Catholic schools don't provide a better education than public schools, at least when it comes to basics like math and reading, new research suggests.

Children at Catholic schools don't improve their math or reading scores on standardized tests across elementary school and don't show better behavioral outcomes than public school children, according to the study, which will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Urban Economics.

"Across many outcomes, both academic and behavioral, we don't find anything that seems to point to a real benefit of Catholic schools over public schools," study co-author Todd Elder, an economist at Michigan State University, said in a statement.

Early edge

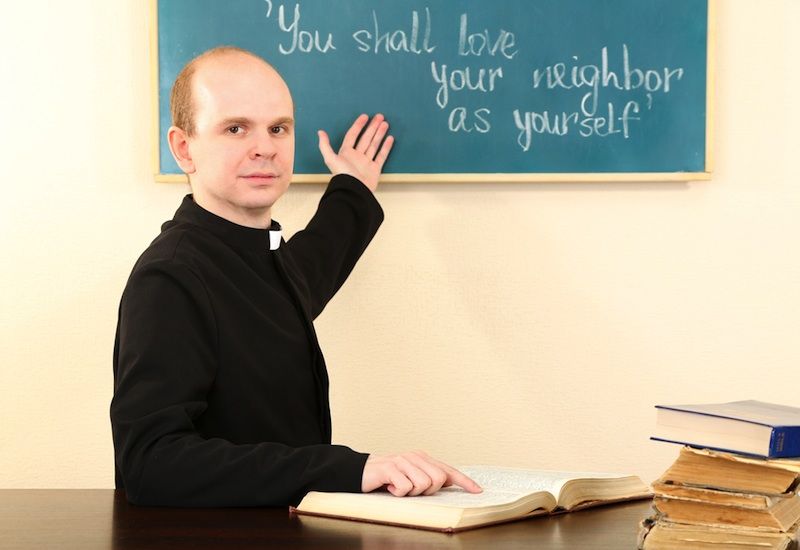

Many an adult remembers sitting through classes taught by Catholic priests and nuns, and more than 2 million children are currently enrolled in one of 6,700 Catholic schools across the country, according to the National Catholic Educational Association.

Past research found that Catholic school children outperformed their public school peers in reading and math, making it seem on the surface that parochial education was a better bet. But those studies didn't track children from the very beginning of their educations. [Science Education: Top and Bottom States]

Elder and his colleague Christopher Jepsen, an economist at University College Dublin in Ireland, analyzed the test results of more than 7,000 students who participated in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study: Kindergarten Class of 1998-99. The children were followed in kindergarten, first grade, third grade, fifth grade and eighth grade.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The standardized test data revealed that Catholic school kids' edge starts at the very beginning, when the youngsters are just a few weeks into kindergarten.

"What you see is that the kids who go to Catholic schools are much, much different the day they walk in the door than the kids who go to public schools," possibly because they come from a higher socioeconomic background, Elder said.

No gains

But the Catholic school participants didn't improve their scores over time. For instance, the average math scores of the Catholic schoolchildren fell from 62 percent in kindergarten to 57 percent in eighth grade. During the same period, average math scores for children in public schools rose from 47 percent to 49 percent. Reading scores were virtually identical.

"There is no difference in reading scores between Catholic school students and public school students once we account for differences in family background and other factors — 1 percentile point at most," Jepsen told LiveScience.

And behavioral outcomes weren't significantly different either: Catholic school children had roughly one day fewer of absence but one more tardy than public school children in fifth grade. Catholic schoolchildren were only 5 percent less likely to have been suspended in eighth grade, and both types of schools have similar rates of grade-repetition, Jepsen said.

Elder speculates that Catholic schools pay their teachers less and thus may attract poorer teachers — Catholic schoolteachers nationally earned an average of $35,730 compared with an average of $51,660 for public school teachers

Another possibility is that public schools have a better curriculum.

Of course, many parents don't send their children to parochial schools for superior education. Instead, they want their children to get religious or moral instruction, which the new study didn't measure, Jepsen said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.