In Photos: The Power of Poison Through Time

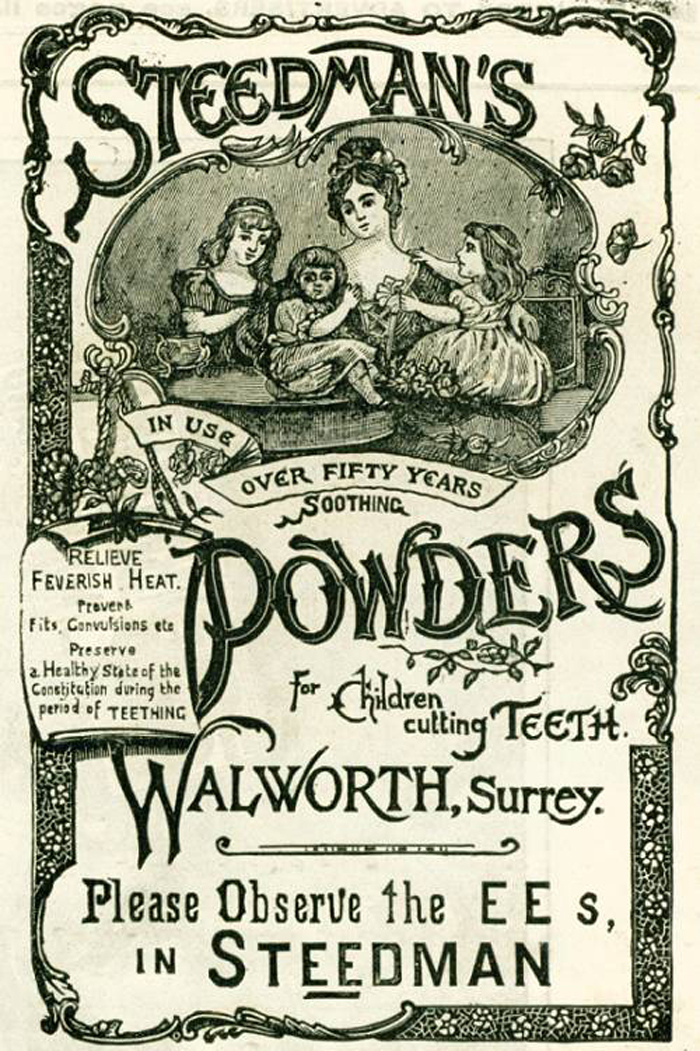

Steedman's Powders

Although mercury is highly toxic, various forms of it have been used medicinally for thousands of years, even into the mid-20th century. Mercurous chloride, known as calomel, was used to treat a variety of maladies, including yellow fever. In the 1860s, calomel pills containing mercury were popular for conditions ranging from constipation to depression. Mercury was even used in teething powder until 1948, when it was banned for making children sick. The element mercury, along with other subjects, will be explored in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Mercury

In its pure form, mercury is a shimmering liquid even at room temperature. Liquid mercury is hard for the body to absorb, making it less toxic than other forms. But it gives off toxic vapors that enter the body easily. When mercury combines with other chemicals, it is much more dangerous. Mercury forms countless chemical compounds, most of them toxic. Touching a single drop of dimethyl mercury, for instance, is fatal, with no known antidote or cure. The element mercury, along with other subjects, will be explored in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

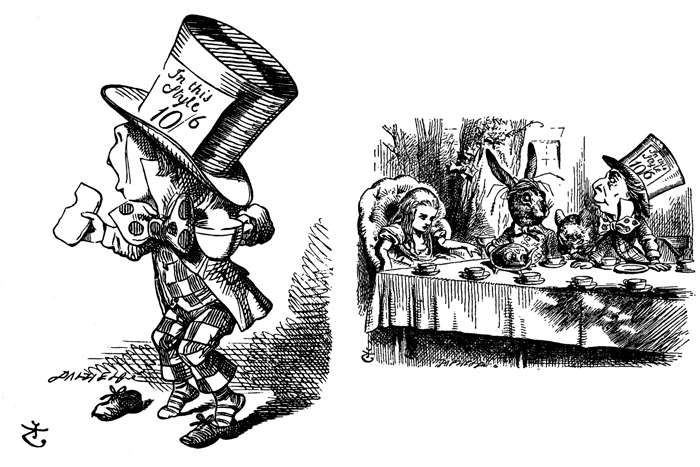

Mad Hatter

The exhibition will include a life-sized scene of the Mad Hatter from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. The saying “mad as a hatter” dates back to the 19th century, when mercuric nitrate was used in the millinery industry to turn fur into felt. Hatters working in poorly ventilated factories breathed in toxic fumes, and prolonged exposure led to mercury poisoning with symptoms—such as trembling, memory loss, depression, irritability, and anxiety—that are still described as “mad hatter’s disease.” This, along with other stories, will be explored in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Golden Poison Frog (Phyllobates terribilis)

The skin of Phyllobates terribilis, a frog first described by Museum herpetologist Charles Myers in 1978, is, ounce for ounce, one of the most toxic substances on Earth. Live golden poison frogs will be on display in the exhibition’s walkthrough diorama of Colombia’s Chocó rain forest. The toxicity of golden poison frogs, along with other subjects, will be explored in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Blowgun darts, quiver, and fiber containers

These darts, collected in the 1930s, would have been coated by hunters with a powerful plant-based toxin known as curare. Fine plant fiber wound around the darts’ ends ensures a snug fit in the blowgun tube and gives the hunter’s breath a surface to push against. The round containers, another product of the palm tree, hold extra fiber. These darts, along with other artifacts, will be on view in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Curare pot

“Curare” is the general term for a variety of toxic substances, made from the roots, bark, stems, and leaves of any of several tropical trees, vines, and plants; it has traditionally has been used to coat blowgun darts. To make the poison, the plant material is boiled for hours in large pots. The liquid is then strained. When it thickens, the resulting paste is stored in various types of containers, including clay pots like this one. This pot, along with other artifacts, will be on view in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake skull (Crotalus adamanteus)

Of the thousands of known snake species, only a few hundred wield venoms powerful enough to harm humans. A snake’s venom might include neurotoxins that immobilize or weaken prey, making them easier to subdue, or even enzymes that begin digesting prey before it is ingested. Snakes also deploy venom against predators. The Eastern diamondback rattlesnake is a venomous pit viper, a group that includes snakes that evolved powerful toxins to defend themselves against opossums. This rattlesnake skull, along with other objects, will be on view in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Beaver felt top hat

The saying “mad as a hatter” dates back to the 19th century, when mercuric nitrate was used in the millinery industry to turn fur into felt. Hatters working in poorly ventilated factories breathed in toxic fumes, and prolonged exposure led to mercury poisoning with symptoms—such as trembling, memory loss, depression, irritability, and anxiety—that are still described as “mad hatter disease.” This, along with other historic uses of toxic materials, will be explored in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Dr. Moffett’s Teething Powder

Although mercury is highly toxic, various forms of it have been used medicinally for thousands of years, even into the mid-20th century. Mercurous chloride, known as calomel, was used to treat a variety of maladies, including yellow fever. In the 1860s, calomel pills containing mercury were popular for conditions ranging from constipation to depression. Mercury was even used in teething powder until 1948, when it was banned for making children sick. The element mercury and its uses throughout history, along with other subjects, will be explored in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Hornbill beak spoon

According to Malaysian legend, hornbill spoons and buttons would change color in the presence of poison. They are made from the beaks of a large bird, the helmeted hornbill. This spoon, along with other cultural artifacts associated with poisons and antidotes, will be featured in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Amethyst necklace

Jewelry bearing the gemstone amethyst was traditionally worn to protect against poison. The ancient Greeks also thought amethyst could reduce the intoxicating effects of alcohol, so they drank from amethyst goblets; in fact, the word amethyst comes from the Greek word amethystos, or “not drunken.” This necklace, along with other cultural artifacts associated with poisons and antidotes, will be featured in the Museum’s upcoming exhibition The Power of Poison, opening on November 16.

Scientists built largest brain 'connectome' to date by having a lab mouse watch 'The Matrix' and 'Star Wars'

Archaeologists may have discovered the birthplace of Alexander the Great's grandmother

Elusive neutrinos' mass just got halved — and it could mean physicists are close to solving a major cosmic mystery