Full Belly Fossil! 'Sea Monster' Had 3 Others in Its Gut

DENVER — The mosasaur, a fearsome marine reptile that stalked the Cretaceous seas, scavenged its own kin, a new fossil find reveals.

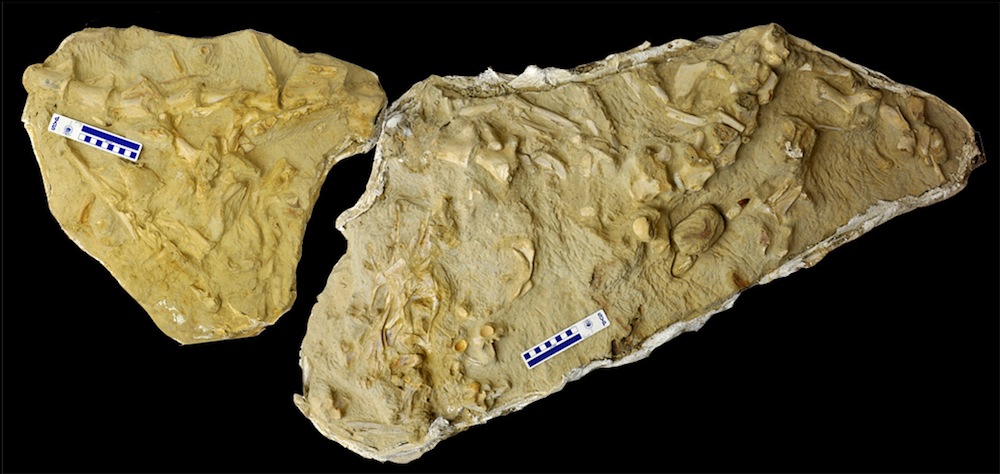

A fossilized mosasaur found in Angola contains the partial remains of three other mosasaurs in its stomach, researchers reported here Tuesday (Oct. 29) at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America.

"These are three different species of mosasaur inside the belly of a fourth species of mosasaur," said study researcher Louis Jacobs, a vertebrate paleontologist at Southern Methodist University in Texas. [T-Rex of the Seas: A Mosasaur Gallery]

The find isn't the first example of mosasaurs digesting mosasaurs, but it illuminates an ancient ecosystem surprisingly similar to ones seen in parts of the ocean today.

A lean, mean, eating machine

Mosasaurs were at the top of the marine food chain from about 98 million years ago to the end of the Cretaceous 66 million years ago, when they went extinct. As is the case for modern whales, the first mosasaur ancestors were land-dwellers. They looked not unlike today's monitor lizards, said study researcher Michael Polcyn, also a vertebrate paleontologist at Southern Methodist University.

"By the time they're in the water maybe 10 million years, they've fully adapted to the marine environment — so a downturned tail with a dorsal fluke and fins — and they were really making their living like a toothed whale," Polcyn told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In other words, mosasaurs were as fearsome predators as today's orcas, but with reptilian, fishlike bodies that could grow to more than 30 feet (9 meters) in length.

A rich ecosystem

The mosasaur with a belly full of other mosasaurs was found at a site called Bentiaba in southern Angola. The fossils are embedded in sandstone cliffs and badlands along the Atlantic coast. During the Cretaceous, this area was just offshore from Africa.

"The incredible richness of the site continues to amaze us," Polcyn said. "Each year we return, there is another significant discovery."

The researchers first discovered the hungry, hungry mosasaur, a species called (Prognathodon kianda), in 2006, but weren't able to excavate it until 2010. That's when they realized the fossil record also recorded the mosasaur's last meal.

The mosasaurs inside the belly are clearly digested, with their tooth enamel eaten away by stomach acid. One is small and eaten whole, but the other two are incomplete, mostly represented by skulls and vertebrae — "not the most nutritious and tasty stuff that you would eat," Jacobs said. The evidence points to the large mosasaur as a scavenger, snacking on the corpses of dead mosasaurs brought to the area by the currents.

The mosasaurs are only part of the story. Paleontologists digging at the site have already uncovered seven mosasaur species, two plesiosaurs, nine sharks and rays, four kinds of turtles and many fish. Virtually all the bones show evidence of scavenging by sharks.

The ecosystem likely owed its richness to the trade winds, prevailing winds that blow between 15 degrees and 30 degrees North and South latitude. At the time, this stretch of coast fell squarely under the influence of these winds, Polcyn said. The winds drive ocean currents that cause upwelling, the circulation of nutrient-rich bottom waters up to the ocean's surface. Such upwelling zones have robust food chains, starting from plankton and ending with large predators. The currents also would have pushed floating carcasses toward shore, Polcyn said.

Rich upwelling zones are common in the oceans today, including a spot off of Monterey, Calif., known for its sea otters and other fauna; a stretch of sea off the Atacama Desert in western South America; and the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem off the coast of Namibia.

The Benguela ecosystem is fueled by the same atmospheric processes that drove the mid-Cretaceous hotspot of life, Polcyn said. The continent of Africa has moved and rotated just slightly over the intervening millions of years, shifting the relative location of the upwelling.

The mosasaur specimen with a full belly is still being prepared by fossil technicians. Researchers have also uncovered other ancient beasts with creatures in their gut at the site, Polcyn said, and they plan to analyze those finds further.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.