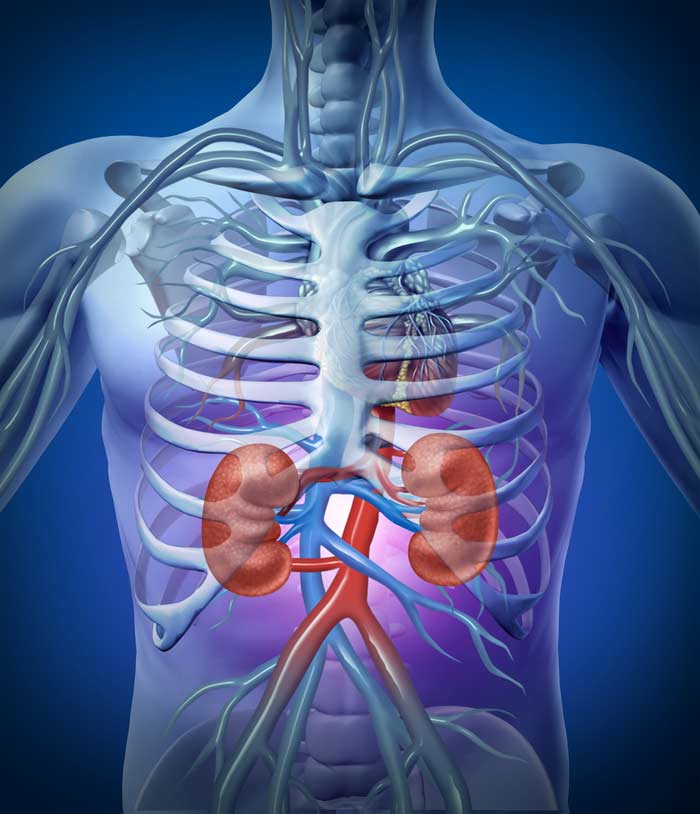

3D-Printed Kidneys Take Small Steps Toward Organ Replacements

A model of a 3D-printed kidney drew wild applause when a surgeon first held it up at a TED conference in 2011. But the dream of creating replacement human kidneys using 3D-printed technology still remains years away, even as the technology has enabled the rise of "bioprinting" aimed at building organs suitable for transplantation.

Kidneys represent the human organ in highest demand among the more than 120,000 U.S. patients currently waiting for organ donations. Researchers hope that new generations of 3D printers can use living human cells to build replacement organs layer by layer — especially organs such as livers, hearts and kidneys.

"These are by far the most complex, because you have a lot more cells per centimeter than any other organ, and because you have so many cells that are functionally complex," said Tony Atala, director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Atala helped pioneer the idea of building artificial scaffolds in the shapes of organs and seeding them with living cells in the lab. That allowed his team to create and implant tissue-engineered bladders into seven young volunteers in 1999. Now he has set his sights on the more challenging task of building more complex organs such as kidneys with the help of 3D printing — the process he demonstrated with the 3D-printed model in the shape of a kidney in front of the TED crowd in 2011. [7 Cool Uses of 3D Printing in Medicine]

But the hype surrounding the futuristic idea of bioprinting can prove misleading. News headlines mistakenly reported that Atala had held up a real living kidney on the TED stage in 2011. This year, breathless news reports also overhyped the work of a Chinese team at Hangzhou Dianzi University of Electronic Science and Technology that had 3D-printed a mass of living cells in the shape of a miniature kidney.

"They printed the shape of it, but they're not printing at the level of individual cells yet," said Stuart Williams, executive and scientific director of the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute in Louisville, Ky. "That's one of the limitations of 3D printing."

Even the finest next-gen 3D printers won't be able to print human tissue at small enough scales to match the real-life complexities of human organs, Williams explained. Similar problems have prevented 3D printing from building the tiny networks of blood vessels required to keep full-scale organs healthy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The kidney represents a special challenge for 3D printing, because of its detailed, tiny structures that allow the organ to filter out waste chemicals from blood and turn the waste into urine. Bioprinting researchers hope to take advantage of the self-organizing tendencies of stem cells extracted from patients to fill in the missing details and knit together full-size organs.

"It's going to be hard to get a full-size kidney with 3D printing alone, without nurturing biological activity and encouraging [the organ] to grow into its final form," said Keith Murphy, CEO of Organovo, a San Diego-based startup.

A 3D-printed kidney, like other 3D-printed replacement organs, likely won't become a reality within the next 10 or 15 years, researchers say. But they plan to use the simplified, miniature versions of 3D-printed organs created so far as guinea pigs for pharmaceutical drug testing — an idea that could help scientists to discover drugs suitable for humans more efficiently and ethically than animal testing.

You can follow Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @jeremyhsu. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.