Images: Artifacts from Extraordinary Women in Science

400 Years of Women in Science

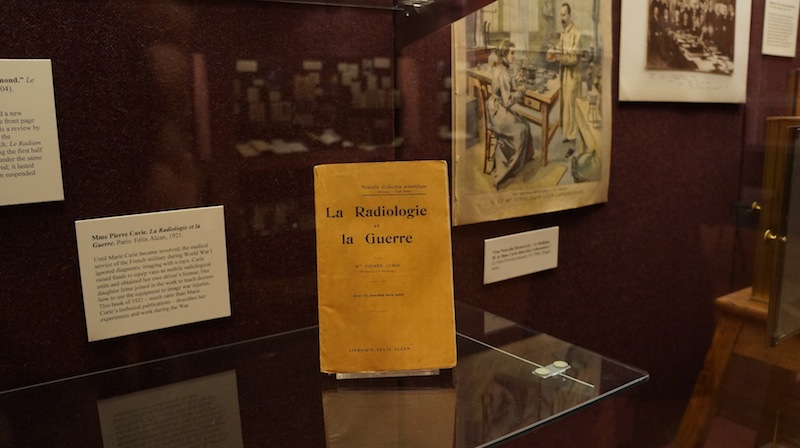

An exhibition at New York's Grolier Club, "Extraordinary Women in Science & Medicine: Four Centuries of Achievement," gathers artifacts and manuscripts related to some of the greatest scientific minds of the last 400 years. This image shows Marie Curie's book about her experiences during World War I, when she helped the French military use x-rays to identify soldier's wounds. Curie, who discovered radioactivity, is one of the most famous scientists of all time, but many of the other women featured in the show are not as well known.

Marie Meurdrac, Chemist

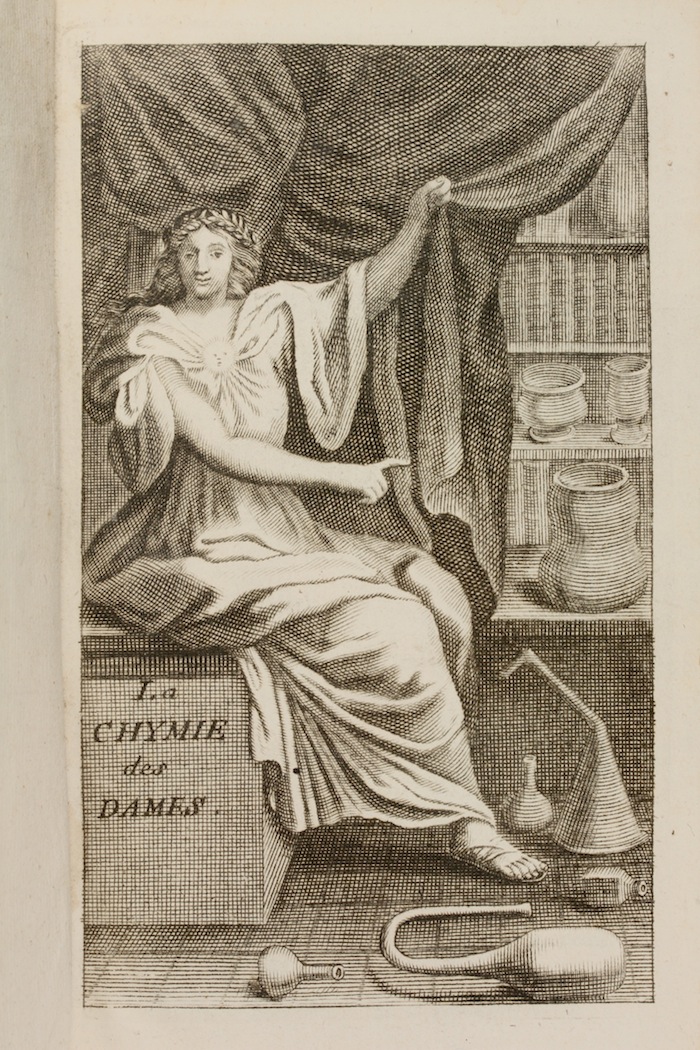

This engraved frontispiece was published in the third edition of Marie Meurdrac’s 17th century book of practical chemistry, "La Chymie Charitable et Facile, en Faveur des Dames." Though hesitant to publish at first, largely because of her gender, Meurdrac declares in her forward that "if the minds of women were cultivated like those of men and if enough time and expense were spent to instruct them, they would be equal to those of men."

Louise Bourgeois Boursier, Midwife

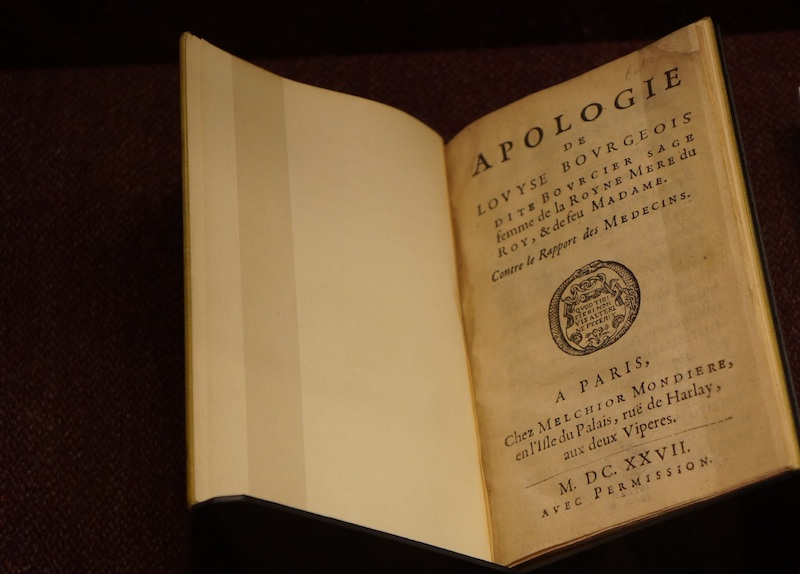

Louise Bourgeois Boursier (1563-1636) was a midwife for French royalty, including Queen Marie de Medici. Boursier was highly respected and wrote extensively about the art of midwifery, outlining the best procedures for normal and difficult deliveries. But she was accused of malpractice when Marie de Bourbon-Montpensier died a week after childbirth. Boursier defended herself in a short book, shown here.

Beevers-Lipson Strips

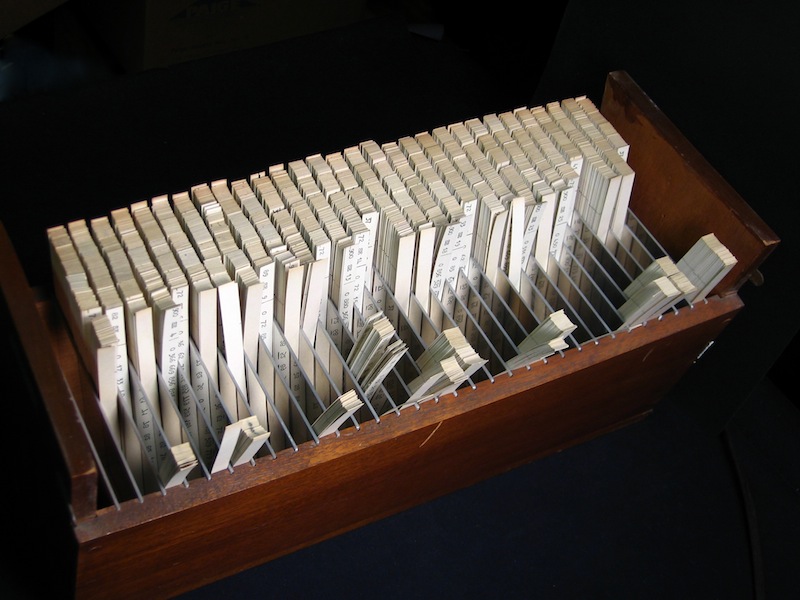

British chemist Dorothy Hodgkin developed protein crystallography and deciphered the structure of important biological molecules like penicillin and insulin. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1964 and in her Nobel lecture, Hodgkin mentioned how important Beevers-Lipson strips were making calculations in her early work. A set of these pre-electronic devices were borrowed from one of Hodgkin’s Ph.D. students.

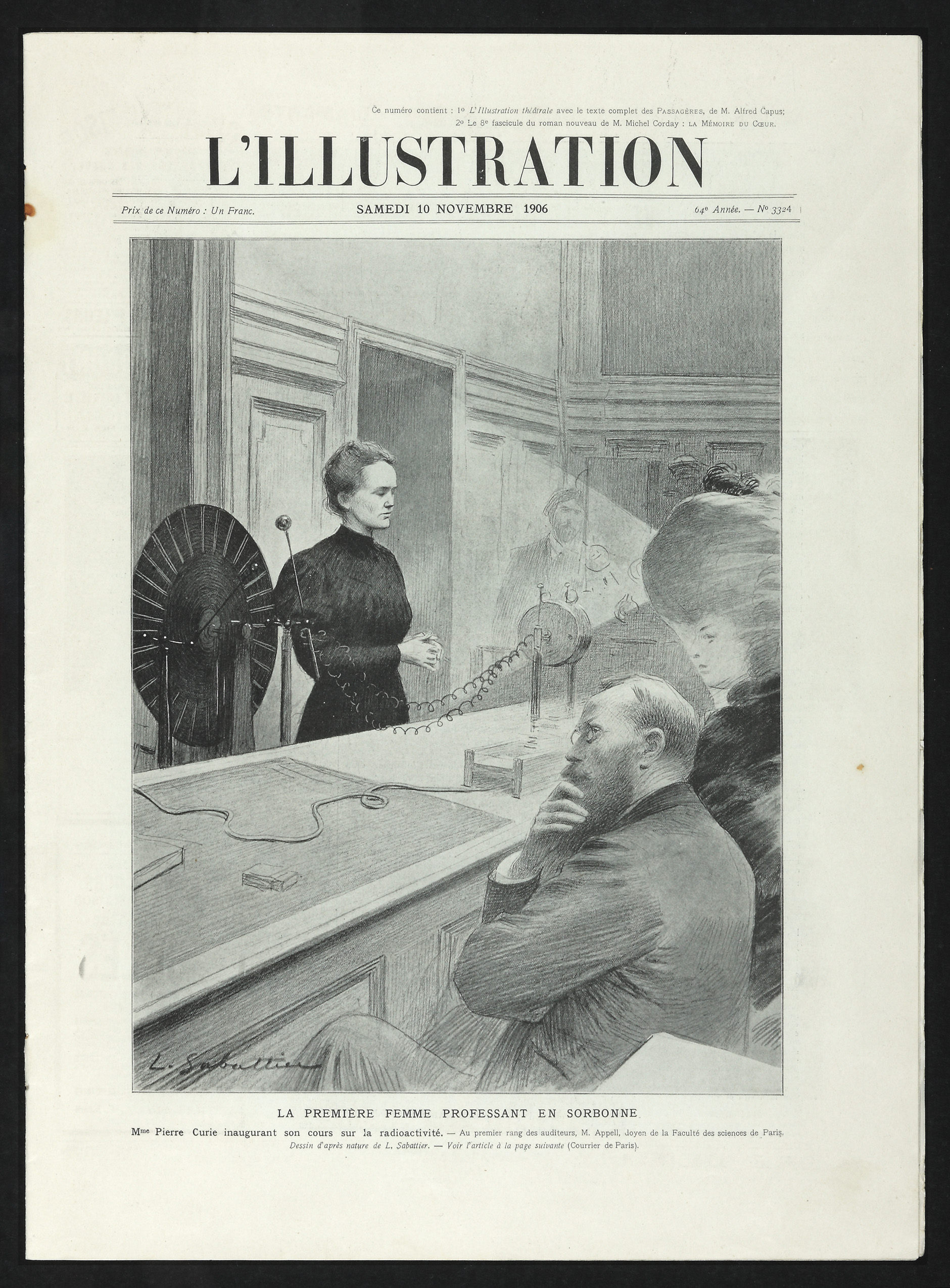

Marie Curie

Upon the death of Pierre Curie in a street accident, Marie Curie was named his successor to the chair of physics at the Sorbonne. It marked the first time a woman became a professor at the French university. An artist in the audience for her inaugural lecture created this drawing for the magazine cover of L’Illustration in 1906.

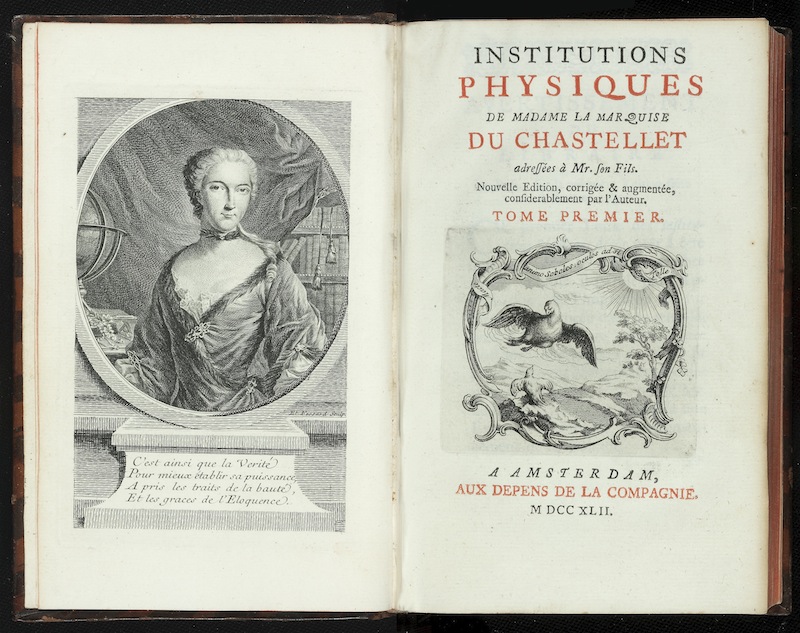

Émilie du Châtelet, Physicist

In 1740, Émilie du Châtelet published "Institutions de Physiques," which was the first theoretical physics text to be printed in France in more than 60 years. This is the portrait frontispiece and title page to the second edition of the book, published in 1742. Du Châtelet later wrote the first French translation of Isaac Newton's "Principia" as well as 287 pages of commentary, in which she explained problems of gravitational attraction and challenged the leading French scientists of her day who thought Earth's poles were elongated.

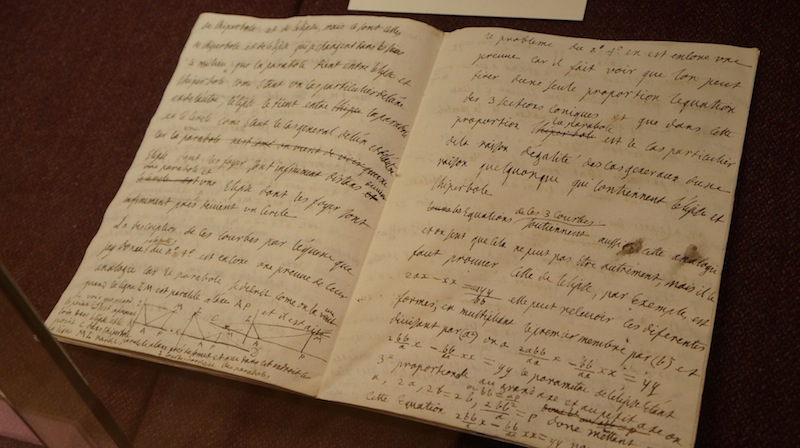

Du Chatelet's Notebook

This workbook contains text, drawings equations that Emilie du Châtelet used to prepare to write about conic sections in her translation and commentary on Newton's "Principia."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

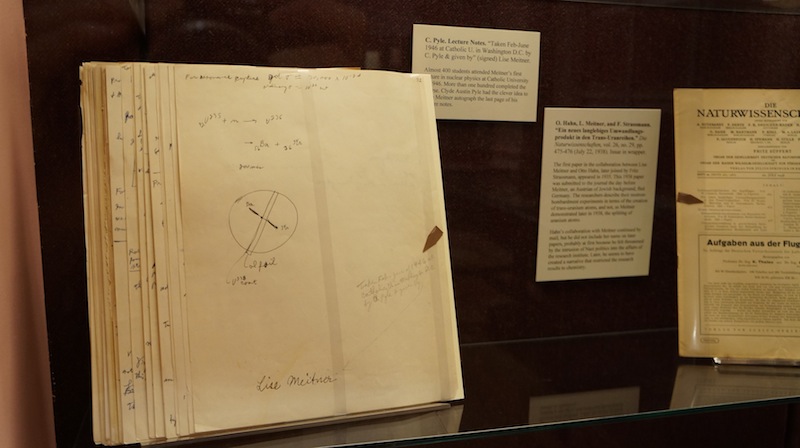

Lise Meitner's Autograph

Physicist Lise Meitner, who played a huge role in the discovery of fission, came to the United States in 1946 to lecture for a semester at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., where one student apparently had enough foresight to ask for her autograph. His signed lecture notes are on display.