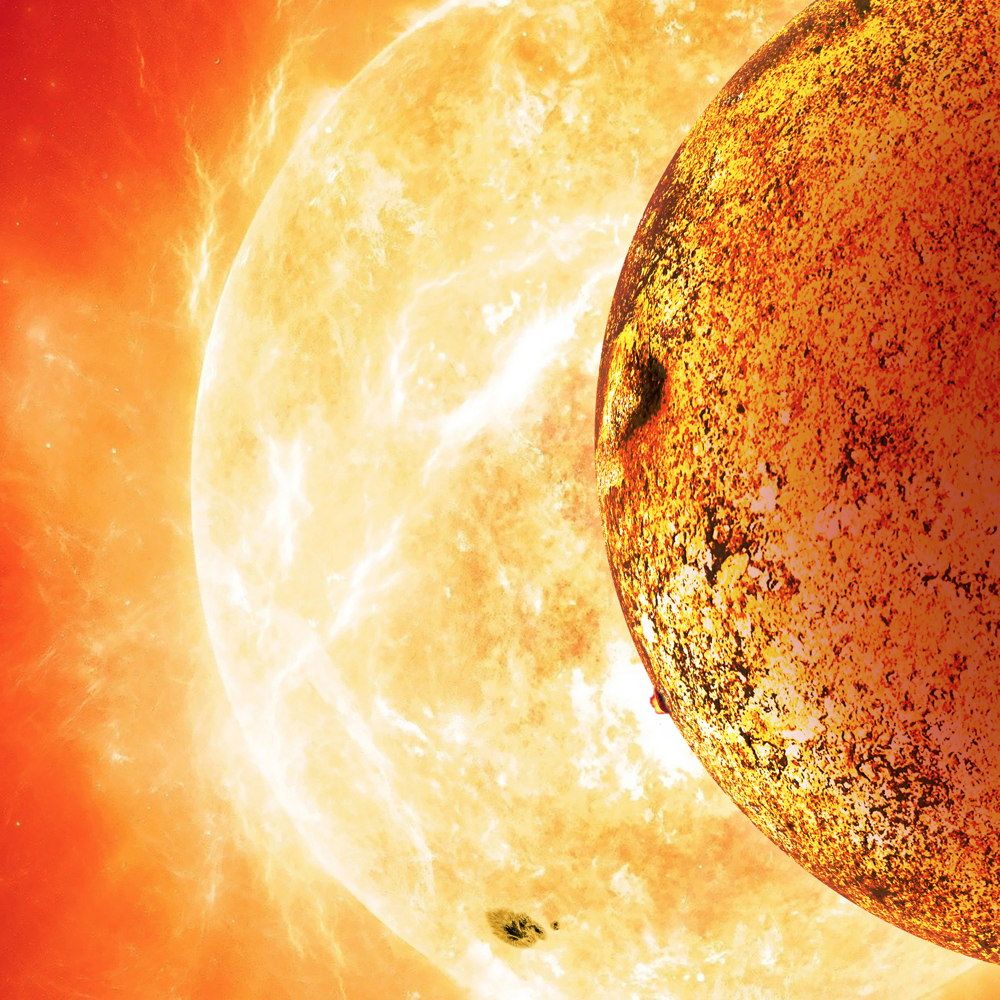

A puzzling alien planet is the closest thing to an Earth twin in size and composition known beyond our solar system, though it's far too hot to support life, scientists say.

The exoplanet Kepler-78b, whose supertight orbit baffles astronomers, is just 20 percent wider and about 80 percent more massive than Earth, with a density nearly identical to that of our planet, two research teams report in separate papers published online today (Oct. 30) in the journal Nature.

"This is the planet that, in many respects, is the most like Earth that's been discovered outside our solar system," said Andrew Howard, of the University of Hawaii at Manoa's Institute for Astronomy and lead author of one of the studies. "It has approximately the same size. It has the same density, which means it's made out of the same stuff as Earth, in all likelihood." [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

Studying a lava world

Kepler-78b, whose discovery was announced last month, orbits a sunlike star in the constellation Cygnus, about 400 light-years from Earth.

The alien world circles 900,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) or so from its parent star — just 1 percent of the distance between Earth and the sun— and completes one lap every 8.5 hours. Surface temperatures on Kepler-78b likely top 3,680 degrees Fahrenheit (2,000 degrees Celsius), Howard said.

The planet was found by NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope, which has spotted nearly 3,600 potential exoplanets since its March 2009 launch. (Kepler was hobbled in May of this year when the second of its orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed, but scientists are still sifting through the instrument's huge databases.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kepler flagged alien worlds by noting the telltale brightness dips they caused when passing in front of, or transiting, their parent stars from the spacecraft's perspective. Kepler's measurements allow researchers to estimate an exoplanet's size but not its mass, meaning that other strategies are required to get a handle on a world's density and composition. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

One such method is the radial velocity technique, which measures the wobble in a host star's light induced by the gravitational pull of an orbiting planet. Both new studies employed this method to investigate the Kepler-78 system, with Howard's group using the HIRES spectrograph at Hawaii's Keck Observatory and another team, led by Francesco Pepe of the University of Geneva, relying on the new HARPS-N instrument on the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands.

The two teams came to very similar conclusions. Howard's group determined Kepler-78b's mass to be 1.69 times greater than that of Earth, while Pepe's team calculated it to be 1.86 times higher than Earth's. The results of the Pepe-led study suggest a density of 5.57 grams per cubic centimeter for Kepler-78b, while those of Howard's team imply a density of 5.3 grams per cubic cm.

These numbers agree to within the error range independently estimated by both teams, suggesting that they are quite accurate, Howard said.

"The fact that we agree to within our errors — in science, that's basically as good as you can do," Howard told SPACE.com.

Earth's density is about 5.5 grams per cubic cm, so Kepler-78b probably has an Earth-like composition, complete with a rocky interior and an iron core, both studies suggest.

A mysterious origin

The extremely tight orbit of Kepler-78b puzzles astronomers. According to prevailing theory, the alien world shouldn't exist where it does, because its host star was significantly larger when the planet was taking shape.

"It couldn't have formed in place because you can't form a planet inside a star," Dimitar Sasselov, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a member of the Pepe-led team, said in a statement. "It couldn't have formed further out and migrated inward, because it would have migrated all the way into the star. This planet is an enigma."

What is clear, however, is that Kepler-78b's days are numbered. The planet will continue circling lower and lower until the immense gravity of its host star tears it apart, likely within 3 billion years or so.

"Kepler-78b is going to end up in the star very soon, astronomically speaking," Sasselov said.

The search for another Earth

The hellishly hot Kepler-78b is not a good place to hunt for alien life. But the determination of its density marks a milestone in the ongoing search for a true "Earth twin" — a planet very much like Earth in size, composition and surface temperature.

"The existence of Kepler-78b shows that, at the very least, extrasolar planets of Earth-like composition are not rare," astronomer Drake Deming, of the University of Maryland, writes in an accompanying commentary article today in the same issue of Nature.

Deming points to NASA's upcoming Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite mission, or TESS, which is slated to launch in 2017 to hunt for transiting planets around nearby stars (as contrasted with Kepler, whose gaze was more distant).

"By focusing particularly on small stars cooler than the sun, TESS should find exo-Earths whose mass can be measured by trading the close-in orbit of Kepler-78b for more distant orbits around low-mass stars, approaching orbital zones where life is possible," Deming writes. "That trade-off probably cannot be pushed to the point of measuring an Earth twin orbiting once per year around a sun twin, but it will allow future scientific teams to probe habitable planets orbiting small stars."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.