Food-Borne Tropical Disease Outbreak Strikes the US (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

A food-borne illness is spreading quickly through the United States, an investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has revealed. The disease, called cyclosporiasis, is common to tropical and subtropical regions. While occasional outbreaks have been recorded since early 1990s in the US, the current spread of the disease has been swift and wide.

Three small outbreaks of cyclosporiasis were reported in North America during 1990-95, and major outbreaks have been recorded since 1996. The disease made its way through fresh produce of raspberries, lettuce, basil and snow peas, which were mostly imported from countries where the disease is endemic. Cyclosporiasis has been found in Ghana, Peru, Guatemala, Egypt, Turkey, Nepal and Haiti.

More than 1100 sporadic cases of confirmed cyclosporiasis occurred during 1997-2008, involving 12 US states. About a third of these were thought to have been associated with international travel to endemic regions.

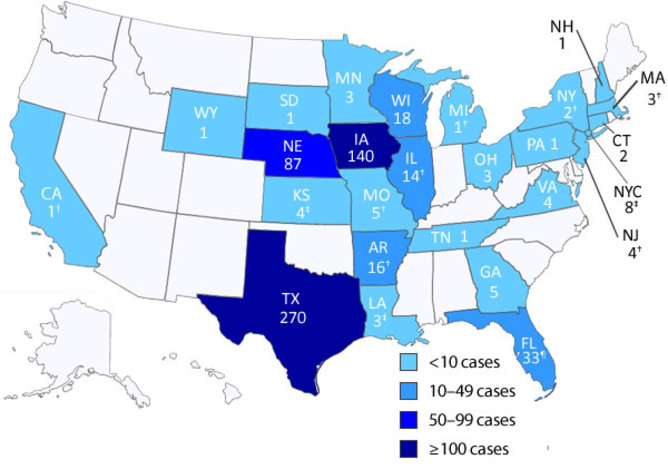

So far 2013 has seen the biggest outbreak. From June to August this year, an unusually large number of cyclosporiasis reports were recorded by the CDC, involving more than 600 individuals from 25 states, with high numbers in Texas, Iowa, and Nebraska.

Investigations by health officials revealed the possibility of two outbreaks. Cases in Iowa and Nebraska were associated with restaurants, and involved a salad mix (iceberg and romaine lettuce, red cabbage, carrots) sourced from the Mexican processing facility of a group of farms. Cases in Texas were associated with uncooked coriander sourced from Puebla, Mexico.

Human cyclosporiasis is a disease caused by the single-celled parasite Cyclospora cayetanensis. Although there are about 18 different species of Cyclospora currently known, four appear to be specific to non-human primates. Only Cyclospora cayetanensis has been discovered in humans. Attempts to create non-human animal models of C. cayetanensis infection have been unsuccessful, suggesting host-specificity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

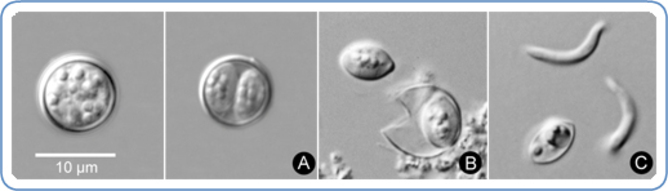

The transmission of this parasite occurs via what is referred to as the “fecal-oral route”. In excreted fecal matter, Cyclospora exists in the form of oocysts (a thick-walled structure containing immature, dormant parasite spores), a product of sexual reproduction of the parasite. These are not infectious, but are highly resistant to common disinfectants used in food-processing industries.

Within two weeks, the spores mature – making the oocysts infectious. Neither the natural environments of this process, nor the exact manner of transmission, are yet known, but contamination of water and food (such as raw produce) with oocyst-containing fecal matter likely contributes to the dissemination. Risks of infection increases via the common factors – consumption of untreated food or water, lack of adequate sanitation and the presence of animals in the house.

This parasite primarily targets the small intestines. An infection often causes gastro-intestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal cramping, loss of appetite, and bloating. The infected may also suffer from nausea, fatigue, weight-loss and sometimes fever. In absence of proper treatment, some of these symptoms may continue for weeks, while some may be temporarily relieved, only to recur.

The good news is that the infection is not generally life-threatening and people with healthy immune systems may not require treatment. However, in children and in the elderly, as well in individuals with weak immunity (such as AIDS or cancer patients), untreated cyclosporiasis may cause severe, and occasionally fatal, illness.

Currently the drug of choice for Cyclospora infection is Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. According to the CDC, proper storage, washing and cooking of fresh vegetables and fruits should keep the disease in check.

All viewpoints expressed in the article are those of Kausik, and do not necessarily represent official positions of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions and the Johns Hopkins University.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.