Scientist's Quest: Save Forgotten US Missile Sites

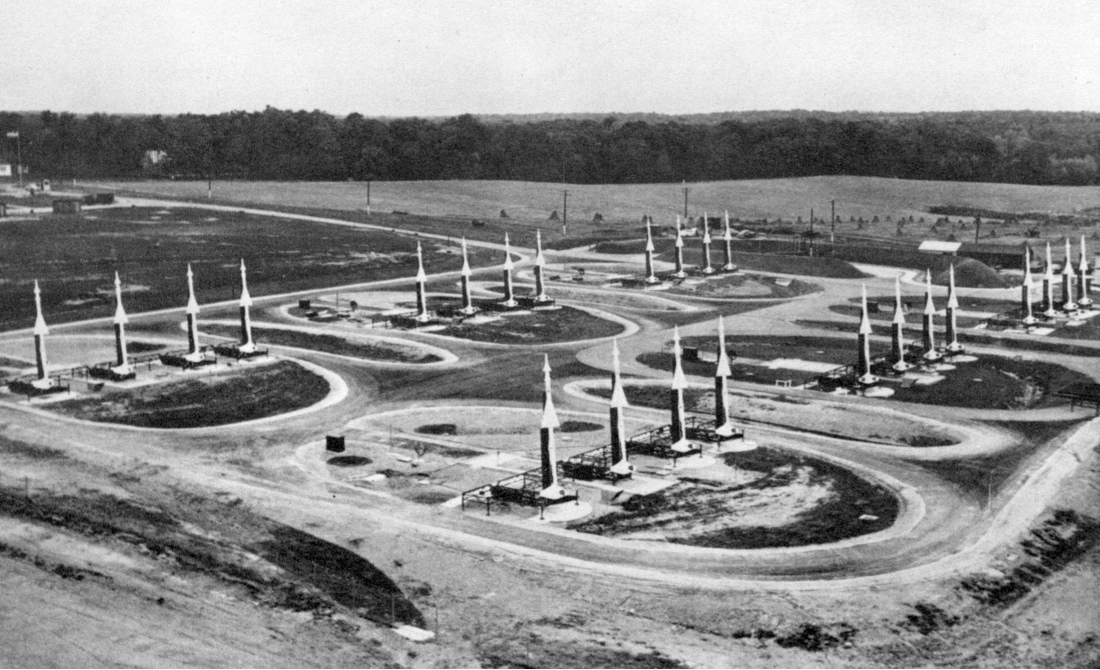

DENVER — The Nike missiles were a key part of the U.S. national defense system from 1954 to the 1970s. At close to 300 sites around the country, supersonic surface-to-air missiles sat ready to launch, protected by soldiers and German shepherds. Some missiles carried nuclear warheads, even though they were next to homes in cities from Los Angeles to Chicago.

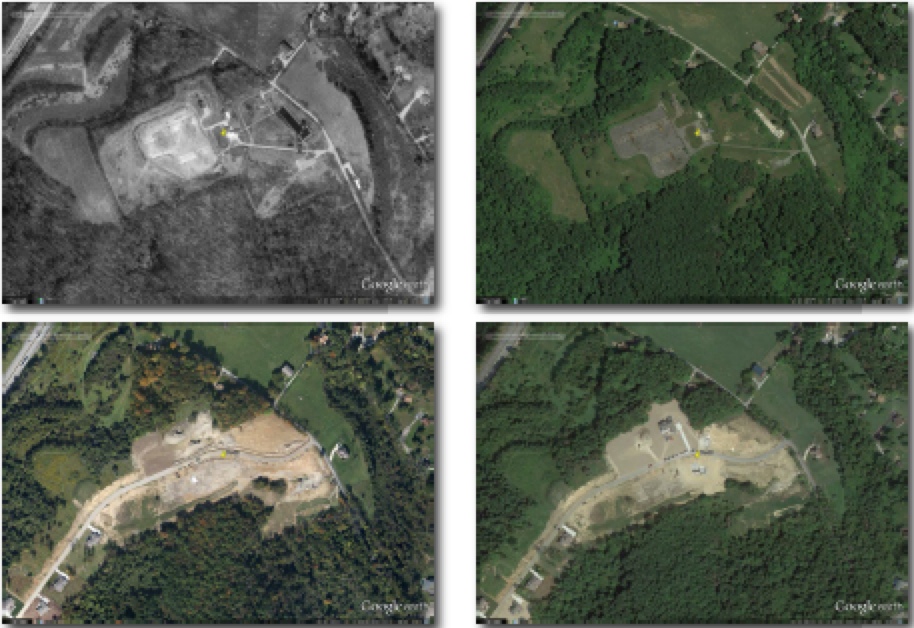

The advent of long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) made the Nike missiles obsolete. Now, the abandoned launch sites are quickly disappearing from view. Some were sold and redeveloped, some repurposed by the military, while others are simply being reclaimed by nature. A base in southwest Ohio is currently for sale to anyone with $279,000. Another is a low-security prison in Virginia. In Pennsylvania, a couple of luxury houses will soon cover a former launch site.

"They're disappearing. Stuff is under walls, it's dug up and houses are built on it, and pretty soon there aren't going to be any of them around," said David Tewksbury, a GIS (geographic information system) specialist at Hamilton College in New York, who hopes to preserve a visual record of the launch sites before they vanish. "If we can keep a record of some of it, that would be pretty cool." [See Photos of the Nike Missile Launch Sites]

Tewksbury presented the early results of his personal preservation project Sunday (Oct. 27) here at the Geological Society of America's annual meeting.

Tewksbury said he is just old enough to remember the reason for the Nike missiles: the threat of a Soviet invasion. But he never knew that he grew up 8 miles (13 kilometers) from a missile launch site.

Three months ago, Tewksbury's father asked him to research the history of a strawberry festival in Wayland, Mass., his hometown. That's when he went down the rabbit hole. A link in his search results led to information about the Wayland missile launch site, a defensive site for Boston. Since then, Tewksbury has combed through hundreds of Google Earth and historic air photos, as well as declassified data and personal accounts posted by Army veterans at nikemissile.org.

"It became like eating chips. I'd see one and go look for more information and find another," Tewksbury told LiveScience. "It's pretty amazing when I look back at it," he said. "The whole East Coast was just essentially a continuous curtain of missile protection."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An expert in compiling complex geographic information into simple, beautiful displays, Tewksbury plans to build a geo-referenced database that allows anyone to research the Nike missile sites through Google Earth. Click on a missile site and a visitor will bring up historic photos and archival information. He intends to give the files to the Nike Historical Society, he said.

The Nike missiles were meant to guard against an attack by Soviet bombers. Each installation had a fleet of missiles and a separate radar site. The missiles were stored in underground bunkers and raised only for maintenance or firing.

"In Cleveland, it was right there in the neighborhood, the kids were probably playing baseball right there, and if they hit it over the fence, [perhaps] the soldiers would throw it back over," Tewksbury said. "In Chicago, they were part of the landscape, they were part of the neighborhood."

EmailBecky Oskinorfollow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.