A Snapshot of High-Speed Photography (And How To Do It) (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

High-speed photography in still images and cinema seems to be the latest rage. And while modern technology has made much of the equipment easily accessible, the basic techniques have been used since the mid-to-late 1800s.

For still photography, high-speed photography means those photographs made with an exposure time of 1 millisecond (1/1000 of a second) or shorter.

For video, it includes events captured with framing rates of 250 frames per second (fps) or faster. This is well above the normal 24-30fps commonly used in video. An event captured at 250fps and played back at a normal 25fps will appear to be slowed down by a factor of ten - see the clip below.

Very early on, photographers realised that a mechanical shutter had definite limitations on how quickly it could operate. In 1856, a British amateur photographer named Thomas Skaife invented a high-speed shutter to photograph cannonballs in flight for the first time. The shutter gave an exposure of 1/50 second - slow by modern standards, but at the time it was quite amazing.

Often, bare electric sparks were used to create a bright enough pulse of light, only a fraction of a millisecond long, to freeze rapid motion.

The modern shutter on a digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) camera is capable of exposures of 1/4000 second (0.25 millisecond), but the small electronic flash units made for these cameras can routinely give exposures as short as 1/40,000 second (0.025 millisecond). This is ten times shorter than the camera shutter.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Three golden rules

I have always felt that good technique in capturing a fast event essentially comes down to three parameters:

- method

- moment

- duration

Put another way, this simply means that your results depend on the combination of how you look, when you look, and for how long you look.

Each is equally important. I use “method” to describe the lighting setup or equipment you might need to stage an event. “Moment” and “duration” relate to the timing of the event and camera and are usually the most challenging parameters to control.

The good news: you can do this yourself

Your DSLR and small flash unit, along with a relatively inexpensive timing device, make it possible for you to capture many small-scale fast events without specialised gear.

Electronic flash rather than shutter speed is one of the main approaches to “method” for high-speed still photography. Transient events require very short exposure times to avoid blur, and this requires a large amount of light during that brief time.

Even with a very fast shutter on your DSLR, there is often not enough existing light to give good exposure. Further, since the shutter, at high speeds, acts as a slit that scans across the sensor, the entire picture is not made at exactly the same time. In some cases this can cause distortion of the moving object in the image.

Flash on the other hand will expose the entire image at once. The downside of flash is that it is a bit hard to pre-visualise the lighting, but it becomes easier with the experience of just a few trial runs.

Flash also helps us get just the right “moment”. The fact that there is a short delay between pressing the shutter button and the opening of the shutter makes it difficult to capture exactly what you want unless you are extremely lucky.

It is much easier to capture the perfect moment by using an “open shutter” technique. Working in a darkened room, the camera shutter is opened on a long exposure, and the flash is fired at the right point in the event.

This is usually triggered by the event itself, linked to some sort of electronic timer or trigger. A quick internet search will turn up at least three readily available units.

Finally, we come to the last parameter: duration. Even if you have synchronised your camera and event exactly, any exposure that is too long will still give a blurred image.

Again, this is where modern handheld flash units truly shine. By reducing the power output, you generally reduce the duration of the flash and achieve exposure times approaching 1/50,000 second. Some of the best units for this are the less expensive “manual only” models that can often be found secondhand.

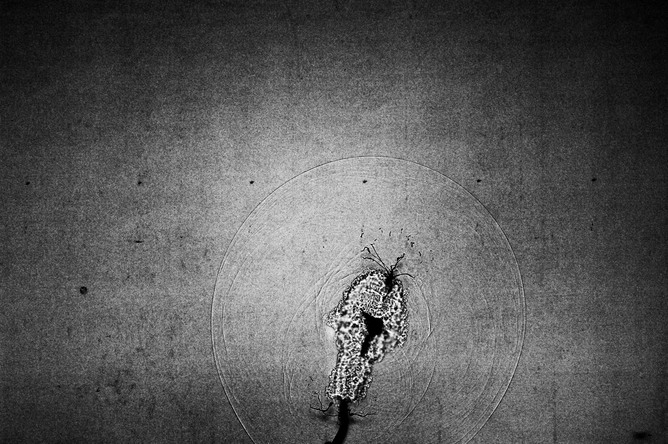

The photo above is a little different: it’s a shadowgraph image of the sound of a bursting balloon. The circle you see is essentially the sound wave, or air pressure wave, that we hear and feel when the balloon ruptures.

This image was captured with an open shutter technique on a DSLR, using an electric spark light source with a duration of 300 nanoseconds - a third of a millionth of a second. That sound wave is moving at about 340 metres per second.

DIY high-speed video is harder

The same three parameters - method, moment and duration - are at the heart of high-speed video or cinematography. The biggest difference from snapping still photography is that all light sources need to be on continuously while maintaining minimal flicker. Sunlight is often the best light source.

Unfortunately, the high cost of cameras and lighting needed in a studio setting can easily push high-speed cinematography beyond the budget of many photographers.

Useful and artistic

There are many scientific applications for high-speed photography. Aerospace and automotive research, manufacturing and human performance in sport are a few examples. In the cinema and television industries, it has become a primary artistic tool.

<

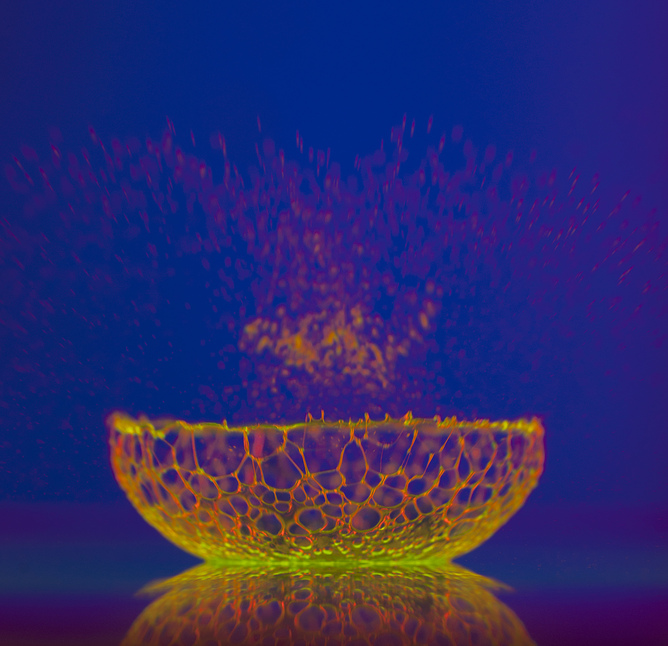

High-speed photography crosses the chasm that sometimes separates art and science, showing us the intrinsic beauty that exists in the order of nature.

Is it science or is it art? I believe the answer is “yes”.

Phred Petersen does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.