What America's Forests Looked Like Before Europeans Arrived

European settlers transformed America's Northeastern forests. From historic records and fossils, researchers know the landscape and plants are radically different today than they were 400 years ago.

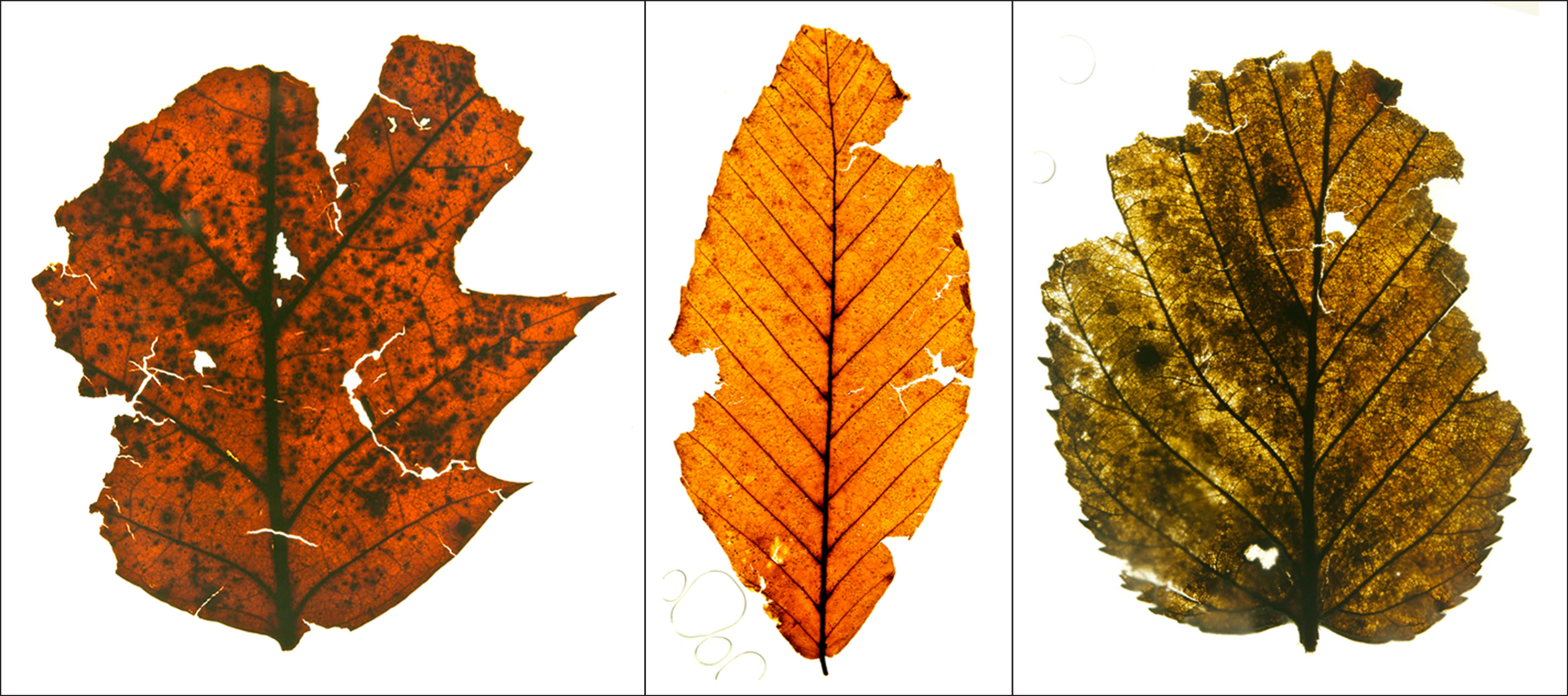

But little direct evidence exists to prove which tree species filled the forests before they were cleared for fields and fuel. Swamp-loving plants, like sedges and tussocks, are the fossil survivors, not delicate leaves from hardwood trees.

Now, thanks to a rare fossil discovery in the Pennsylvania foothills, scientists can tell the full story of America's lost forests.

The fossil site is a muddy layer packed with leaves from hardwood trees that lived more than 300 years ago along Conestoga Creek in Lancaster County, Pa. The muck was laid down before one of Pennsylvania's 10,000 mill dams, called Denlinger's Mill, was built nearby, damming the stream and burying the mud and leaves in sediment.

Researchers from Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa., discovered the fossil leaves while investigating the lingering effects of milldams. The thousands of small dams — which powered mills, forges and other industry — changed the water table, altering the plants growing nearby and eventually changing the landscape from wetlands to deeply incised, quickly flowing streams.

Before Europeans arrived, American beech, red oak and sweet birch trees shaded Conestoga Creek, according to a study the researchers published today (Nov. 13) in the journal PLOS ONE. Some 300 years later, those trees are gone. The same spot is now home to mostly box elder and sugar maple trees, said Sara Elliott, the study's lead author and a research associate at the University of Texas at Austin's Bureau of Economic Geology.

"This is a very unusual opportunity to compare modern and fossil forest assemblages," Elliott told LiveScience. "It's like you're time traveling," she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elliott carefully peeled apart hundreds of leaves stuck together by mud and layered like a pile of sticky notes. Washing the leaves in a variety of chemical baths helped Elliott determine the leaves' structure and species. The research was performed at Penn State University.

Other kinds of trees found in the fossil layer that have since vanished from North America include the American chestnut, which was attacked by an imported fungal disease called the chestnut blight. Leaves from swamp plants also appear in the mud, confirming that the forested spot was on the upslope edge of a nearby wetland. [Image Gallery: Plants in Danger]

"We had a valley margin forest growing right next to the valley bottom in conjunction with all these wetlands," Elliott said. "I think we really have a rather complete picture now of what the landscape was like in this region."

The three dominant tree species found in the fossil forest leaves still exist today in the Northeast, but in different proportions and in different places, Elliot said.

The scientists hope that identifying similar fossil tree-leaf sites will help the massive milldam restoration projects underway throughout the Northeast. The dams left a legacy of toxic sediment piled up behind their walls, as well as reshaped the landscape.

"Having a more complete and enhanced understanding of this past dynamic and complex landscape will help in restoring an ecologically diverse and functional system," Elliott said.

Editor's note: This story was updated Nov. 14 to add that Franklin & Marshall College scientists discovered the fossil leaf site.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.