Mystery Radar Blob Reveals Odd Man-Made Phenomenon

On June 4, meteorologists in Huntsville, Ala., noticed a "blob" on their radar screen that looked like a strong thunderstorm, despite the fact the sun was shining and not a drop of rain could be found within a few hundred miles. After some sleuthing, and several wacky explanations, the scientists have identified the culprit.

"Our operational meteorologist spotted it on radar immediately and initially thought he was caught off-guard by a pop-up thunderstorm that wasn't in the forecast," Matthew Havin, data services manager at weather technology company Baron Services, told LiveScience in an email. "Soon after that point we had numerous people from around Huntsville (and even other meteorologists from other states) calling and e-mailing us trying to determine what was going on at the time."

And some of the theories put forth to explain the mysterious blob were doozies, from the conspiracy theory that it was the result of a top-secret ground-based transmitter to interference from a nearby utilities substation. [See Images of the Mysterious Radar Blob]

"My favorite explanation that we heard right away from someone in the general public was that it was caused by 1,000 ladybugs that were released by the Huntsville Botanical Garden earlier that morning," Havin said. "It would take many millions of ladybugs to really show up on a weather radar, and it wouldn't look the same as what we were seeing," said Havin, who described the radar-blob tale at the annual meeting of the National Weather Association this month in Charleston, S.C.

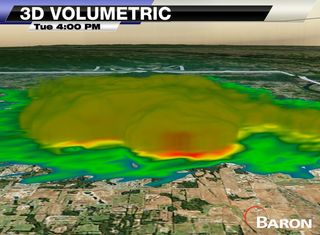

When the team looked at the blob using standard weather radar, all indications were it was a strong thunderstorm. Then they turned to so-called dual-polarity technology developed in the last few years by the National Weather Service. This advanced radar allows scientists to scan in both the horizontal and vertical directions.

They found the blob was not nature-made, after all, and was likely so-called military chaff, or reflective particles used to test military radar.

"What we were able to see from the dual-pol radar data looked similar to military chaff cases previously, but the primary difference was that the winds weren't blowing the stuff away," Havin said. "The releases were happening primarily below 3,300 feet [1,000 meters] above the ground and the low-level winds that afternoon were almost nonexistent (less than 3 mph [4.8 km/h]), so the chaff was basically pluming outward over a good portion of the Huntsville metro area."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, the chaff was visible on their radar for more than nine hours, and the news stories lingered even longer.

"Officially, Redstone Arsenal disclosed that it was a military test using RR-188 military chaff," Havin said, referring to aircraft used to spread a cloud of aluminum-coated silica in the case of RR-188.

The cloud can confuse radar-guided missiles, for instance, so they miss their targets.

"My goal was just to show in greater detail how the weather that day was causing things to look the way they did with the chaff release," Havin said of his talk at the NWAS meeting.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.