Paying Kidney Donors Is Cost-Effective, Researchers Say

The idea of using financial incentives in organ donation, such as paying kidney donors, has been subject to heated debate. Now, a new study shows that using this strategy to address the shortage of kidneys would be less costly and more effective than the current organ donation system, researchers say.

In the study, researchers found that assuming a payment of $10,000 and an increase of kidneys available for transplantation by 5 percent, a strategy of paying living donors would save the health system $340 over the lifetime of each patient, compared with the current organ donation system. The study was published today (Oct. 24) in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The savings come from lower costs and improved health outcomes over the recipient's life. "Transplant has a higher upfront cost, but the yearly maintenance cost is lower than dialysis," said study author Lianne Barnieh, a researcher at the University of Calgary. [The 9 Most Interesting Transplants]

A 5-percent increase in donations would mean an additional 5 kidneys transplanted yearly for every 100 transplants currently performed, and would improve patients' net health by gaining 0.11 quality-adjusted life years on average over a patient's lifetime.

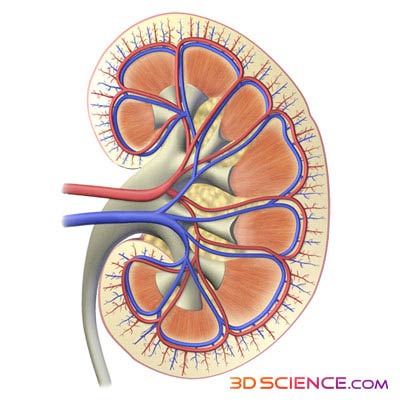

Dialysis or kidney transplantation are the only treatment options for people whose kidneys have failed and are no longer able to remove wastes from the blood. Currently, about 98,000 people are on the national waiting list for kidney transplantation, whereas about 17,000 kidney transplants, mostly coming from deceased donors, were performed in 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Among several suggested strategies to make more kidneys available, researchers and advocates have proposed using financial incentives.

But before exploring the legal and ethical challenges around paid donations, researchers should first determine whether such a strategy is cost-effective, Barnieh said. "If it's going to cost the health system too much money, and not improve outcomes for the patients, there is no point going forward with that."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ethical concerns and practical challenges of such a strategy include opposition from religious groups who oppose the sale of organs.

"A large number of people would not support this strategy and may withdraw from the system," said Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University School of Medicine's Division of Medical Ethics. Although many would like to see an increase in organ donations, with this strategy, "you are playing with fire," Caplan told LiveScience. The argument could become politically charged, like the pro-life and pro-choice divide, he said. "You don't want to make organ donation into an abortion debate."

Another negative consequence of setting up a government-regulated organ market is losing the credibility to criticize exploitive human organ trafficking that happens in some developing countries, Caplan said.

In the payment strategy, any money paid to donors is not technically used to buy the kidney, but is rather thought of as compensation for the pain and suffering of undergoing major surgery.

"Part of the reason we chose $10,000 was that we didn't want it to be so much money that it would change someone's life completely," Barnieh said. "We didn't want it to be a persuasive tactic, but a compensation for the pain and suffering. And to tip the balance of those who are maybe considering donation."

However, this may not prevent exploitation of people desperate for money, critics say.

Caplan said that systems that operate under "presumed consent," in which people are donors by default but can opt out, is likely the best strategy to expand the pool of organ donors. This method has shown impressive results in countries, like Spain, that have adopted it.

"We presume people do not want to be donor. We should turn that around," he said. "People who don’t want to do it can opt out, and carry a card."

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.