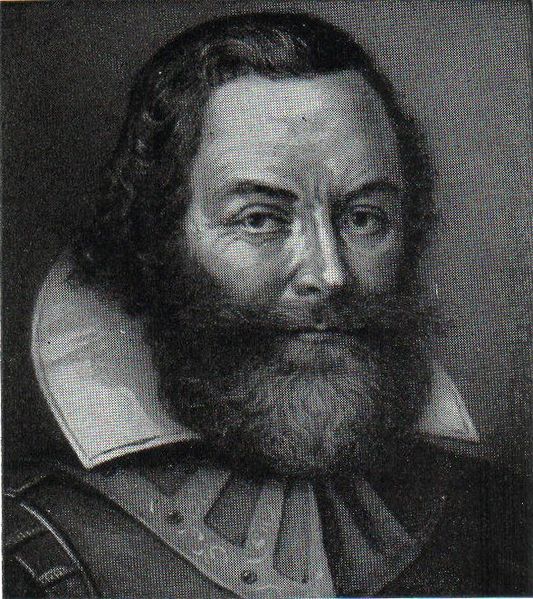

John Smith of Jamestown: Facts & Biography

John Smith was an English explorer, soldier and writer best known for his role in establishing the first permanent English colony in the New World at Jamestown, Virginia. Smith's legend has grown over the centuries, in particular due to the popular story of his involvement with Pocahontas, a native American princess.

However, Smith was a notorious self-promoter, and the truth of that tale may never be known. Much of what is known about Smith comes from his own writings, which include multiple versions of events and enhance Smith’s role. George Percy, a fellow Jamestown leader and eventual governor of Virginia, described Smith as “an Ambityous unworthy and vayneglorious fellowe.” Smith’s self-aggrandizing personality has cast doubt on his claims since the 1600s, and his legacy remains controversial today.

Early years

Smith was born in 1580 to a farming family in Lincolnshire. He left home at age 16 to become a soldier, traveling to France to fight the Spanish. After his return to England, he taught himself wilderness survival techniques, and later worked on a merchant ship. In 1600, he went to Hungary to fight with the Habsburg forces against the Turks, where he was promoted to captain.

In 1602, he was captured and enslaved by a Turk, who sent him to what is now Istanbul to serve his sweetheart. According to Smith, the girl fell in love with him but sent him to serve her brother with hopes that her brother would train him for the Turkish imperial service. The brother, however, was cruel. Smith killed the brother and escaped. After traveling widely in Europe and North Africa, he returned to England in 1605.

Jamestown

Back in England, a restless Smith became involved with the Virginia Company, which sought to colonize Virginia. On Dec. 20, 1606, three small ships carrying 104 settlers, including Smith, left England, bound for Virginia. During the trip, Smith was arrested for mutiny.

According to Smith, the gentlemen on board were jealous of his military and naval experience and looked down on him because of his rural upbringing. He said they accused him of plotting to seize power for himself. He spent most of the voyage in irons and was nearly hanged.

Prior to departure, the leaders of the Virginia Company had selected seven voyagers to govern the colony. They put the names of the chosen in a sealed box, which was not to be opened until arrival in Virginia. Upon landfall four months later, the colonists opened the box and discovered that Smith’s name was among the chosen leaders. Smith was allowed to take up a position on the council — but he remained disliked.

Early on, Jamestown was plagued by several problems: drought, harsh winters, swamps, famine, thirst, disease and skirmishes with the natives. Smith’s approach to these problems differed from many of the council members. Smith regarded the other leaders as gentlemen with no knowledge or experience in how to fight for survival. After five months in Jamestown, Smith and two other councilmen came together to remove colony president Edward Wingfield from office. John Ratcliffe was assigned to be the new president.

Under Ratcliffe’s leadership, Smith was appointed cape merchant and tasked with trading with the natives for food. Smith conducted expeditions throughout the region.

Chief Powhatan and Pocahontas

On one such expedition in December 1607, Smith and his party were ambushed on the Chickahominy River by a large Powhatan hunting party. Smith was the sole survivor and was brought to Werowocomoco, the village of the paramount chief’s residence.

What happened next is unclear, as Smith gave varying accounts, and the story has been mythologized in popular culture. The popular story is that the natives were ready to bash his brains out, when Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan’s 11-year-old daughter, threw herself on top of Smith, trying to shield him from death. However, Smith did not write this version until 1624 in his book, "Generall Historie."

In a letter written soon after the event and long before "Generall Historie" was published, Smith described feasting and conversing with Chief Powhatan. Most historians believe that the Powhatan people conducted an adoption ceremony, welcoming Smith into their community, but that Smith did not understand this. Also, anthropologist Helen C. Rountree points out in "Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Lives Changed by Jamestown" (2005) that Pocahontas may well have been too young to even attend the ceremony. Girls her age were responsible for preparing food and cleaning up afterward.

Chief Powhatan announced that they were friends and that if Smith gave him two cannons and a grindstone, he would give Smith the village of Capahosic and would consider him a son. It is now understood that Chief Powhatan was trying to expand his empire and neutralize the English threat, but Smith may not have seen this motivation.

After four weeks at Werowocomoco, Smith returned to Jamestown on friendly terms with the Powhatan people. They continued contact for some time, and Pocahontas often visited Jamestown with food. Though she and Smith were acquainted, they were never romantically involved.

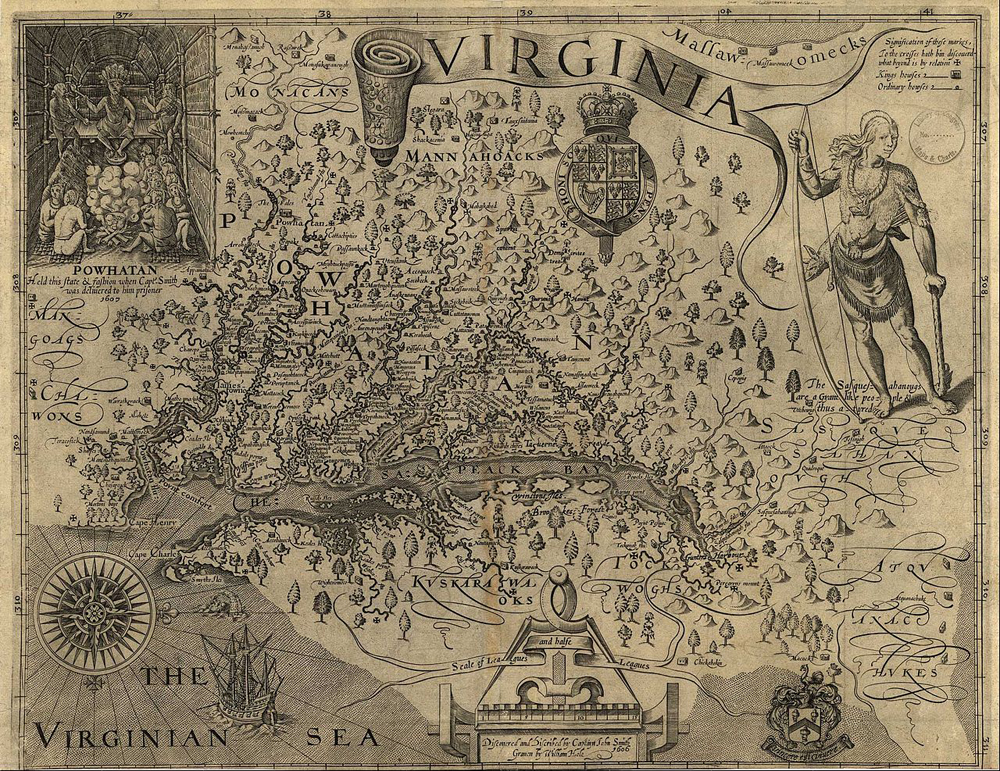

Mapping the Chesapeake

When Smith returned to Jamestown in January, he discovered that he had been replaced on the council. Settlers thought Smith was responsible for his companions’ deaths on the Chickahominy River, and he was sentenced to hang. Luckily for Smith, the night of his sentencing, about 100 new settlers from England arrived with food and other reinforcements. Smith’s charges and execution were forgotten during the celebration.

With the arrival of new settlers and the help from the Powhatans, the situation at Jamestown began to slowly improve. At this point, the Virginia Company sent Smith to explore the Chesapeake in search of gold and a passage to the Pacific Ocean. Smith embarked on two lengthy voyages, investigating 2,500 miles of territory. He did not find gold or a route west, but he did acquire food for the colonists, learned about the natives and created highly accurate maps of the area. These maps became one of Smith’s greatest accomplishments and were used by future explorers.

Presidency and war

When he returned to Jamestown, Smith’s popularity once again plummeted. A private letter he had written detailing his dissatisfaction with colony leadership and Virginia Company policies had been published in England. Company and colony leadership was understandably displeased.

Nevertheless, in September 1608, Smith was elected president of the colony. He immediately set about strengthening defenses and securing more food. Smith declared, “He that will not work shall not eat,” and forced the colonists to plant crops, repair the fort, develop products like pitch and soap ash for export, and more. According to Smith, his policies yielded productive results — but they nevertheless remained unpopular. The death toll fell but colonists were still unable to produce enough food and remained dependent upon Indian trade.

This was problematic because Virginia was experiencing a severe drought. The Powhatan community was also short on food, and therefore refused to share with the English for a time. Smith responded to this situation with violence, burning villages, stealing food, imprisoning, beating, and forcing the natives into labor. This violent approach caused further problems for Smith, since Virginia Company officials and other colony leaders wanted to convert the Indians to Christianity.

In 1609, the colonists decided to “coronate” Chief Powhatan in an attempt to improve relations with the natives while putting them under King James’ rule. Smith warned that this wouldn’t work, and he was right. Powhatan refused to kneel and the ceremony was a failure. Powhatan cut off aid to the settlers and tried to have Smith killed. Some versions of the story attest that Pocahontas warned Smith of the murder plot.

Relations between the English and the Powhatans were ruined, and the First Anglo-Powhatan War began. It ended only when Pocahontas married John Rolfe in 1614. Smith continued to have political troubles, enacting controversial policies and refusing to step down as president. The Virginia Company decided instead to do away with the title and send a governor.

In September 1609, Smith was caught in a gunpowder explosion and suffered severe burns. Though Smith claimed that the explosion was an accident, historians think it may well have been attempted murder. The severely injured Smith was sent back to England. After he left, Jamestown experienced a terrible famine known as the Starving Time, which only 60 out of 240 settlers survived.

Later years

Despite his wishes, the Virginia Company did not send Smith back to Jamestown, and he never again returned to the colony. He did, however, explore and map an area north of Virginia, which he named New England. His efforts to establish a colony in New England were thwarted when he was captured by French pirates in 1615. After his escape, Smith returned to England and began writing about his life.

In 1620, the Pilgrims almost selected Smith as their military adviser but they chose Miles Standish instead. They did, however, use Smith's map of New England when voyaging to Plymouth.

Smith reunited with Pocahontas in England, when she traveled there with John Rolfe and their son. Smith continued to write his memoirs and offer advice until his death on June 21, 1631.

Further reading

- Historic Jamestowne, Preservation Virginia

- Life of John Smith, National Park Service

- Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend, National Park Service

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.