Rob Moore is a senior policy analyst for NRDC where he is part of a team devoted to protecting U.S. water resources. Moore contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

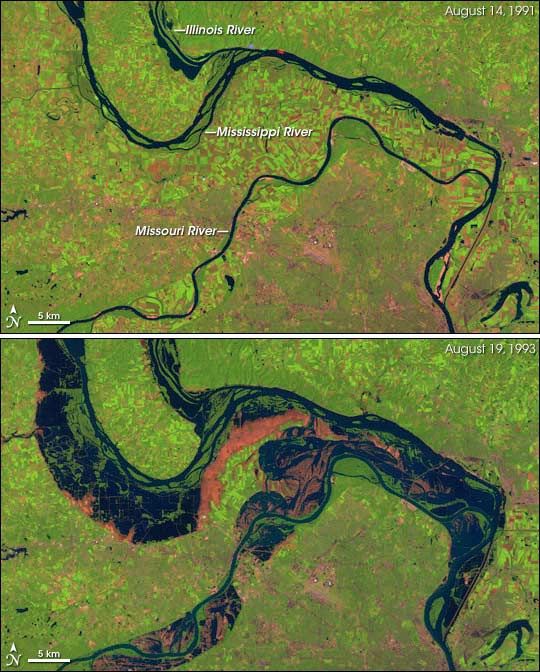

While the nation’s attention is riveted on the one-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, this year marks the 20th anniversary of the record-breaking 1993 flood that inundated homes and farmland across 30,000 square miles of the Mississippi and Missouri River Basins. Some communities were in flood for 200 days.

The massive, 500-year flood inundated parts of the Midwest throughout that summer, and I played a small role in the response while serving in the Illinois National Guard.

Since the Great Flood of 1993, the United States has experienced floods that caused tens of billions of dollars of damages — from the Mississippi River (2002, 2008, 2011); from hurricanes like Katrina (2005), Ike (2008) and Sandy (2012); and from historic flooding this year in Colorado.

The nation has been slow to learn from these devastating natural disasters. But my experiences in the flood twenty years ago left a lasting impression and ultimately led me to the work I now do at NRDC, looking at how climate change is impacting our nation's water resources.

Back then, I was a sergeant in the Illinois National Guard and my unit was activated to respond to flooding along the Mississippi River — we'd seen footage of the flood on television, but I didn't appreciate the enormity of the situation until I set foot on my first levee.

From the levee's base, nothing looked too unusual for a hot, wet July day. Farm fields had standing water in them because of heavy rainfall and it was hot and humid in the blazing sun. But upon reaching the levee's summit I'm sure I muttered something like, "Holy shit."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There was no river. There was an inland sea interrupted by tall trees and the tops of houses and barns. In fact, I was probably quite a distance from the main channel of the Mississippi. But there was plenty of water and it was lapping at the top of the levee I was standing on.

Most of our work that day, and in the days that followed, involved laying sandbags — lots and lots of sandbags. Every day we worked on another levee that was in danger of failing. Some days, we'd work in the hot sun building a wall in anticipation of rising waters. Other days, we'd work in pounding rain, seeing which would rise faster — the river or our wall of sandbags.

There was always an element of danger. A levee can fail suddenly. And the only reason we were working there was because the levees were in danger of failing. Still, there hadn't been many moments when I felt like I was in imminent danger.

In one night, that changed.

After another long day, we had come back to the gymnasium in Hamilton, Ill., where we had been staying. Sometime after dinner, we were told a major levee was at risk of blowing out and everybody was being thrown into the effort.

As soon as we got there, I knew we were in a bad situation. National Guardsman were everywhere, scurrying around. Light sets and vehicle lights lit up the levee. After I parked the deuce-and-a-half that brought me and my squad there, I walked up the levee to get a sense of the situation. A few steps up the slope immediately told me we had a problem. With each step my boot sunk in. When I'd pull it out, water pooled into the void. The levee was saturated.

As unsettling as it is to stand on a levee in the daytime and see the entire landscape flooded, it's far more unsettling in the dark of night when you can't see a thing, especially when the levee your standing on feels like a wet sponge.

We were a pretty good distance from the highway — and higher ground. Dozens of trucks full of guys out there had all come down that same road. When the levee went (not if), it would be impossible to load everybody onto trucks in the dark and drive out on that dirt road while the river poured through a breach behind us.

As that revelation sunk in, somebody yelled to me. "Sgt. Moore, get over here and help get this truck unloaded!" A semi-truck had pulled up loaded with hay bales, or maybe it was straw. "Open these bales up and start spreading them on the levee!"

It wasn't clear what this brilliant idea was supposed to accomplish, but it was obvious it wasn't going to accomplish much, a fact I felt compelled to point out to my superior.

"Keep spreading," I was told.

It was a weird night. Everybody there knew this levee was going to fail, no matter what we did. We just hoped somebody higher up would give the order to pull us out before the inevitable happened.

We were finally told to load up and head home. The next morning we learned the levee failed.

That night opened my eyes to how our nation has dealt with flooding. We've built and re-built levees along our major rivers. Again and again, we've been shown that such defenses will fail. We've provided subsidies for flood insurance that encourage people to live in flood-prone areas. Again and again, taxpayers have picked up the tab to rebuild in the same vulnerable places.

Now, our rapidly warming climate is making the risk of flooding even greater. As sea levels rise, our coastlines are at greater risk from flooding due to inundation and to storm surges. A recent scientific study found that flooding like that experienced by New Yorkers in Hurricane Sandy could happen every year or two, if society doesn't cut emissions deeply and keep the oceans from rising too far too fast.

When I look at what climate change has in store for us, I sometimes feel like I'm back on that shaky levee in the dark of night with the river pressing on it.

Scientists have a clear idea of what's going to happen as the climate warms. Study after study shows that sea levels are going to rise 1 to 2 feet, even with reductions in carbon-dioxide emissions. Sea levels will rise even more if people don't make deeper cuts in greenhouse gas emissions more quickly. We also know that flooding along inland rivers will become more frequent and severe, as storms intensify in response to climatic changes.

Now, we just have to decide how we prepare for the consequences that are already unavoidable.

Moore's most recent Op-Ed was "2012 Weather Extremes Could Become the Norm". The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.