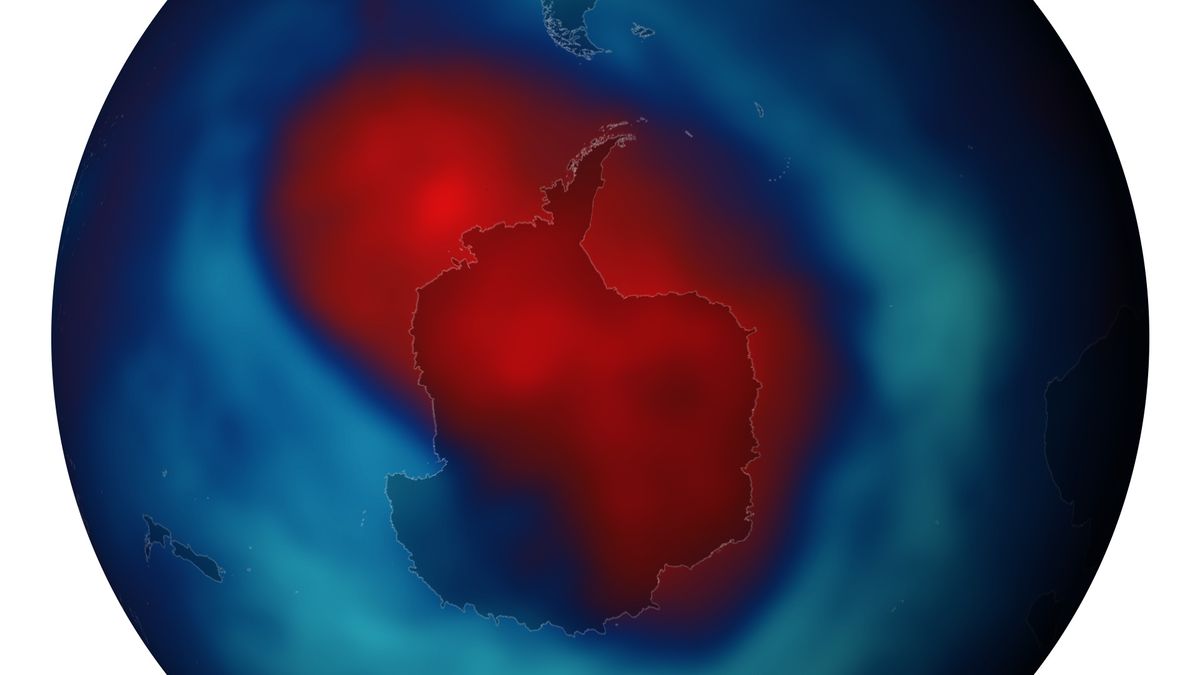

The Antarctic ozone hole reached its biggest extent for the year on Sept. 26, 2013, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced yesterday.

At its maximum, the ozone hole over the South Pole measured a whopping 7.3 million square miles (18.9 square kilometers), making it almost twice the area of Europe. [See the ozone hole form over Antarctica]

The ozone hole is a region of the stratosphere, the second layer up in Earth's atmosphere, where the concentration of ozone, a molecule made of three oxygen atoms, is less than 220 Dobson units (a measure of the density of a gas in an entire column of the atmosphere). The ozone layer, which stretches between 12 miles to 19 miles (20 to 30 km) above the Earth's surface, provides the planet with an invaluable service: Ozone absorbs ultraviolet light, which can help cause skin cancer and sunburn. It is also the culprit behind damage to plants and plankton.

In the 1980s, scientists first detected a depletion of ozone concentrations over Antarctica. The hole forms every year above Antarctica between September and November. The hole developed because of the proliferation of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), chemicals that were once widely used in refrigerants. In several chemical reactions, CFCs bind to oxygen atoms, breaking ozone down into ordinary oxygen molecules.

Through an international treaty called the Montreal Protocol (first signed in 1987), 197 countries have agreed to phase out the use of CFCs, and the ozone layer is gradually recovering. In February, scientists reported that the ozone hole reached a record low and was smaller than it had been the entire previous decade. Scientists estimate the ozone hole will be closed by the middle of the century.

The southernmost continent is particularly prone to ozone depletion because the frigid winds circulating over Antarctica make CFCs particularly good at stripping oxygen atoms away from ozone molecules.

The ozone hole also has effects on climate, because it alters the wind patterns over the icy continent, thereby altering cloud cover and the levels of radiation that reach the Earth's surface there.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.