Where Does It Go?

Inside Science Minds presents an ongoing series of guest columnists and personal perspectives presented by scientists, engineers, mathematicians, and others in the science community showcasing some of the most interesting ideas in science today.

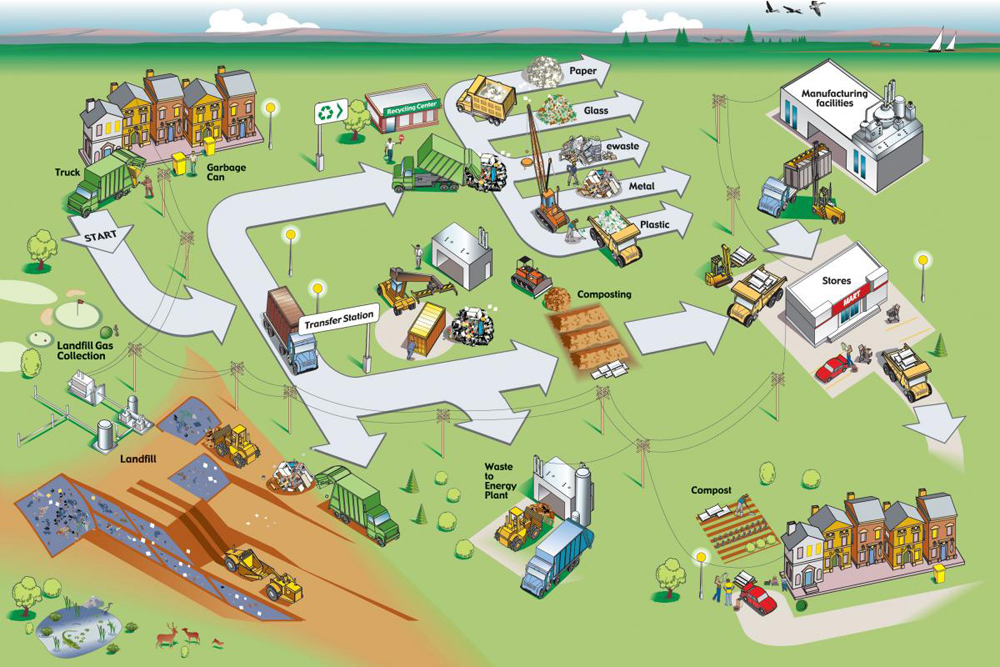

(ISM) -- A soda can, a plastic bottle and a paper bag fall into a bin. This isn’t the beginning of a joke, but rather the beginning of a journey these items will take from a curbside bin to a sorting plant, through a maze of conveyor belts, screens, optical sorters and powerful magnets to meet their fates—becoming recycled.

Millions of Americans participate in recycling programs, but many have no idea what happens to their old cans and paper once it leaves the curb. Where does it go? How does it get there? And what happens to it? Some people do not even believe that the stuff gets recycled. Rest assured, that stuff is getting to the right place through a very modern, technologically innovative process.

During World War II, recycling was a common practice and even considered patriotic. Participation waned following the war, though recycling never truly disappeared. In the 1970s, efforts by the city of Berkeley, Calif., coinciding with the emergence of Earth Day, reframed recycling as an environmental practice more than a patriotic one. Since then, recycling our waste into new products has shed its “hippie” roots to become a major component of most modern waste management programs.

Once upon a time, recycling meant packing materials into the family station wagon and hauling them off to a recycling center. Yet in thousands of communities today, curbside collection—placing your recyclable material into bins for curbside truck pickup by the same waste companies that pick up your household trash—is now the most common collection method. Recycling rates are higher than ever, in part because of these innovations and advances.

As curbside pickup has flourished, single-stream, or “zero-sort,” recycling, which emerged in the late 1990s, is also picking up steam. While some recycling systems still require consumers to separate their recyclables, single-stream consumers use a single bin for all their recyclable materials — newspapers, aluminum soda cans, plastic water bottles, glass containers and cardboard. This provides the system with greater flexibility. Materials can be added to the list of accepted recyclables without adding more containers or sorting protocols for the resident.

If all the recyclables are combined in the same bin, where do they go, and how are they sorted? Is it truly “zero-sort?” Thanks to modern technology, people don’t have to sort recyclables by hand—it’s all done at a plant. Single-stream recycling is driven by cutting-edge, mostly automated technology at state-of-the-art complexes known as Materials Recovery Facilities, or MRFs (pronounced “MeRFs”). There are more than 200 single-stream MRFs operating around the country.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From the outside, most MRFs look like large industrial buildings, often with trash trucks queued up outside, ready to drop off their loads of recyclables. Workers direct the trucks to tip their loads inside the building. From there, a loader will transfer the materials onto a conveyor belt, which will take them to its first sort – generally a series of screens to separate the fibers, such as cardboard or newspapers, from the containers. The container conveyor will then go through a “manual sort,” where workers will pull out trash or material that is incorrectly sorted.

Further along the conveyor belt, magnets will pull off steel items, which are then sent to a container. Of course, aluminum cans are not magnetic. Instead, they are separated by what is known as an eddy current separator. Eddy currents are electric currents that induce magnetic fields, which then repel the aluminum cans, flinging them off the conveyor into a waiting container. Air classifiers, industrial machines that use air to sort objects of different sizes and densities, float the remaining plastic over a gap in the conveyors, while the heavier glass items unaffected by the fans fall into containers below.

Plastic items still require further sorting. Modern facilities employ optical scanners to detect the type of plastic and then blow the different types onto the correct conveyors for final baling. Now that everything is sorted, the recycled materials will be baled, shredded, crushed or compacted before being shipped to manufacturers to be repurposed into new products.

MRFs are extremely effective in sorting recyclable materials from “residuals,” which are any materials that cannot be recycled. A residual can either be material that is not recyclable (such as a ceramic plant container) or material that cannot be recycled because it became excessively soiled. There is no real quantifiable standard for whether materials are “too soiled,” so if a recyclable cannot be cleaned, it should likely be thrown out. For example, used, greasy pizza boxes should be discarded, though unsoiled box tops can usually be recycled. The bane of many single-stream MRFs is the lowly plastic bag – they can jam the machinery and slow down the processing.

For most single-stream systems, about 90 percent of the materials collected can be recycled. A typical MRF manages nearly 100,000 tons of recyclables a year, and their equipment evolves continuously, to allow more types of materials to be recycled.

What does this technology contribute to recycling’s effectiveness and impact? Single-stream systems have beneficial impacts on economic, environmental, efficiency and participation considerations. While initial setup costs may be higher than other options, most communities switching to single-stream do so for greater convenience and savings in the long-term. Single-stream systems are more simplified, more efficient and promote greater recycling-program participation. They have also led to greater materials recovery rates and, because they are streamlined, lessen the environmental impact of emissions and the amount of waste going to landfills.

Single-stream recycling is just one method that municipalities and private waste companies may implement, and it may not be the best option in every circumstance or for every community. However, there has been a marked positive growth in recycling rates—with millions more Americans participating in more than 8,600 communities nationwide today—since single-stream went mainstream.

Further, both the tonnage and percentage of recycled waste in the United States have increased over several decades, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. EPA data from 2011 shows that Americans recycle more than one-third of their waste, nearly 35 percent, compared to 6.4 percent in the 1960s. This is a jump from 5.6 million tons to 86.9 million tons recycled.

If your community manages its recycling through a single-stream process, you might be able to learn more about the system and even visit a MRF for a tour. See for yourself how the recycling story plays out, from bin to baler.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics. Anne Germain is the waste and recycling technology director for the Environmental Industry Associations, the national trade association representing America’s private sector waste and recycling industry. She has two decades of technical experience in the field and previously served as the international president of the Solid Waste Association of North America and the engineering and technology chief for the Delaware Solid Waste Authority.