Everyone Agreed: Cane Toads Would Be a Winner for Australia (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

When cane toads were released in Australia in 1935, they were the latest innovation in pest control, backed by a level of consensus support that a scientist could only dream of. So what went wrong?

Research published today reveals previously unreported government documents supporting the release of cane toads in Australia.

Cane toads built on successes in biological control, replaced pesticides like arsenic, pitch and copper, were supported by a published scientific paper, had international scientific peer review, were endorsed by Australia’s peak science body CSIR, championed by industry, promoted by the Queensland government and its premier, met quarantine regulations, were approved by the Commonwealth government and endorsed by the prime minister.

With cane toads, Australia thought it was on to a winner.

Today, a toxic cane toad slick rims northern Australia. The history of how that happened is important – especially if we’re to avoid making similar mistakes again.

Modern insecticides were developed in the 1940s. Before then, farmers and gardeners used predatory and parasitic wasps and flies, insect-eating birds, mongoose and toads to tackle pests. In the late 19th century, the US Department of Agriculture elevated biological control to a science. Common practice was to release exotic agents of biological control untested into new environments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

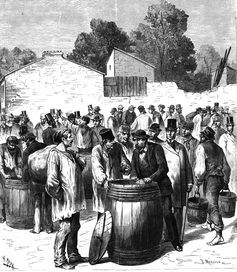

Toads had a pedigree. In 19th century France, toads were sold to gardeners at markets in Paris. French cane farmers carried giant toads from South America to control pests in their Caribbean sugar plantations.

In the early 20th century sugar cane scientists carried cane toads from Jamaica and Barbados to Puerto Rico, from there to Hawaii and then Queensland and Pacific Islands to control sugar cane pests.

The target pest for cane toads were species of scarab beetles whose larvae, grubs, browsed roots of sugar cane. The fatally flawed plan was that earthbound toads would control soil-dwelling grubs by somehow managing to eat airborne adults.

In Australia, biological control did have a precedent. The highly successful control of exotic prickly-pear cactus by the introduced Argentinian moth Cactoblastis cactorum in 1926 added to the consensus that biological control was the answer to the sugar industry’s woes.

There were few opponents to the introduction of the toad in Australia, and only one made his views public: retired former New South Wales Chief Entomologist Walter Froggatt. He forecast that cane toads

may become as great a pest as the rabbit or [Prickly-pear] cactus.

But Frogatt’s peers rebuked him. Eminent scientists branded his views “decidedly pessimistic”, “radical and biologically impossible apprehensions”, and accused him of holding “an incurable bias”. Today, some might label him a toad “denier”.

In 1935, Queensland government entomologist Reg Mungomery carried cane toads from Hawaii and released them in northern Queensland. During the 1930s, cane toads were distributed throughout the Pacific Islands; many came from Hawaii and some from Queensland.

With the help of man, cane toads colonised some 138 territories and they now rank among the world’s most invasive species.

But the full extent of that impact in Australia only became obvious generations later. In 1975, 40 years after the toad’s release, the first survey of the awful impact of cane toads on Australian fauna was published by Mike Archer and Jeanette Covacevich of the Queensland Museum. And after 60 years, CSIRO first studied their interactions with northern Australian fauna.

More recently, Rick Shine, leader of Sydney University’s Team Bufo concluded that although their impact has been profound it is sometimes hard to separate from natural background variations of little known ecosystems.

Well-trained scientists from prestigious institutions helped spread the cane toad. By the criteria of the times, they were far from incompetent. It is simply wrong to think that current generations are qualitatively different and that such a calamitous biological event could not be repeated.

The catalyst was the consensus that restricted free enquiry. It led to oversimplification and misinformation. It prevented questioning of the suitability of cane toads.

Information was to hand in the observations of Queensland’s own scientists, but it was ignored. And there was no understanding of the toxicity that became the main problem for native fauna trying to eat cane toads.

Some would argue that consensus among scientists is an unnatural state for minds programmed to question sacred orthodoxies. But one thing is certain: we should be opening the doors of consensus to scientific scrutiny and critical debate, no matter what the issue, if we are to learn anything from the well-intentioned devastation wrought by the cane toad.

Nigel Turvey does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.