To Cut Carbon, a Decade is Too Long to Wait (Op-Ed)

Jeffrey Rissman, policy analyst at Energy Innovation: Policy and Technology, contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

While there is a global consensus to cut greenhouse gasses, many approaches look to solve the crisis over decades — but, there are critical reasons that even ten years is too long to wait.

First, delaying action allows natural carbon-dioxide (CO2) feedback loops — climate-altering processes that accelerate as more CO2 enters the atmosphere — to gather strength. For example, warmer oceans remove less CO2 from the atmosphere than cooler oceans, and they have even become net CO2 emitters during warming periods in the Earth's past; wildfires and desertification release carbon stored in vegetation; and melting permafrost allows for the decomposition of peat bogs and the melting of methane hydrates, releasing methane into the atmosphere. At some point, such feedbacks may become sufficient to perpetuate warming even in the absence of human-caused emissions. If society waits a decade to curb greenhouse gasses, such effects will be far stronger than they are today. That will require humans to undertake much more drastic emissions cuts, at considerably higher cost, than if nations took strong action to cut emissions now.

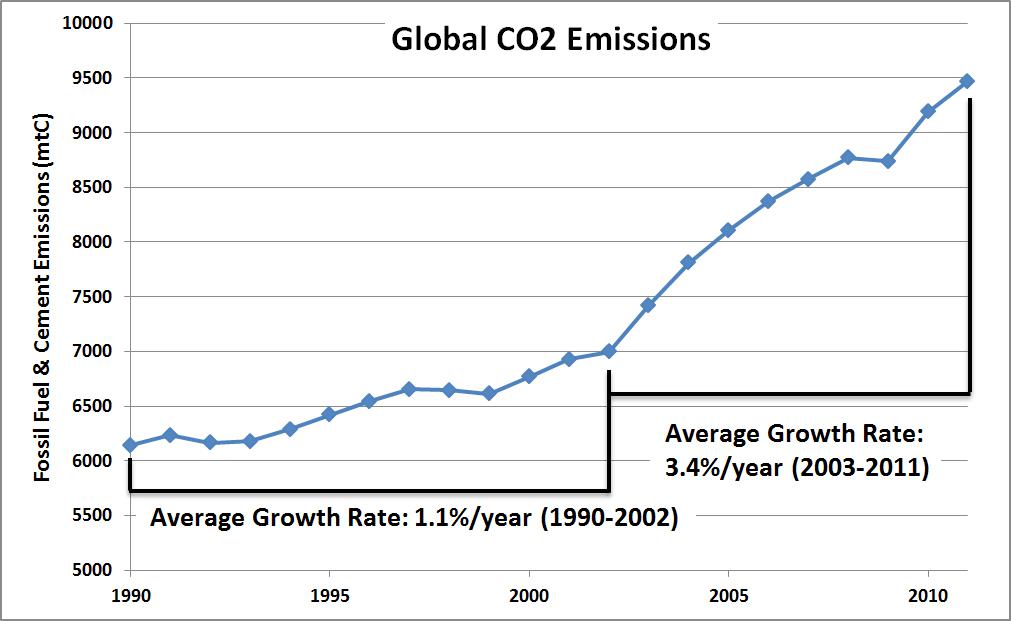

Second, since 2003, global emissions have been increasing at more than 3 percent per year, driven in large part by the industrialization of developing nations such as China and India. As their populations climb into the middle class and move from the countryside to the cities, they demand energy-using technologies, such as lighting, appliances, cars and electronics. In order to accommodate the new consumers, developing countries are rapidly constructing new buildings, roads and power plants. From 2009-2025, China will add 350 million people to its cities, build 5 million buildings (including 50,000 skyscrapers, the equivalent of ten New York Cities), and pave 50 billion square feet (5 billion square meters) of road. This long-lasting infrastructure will set patterns for how energy is used for decades to come. Now, not ten years from now, is the critical time for those countries to adopt policies that will ensure the construction of efficient buildings; compact, transit-oriented cities; and renewable energy-generation facilities.

Third, in the U.S., greenhouse-gas emissions have recently declined from their peak in 2007. This was first due to the global recession and then to the shale-gas boom, which led to cheap natural gas that has reduced coal consumption (which emits more CO2 than natural gas) and made new coal plants uneconomical. Society cannot rely on either of those factors continuing to bring emissions down. The U.S. economy is already recovering, the country is rapidly building export capacity for natural gas (which will help to bring domestic U.S. prices in line with prices on the world market, increasing the competitiveness of coal), and there will be fewer and fewer remaining coal-power plants to replace with gas. Additionally, the amount of methane leakage from natural gas facilities remains highly uncertain.

Methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2. Depending on the leakage rate, moving from coal to natural gas could fail to provide any climate benefits for 50 or even 100 years. The U.S. must make a serious commitment to zero-carbon energy and energy efficiency in the next ten years in order to be able to reduce emissions to the level required to stabilize atmospheric CO2 concentrations in a reasonable timeframe.

Finally, some critics of immediate action to reduce greenhouse gasses point out that technological innovation will bring down the costs of clean energy and open up new options in the future, so society should wait until clean-energy costs are lower before making a serious commitment to deployment. However, in the energy sector, innovation is fundamentally tied to deployment. Companies decide what research to pursue on the basis of what they believe they will be able to market and sell — they learn how to efficiently manufacture technologies and drive down costs through the process of producing and deploying their technologies at scale. And if nations wait to address greenhouse gasses, there will be a larger amount of high-carbon infrastructure to replace, increasing future costs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Society cannot sit back and wait for innovation to bring down costs before taking action. We must begin deployment now, and that deployment will itself be an important driver of innovation, which will result in better and cheaper options in the future.

Scientist and lead Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change author Keywan Raihi and colleagues found that delaying action just seven years — from 2013 to 2020, as agreed at the 2012 Doha U.N. climate summit — will increase by $5 trillion the cost of staying below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) of warming. Put in terms of a global carbon price, a tax implemented today could be just $20 per ton (18 cents per gallon of gasoline), while a delay to 2020 would increase the cost to $100 per ton (89 cents per gallon of gasoline).

It is vastly better for human welfare, for economic prosperity, and for the environment if nations begin strong measures to reduce emissions today.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.