'Secret' Labyrinth of Tunnels Under Rome Mapped

Deep under the streets and buildings of Rome is a maze of tunnels and quarries that dates back to the very beginning of this ancient city. Now, geologists are venturing beneath Rome to map these underground passageways, hoping to prevent modern structures from crumbling into the voids below.

In 2011, there were 44 incidents of streets or portions of structures collapsing into the quarries, a number that rose to 77 in 2012 and 83 to date in 2013. To predict and prevent such collapses, George Mason University geoscientists Giuseppina Kysar Mattietti and scientists from the Center for Speleoarchaeological Research (Sotterranei di Roma) are mapping high-risk areas of the quarry system.

The mapping is important, Kysar Mattietti told LiveScience, because through the years, Roman citizens have taken the patching of the quarry systems into their own hands. [Photos: The Secret Passageways of Hadrian's Villa]

"The most common way is to take some big plastic bags and fill them with cement and stick them in the holes," she said.

Lucky geology

Volcanism created the land Rome was built upon. These volcanic rocks, or tuff, were a boon to Rome's earliest architects, who soon learned the tuff was strong and easy to carve into building blocks. Lighter, less compacted volcanic ash was used as a main ingredient in mortar.

The first Romans were savvy, Kysar Mattietti said. The geoscientists quarried outside the city, and found that even when the suburbs began to encroach over the quarries, the ancient Romans knew to keep the tunnels narrow enough so that the ground above was still supported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But two things worked against the long-term stability of the tunnels.

The first was Mother Nature. As soon as the rock is exposed to air, it starts to weather, Kysar Mattietti said. The second problem was human. Later generations kept building, using the same quarries for rock and widening the tunnels beyond their original size to create new structures above them.

Secret passageways

The tunnels are something of an open secret in Rome. Over the years, once quarrying ended, people repurposed the underground labyrinth as catacombs, for mushroom farming and as an unofficial sewer system. During World War II, people used the tunnels as bomb shelters.

But younger Romans are less aware of the geological hazard under the city, Kysar Mattietti said. And few realize the quarries' extent.

"Since they weren't serving any use, people tend to forget what can be a problem," Kysar Mattietti said.

Now, Kysar Mattietti and other geoscientists are using laser 3D scanning to search for hidden weaknesses in the tunnels. The researchers also enter the tunnels through manholes and map the labyrinth by hand once they're sure the area is safe.

"There might be cracks, so they will be showing as veins almost, or openings, so we map the openings and map any kind of detachment," she said. In some spots, the ceiling of the tunnel sloughs off like cracking plaster. In others, there are total collapses — sometimes not reaching quite to street level, but leaving very little ground between the surface and the void.

"It's interesting, because at times when you are down there, you can hear people on top," Kysar Mattietti said.

To fix critical points, city officials seal off the unstable point and pour mortar into the tunnel, filling the entire void instead of simply patching over the top.

"What the municipality wants to do is to basically have a map of the risk so at that point they can on their side decide what kind of intervention needs to be done," Kysar Mattietti said.

The geoscientist presented her mapping work this October at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver.

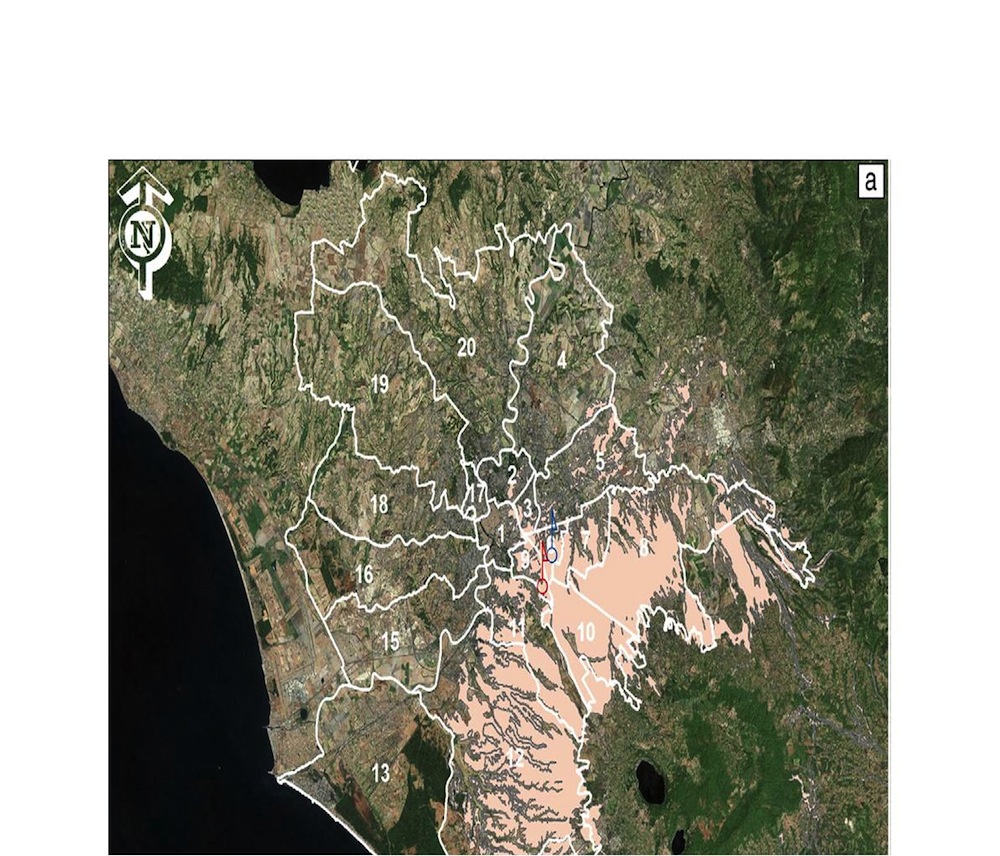

Most of the quarrying is under the southeastern area of the city. Kysar Mattietti and her team are currently mapping three sites considered at particularly high risk of collapse. The need will likely only increase as natural erosion works its destructive magic in the quarries.

"A crack never stops on its own," Kysar Mattietti said. "It always gets bigger."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.