Dictator Deaths: How 13 Notorious Leaders Died

How Dictators Die

Live by the sword, die by the sword? For brutal dictators, the adage is more often than not completely false.

In fact, dictators and warlords are more likely to die of old age or disease than at the hands of an enraged populace or sneaky assassin, according to an analysis by Matthew White, author of "The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities" (W. W. Norton & Company, 2011). White's look back at history found that 60 percent of oppressive warmongering types lived "happily ever after."

There may be little justice for the wicked, but the deaths of dictators do provide some pretty interesting tales. Here's how 13 of the world's most notorious modern leaders kicked the bucket.

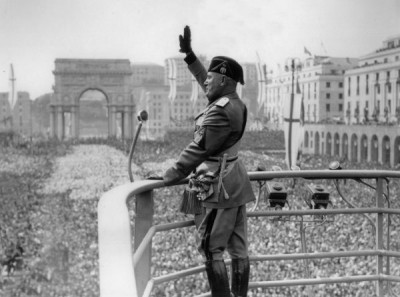

Benito Mussolini, Italy (1883-1945)

Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini was ousted from politics in July 1943 when the country's prospects of victory in World War II soured. The ouster was the beginning of the end for Mussolini; he was immediately arrested and imprisoned at the Hotel Campo Imperatore in central Italy until September, when German paratroopers rescued him. He was taken to Germany, and then Lombardy in northern Italy, but he seemed to know the end was near. In 1945, he told an interviewer, "Seven years ago I was an interesting person. Now I am a corpse."

Just a few months later, he'd really be a corpse. In April 1945, Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci were trying to escape Italy for Spain when they were stopped by communist partisans, taken hostage and shot. Their bodies were taken to Milan's Piazzale Loreto, site of the execution of 15 anti-fascists the year before, and hung upside-down. Passersby spit on the bodies and pelted them with rocks, according to BBC news reports at the time. Photos of the corpses were widely circulated and even sold to American servicemen as grisly souvenirs. [Fight, Fight, Fight: The History of Human Aggression]

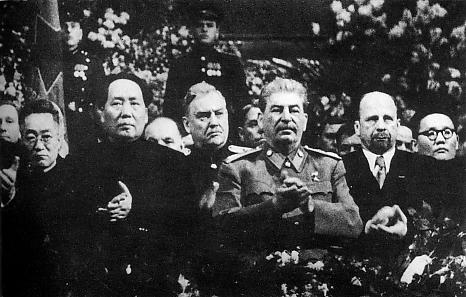

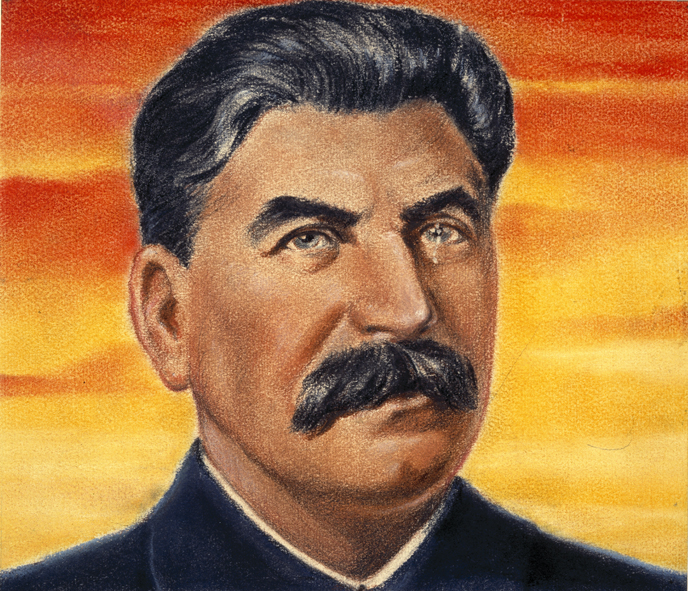

Joseph Stalin, Russia (1878-1953)

Calculating Russian ruler Joseph Stalin's victim count is tough. Official records suggest at least 3 million people died from execution and in prison camps during his reign, but those numbers are likely incomplete, and millions more certainly died in famines caused by his policies. Modern historians peg the number of deaths at between 15 million and 20 million.

Stalin himself lived to the ripe old age of 73. After a late-night dinner and movie with some of his political colleagues, he went to bed in the wee hours of March 1, 1953, and never came out of his room in the morning. His guards, under orders not to disturb their leader, were worried, but too afraid to disturb him. It wasn't until 10 p.m. or 11 p.m. that night that Stalin's underlings gathered the courage to check on him. He was found on the floor, soaked in urine, having suffered a major stroke, but still alive.

A stopped watch on the floor suggested that Stalin had fallen at 6:30 in the morning. He lingered until March 5. Of his last moments, his daughter Svetlana wrote, "At the last moment he suddenly opened his eyes. It was a horrible look — either mad, or angry and full of fear of death. … Suddenly he raised his left hand and sort of either pointed up somewhere, or shook his finger at us all. … The next moment his soul, after one last effort, broke away from his body."

Adolf Hitler, Germany (1889-1945)

Adolf Hitler is a notorious exception to the trend of dictators surviving into old age. In the waning days of World War II, with the Russian Army closing in on Berlin, Hitler holed up in a bunker under the Reich Chancellery building.

As bad news poured into the bunker, Hitler made his preparations to die on his own terms. He heard of Mussolini's death and the desecration of the corpse and ordered that his own body be burned. He married his mistress, Eva Braun, and ordered cyanide capsules tested on a dog belonging to the children of German propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. On April 30, Hitler and Braun went into a lower room in the bunker. Braun apparently took cyanide, while Hitler shot himself in the temple. Hitler's lieutenants followed his wishes and burned the corpses, though the burning was not thorough. The Russian army discovered the remains, identified the bodies, and then destroyed what was left to prevent Hitler's grave from becoming a shrine. [Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal With the Dead]

Francisco Franco, Spain (1892-1975)

Francisco Franco ruled Spain from 1939 until his death. He censored his opponents, created political concentration camps and instituted the death penalty for some who spoke out against him.

Franco's health declined as he entered his late 70s, and he had largely stepped back from day-to-day politics by the time of his final illness. The dictator had been battling Parkinson's, a degenerative disease that causes problems in movement. On Oct. 30, 1975, he lapsed into a coma. He survived on life support until Nov. 20, and then died at the age of 82.

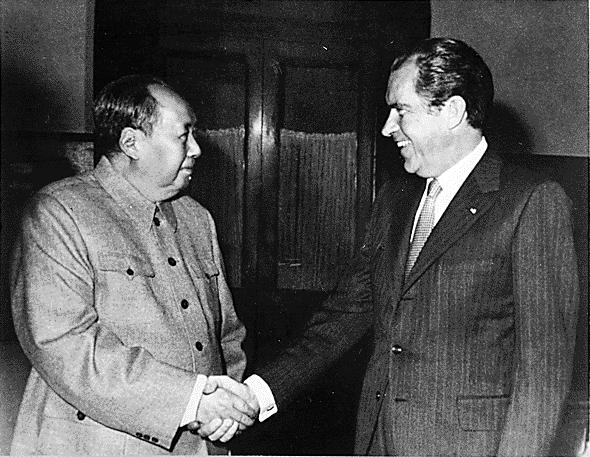

Mao Zedong, China (1893-1976)

Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong also made it to age 82. Like Franco, he suffered from poor health for a long time before his death; the last time he was seen in public was in May 1976. It's not clear exactly what ailed Mao, but he may have had Lou Gehrig's disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a degeneration of the nerve cells that control movement.

Mao had a heart attack on Sept. 2, 1976, that proved to be his downfall. Over the next several days, he suffered various crises, including a brush with death from a worsening lung infection. On Sept. 7, Mao fell into a coma from which he never awoke. Doctors took him off life support a day later, and he died a few minutes after midnight on Sept. 9.

Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier, Haiti (1907-1971)

Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier was elected to the presidency in Haiti in 1957 and immediately began consolidating power, exiling his opponents' supporters, supervising torture of political dissidents and ordering executions of those who crossed him. A practitioner of the voodoo religion, Duvalier occasionally communed with the severed heads of his victims.

Duvalier was plagued by health problems, however, including a heart attack in 1959. His chronic diabetes and heart troubles eventually killed him in 1971.

Kim Il-sung, North Korea (1912-1994)

Kim Il-sung [JB1] was the first leader of North Korea, taking the office in 1948 and establishing a hereditary dynasty. His grandson, Kim Jong-un, now rules the country —though technically, Kim Il-sung is still president, as he was proclaimed to hold that position into eternity after his death in 1994.

Kim's regime created an insular North Korea almost unimaginably isolated from the outside world. Still, he could not hide his own decline: By the late 1980s, a bony tumor on his neck was visible in official news broadcasts, even as he tried to stand in such a way to hide the growth from the camera.

It was a heart attack that ultimately did Kim in, however. The leader collapsed suddenly on July 8, 1994, and died several hours later. He was 82.

Augusto Pinochet, Chile (1915-2006)

Augusto Pinochet came to power by military coup in 1973. His regime killed and imprisoned dissidents and tortured thousands of citizens.

Pinochet stepped down peacefully in 1990 and handed power to the democratically elected Patricio Aylwin Azócar. The human rights abuses of his time in power came back to haunt him, however. He was placed under house arrest in Great Britain in 1998 and only released back to Chile two years later for medical reasons, including mild dementia.

The legal battles wore on as Pinochet's health continued to spiral downward. On Dec. 3, 2006, less than two months after being charged with 36 counts of kidnapping, 23 counts of torture and one count of murder, Pinochet suffered a final heart attack. He died, surrounded by family, in intensive care on Dec. 10 of pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure, never having been convicted of his crimes.

Nicolae Ceausescu, Romania (1918-1989)

The last Communist leader of Romania met his end on Christmas Day, 1989. The national mood was rebellious that December, and Ceausescu tried to soothe the populace with a public (yet carefully controlled) speech on Dec. 21. The crowd booed him. Ceausescu's uncomprehending look at being heckled helped bolster the rebellion against him.

The next day, Ceausescu and his wife, Elena, escaped Bucharest by helicopter minutes ahead of an angry mob. The respite was temporary; the couple was taken into custody by the army, given a show trial, and sentenced to death for genocide and corruption. Though there was nominally a 10-day period to contest the ruling, the execution commenced immediately: The Ceausescus hands were tied and they were forced against a wall, where a firing squad riddled them with bullets. One member of the execution team, Dorin-Marian Cirlan, later described the experience as haunting. "He looked into my eyes and realized that he was going to die right then, not sometime in the future, then started to cry," Cirlan said of Ceausescu. [10 Contested Death Penalty Cases]

Idi Amin, Uganda (Approx.1925-2003)

Hundreds of thousands died in Uganda under the rule of Idi Amin, who came to power in a military coup in 1971. Amin was deposed and exiled in 1979. He settled in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where he lived in comfort for years.

Amin went into a coma caused by kidney failure in July 2003 and died in early August, his fifth wife by his side. News reports at the time blamed his weight, which may have ballooned to as high as 485 pounds (220 kilograms) by the time of his death. Amin's exact birth year is unknown, but he was likely around 80 when he died.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.