Bugs in Patagonia Survived Dinosaur-Killing Impact

There may be some truth to the old joke about only insects surviving an apocalypse.

Down in Patagonia, thousands of miles from the site of the deadly asteroid impact in present-day Mexico that killed off the dinosaurs, most bugs easily survived one of Earth's worst mass extinctions 65 million years ago. The discovery adds to a growing body of evidence that the Cretaceous mass extinction had varied effects on species in different spots around the world.

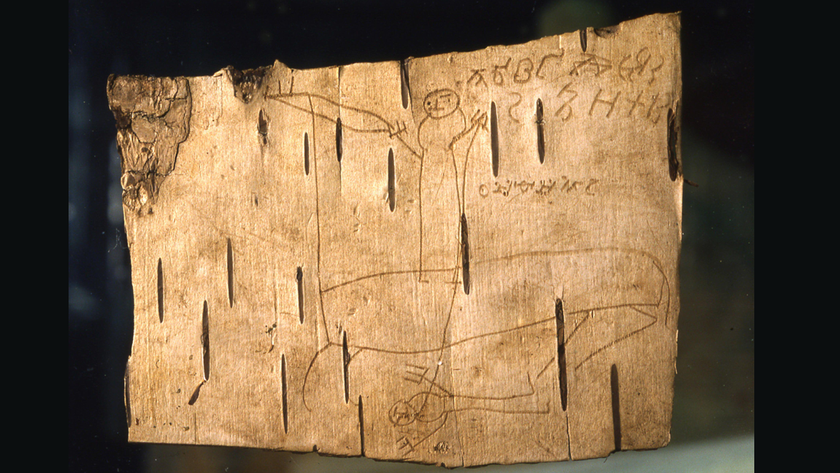

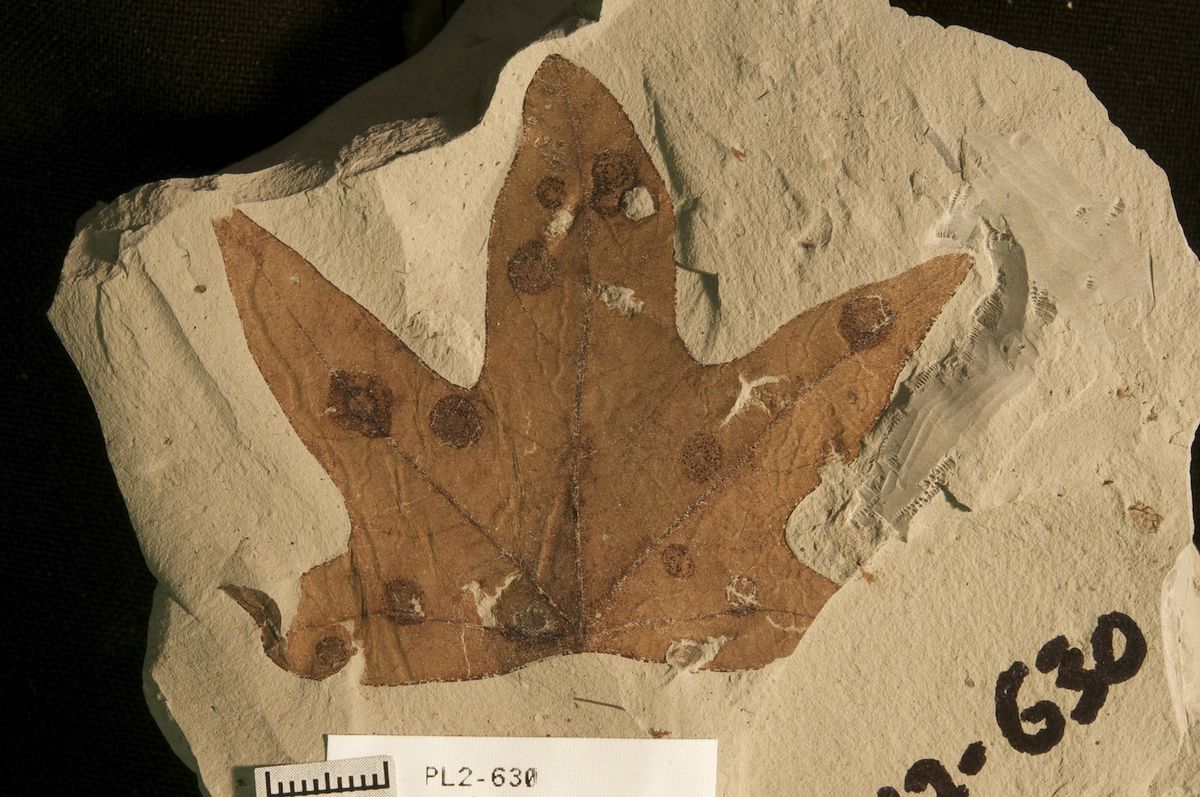

Evidence from fossilized leaves suggests that, compared with insects in North America, a greater diversity of insects in South America chewed, sucked and otherwise fed off plants after the Cretaceous extinction, researchers reported Oct. 28 at the Geological Society of America's annual meeting in Denver.

"There were devastating effects everywhere ... the dinosaurs did go extinct on every continent, obviously," said Michael Donovan, a graduate student at Pennsylvania State University. "Our results suggest the Southern extinction was different than what was seen in the North. It supports the emerging hypothesis of an early Paleocene refugium."

On both continents, insects from just before and after the Cretaceous-Paleocene extinction are rarely preserved as fossils, Donovan said. But there are thousands of leaf fossils and damage from insects, each of which ate in a unique way, which serve as a substitute for tracking species.

To track the extinction's effects on South American insects, Donovan has pored over about 3,000 leaf fossils from the Lefipán and Salamanca Formations in Argentina. The Salamanca rocks were deposited at about 50 degrees South latitude, during the Paleocene epoch.

The evidence suggests that before the impact, there was more diversity among bugs such as leaf miners, beetles, moths and flies in South America than in North America. After the mass extinction, both continents saw a decrease in diversity among bug species, but the drop was less severe in Patagonia, Donovan said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The overall decrease in leaf damage types varied from 9 to 25 percent in Patagonia to 35 to 45 percent in fossils from the Western Interior Seaway, the great inland sea that once flooded western North America.

Among highly specialized insects, which chow down on only one or two kinds of plants, the die-offs were more severe closer to the impact site. There was only a 21 to 34 percent drop in leaf damage in Patagonia versus a 55 to 75 percent decrease in North America, Donovan said.

Pollen studies show a severe die-off in North American plants immediately after the impact. But pollen records confirm that the Patagonia insects' food source bounced back quickly after the asteroid hit Earth, according to a study published Dec. 17, 2012, in the journal PLOS ONE. Ocean plankton in the Southern Hemisphere also survived.

"The insects were highly affected by what the asteroid did to their food," said Peter Wilf, a paleobotanist at Penn State and a co-author on both studies.

"The end Cretaceous extinction really does seem to be different than the story in North America," Wilf said. "There seems to be much less of an extinction, and the recovery seems to be much faster."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.