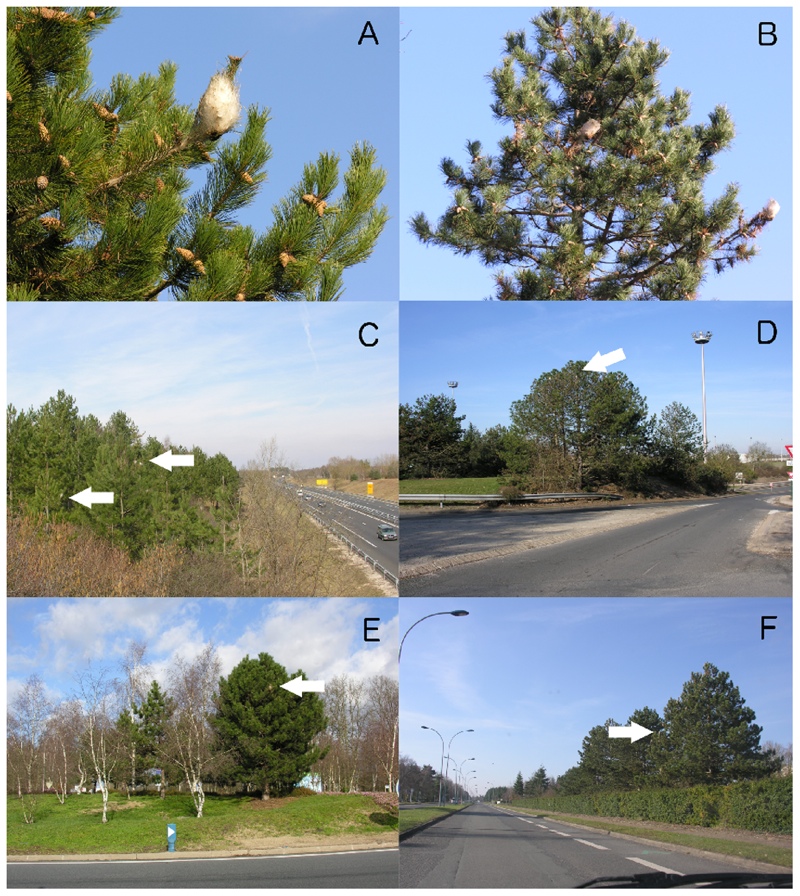

Researchers focused on the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa), whose caterpillar is one of the most destructive animals targeting pines and cedars in southern Europe, Central Asia and North Africa, devouring the foliage of these trees. These social caterpillars spin large communal white silk nests, which are highly visible, making them potential targets of surveys via Google Street View.

"At the beginning of the work, I had the feeling that we were exploring a very unusual way of working — at least one I had never even imagined," said researcher Jean-Pierre Rossi, an ecologist at France's National Institute for Agronomic Research.

The scientists concentrated on a region about 18,000 square miles (47,000 square kilometers) large in France that was recently colonized by the caterpillars. They further divided this area into blocks about 100 square miles (250 square km) in size.

The researchers analyzed data regarding the presence or absence of caterpillar nests collected in these blocks through either direct observation in the field or Google Street View. They found Google Street View was 96 percent as accurate as field data.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, when the scientists investigated a smaller region only about 185 square miles (484 square km) large divided into blocks 1.5 square miles (4 square km) in size, they found Google Street View matched field data by only 46 percent. The researchers note that smaller regions are more likely to have fewer roads covered by Google Street View, and thus less chance to properly spot these caterpillar nests. This effect may be less of a problem in the future as Google Street View's coverage expands.

The researchers note that not all species are ideal for survey via Google Street View, but many could be, such as common tree problems whose symptoms are identifiable from the road, including the horse chestnut leaf miner or ash dieback fungus.

"The data collected by using Google Street View may be useful in monitoring diseases or invasive organism expansion," Rossi told LiveScience.

In January, a different team of scientists found Google Street View could also find potential nesting sites in northern Spain for the globally endangered Egyptian vulture. Altogether, these findings suggest Google Street View could help scientists monitor both endangered and invasive species.

The scientists detailed their findings online Oct. 9 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.