1st-Century Roots of 'Little Red Riding Hood' Found

Folktales can evolve much like species do, taking on new features and dropping others as they spread to different parts of the world.

One researcher in the United Kingdom tested this analogy quite literally, using analytical models that are typically used to study the relationships between species to create an evolutionary tree for "Little Red Riding Hood" and its cousins.

"This is rather like a biologist showing that humans and other apes share a common ancestor but have evolved into distinct species," Durham University anthropologist Jamie Tehrani explained in a statement. Tehrani found that "Little Red Riding Hood" likely branched off 1,000 years ago from an ancestral story that has its roots in the first century A.D. [5 Real-Life Examples of Fairy Tales Coming True]

"Little Red Riding Hood" is well known to Westerners thanks to the Brothers Grimm. In the story, a girl visits her grandmother's house only to be greeted by a wolf disguised as the old woman. Little Red Riding Hood is promptly devoured after remarking "What big teeth you have, Granny!" But a lumberjack later cuts open the wolf and saves the girl and her grandmother who are miraculously still alive in the beast's stomach.

But there are several other versions of this story from ancient European oral traditions, including variants in which the girl outwits the wolf and escapes after asking to go outside to use the toilet. In another story dubbed "The Wolf and the Kids," which has been told throughout Europe and the Middle East, a nanny goat goes out in the field but first warns her kids not to open the door. A wolf who overhears her warning impersonates the nanny goat, tricks the kids into letting him inside and eats them.

Similar tales also pop up in oral traditions in Asia and Africa. There's "The Tiger Grandmother" in East Asia, for example, in which a group of children unwittingly spend the night in bed with a tiger or monster dressed as their grandmother. After the youngest sibling is eaten, the children get the monster to let them outside to use the toilet and they escape.

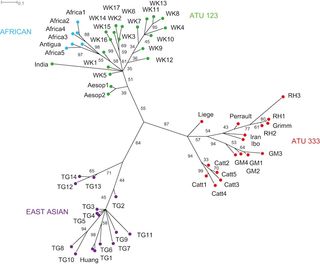

To investigate the possible relationships between these tales, Tehrani looked at 58 variants of the story, focusing on 72 plot variables, such as the number and gender of the protagonists, the ending, and the type of animal or monster that becomes the villain.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tehrani used phylogenetic models — or models that probe the evolutionary relationships among species through time — to compare similarities between these plot variables and determine the probability that they came from the same source. The result is a tree that shows how the story may have evolved.

Tehrani discovered that "Little Red Riding Hood" seems to have descended from the more ancient story "The Wolf and the Kids" — but so did African versions that independently evolved to look like "Little Red Riding Hood."

"This exemplifies a process biologists call convergent evolution, in which species independently evolve similar adaptations," Tehrani explained in a statement. "The fact that Little Red Riding Hood 'evolved twice' from the same starting point suggests it holds a powerful appeal that attracts our imaginations."

The analysis also suggests that the Chinese version of "Little Red Riding Hood" derives from ancient European tales and not vice versa as other researchers have suggested.

"Specifically, the Chinese blended together 'Little Red Riding Hood,' 'The Wolf and the Kids' and local folktales to create a new, hybrid story," Tehrani said. "Interestingly, this tale was first written down by the Chinese poet Huang Zhing, who was a contemporary of Perrault, who first wrote down the European version of 'Little Red Riding Hood' in the 17th century. This implies that the Chinese version is not derived from literary versions of 'Little Red Riding Hood' but from the older, oral version, with which it shares crucial similarities."

The research was detailed Nov. 13 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.