Comet ISON's Thursday Sun Encounter a Thanksgiving Feast for NASA

The icy Comet ISON from the depths of deep space will either meet its doom or transform into a cosmic spectacle when it whips around the sun Thursday (Nov. 28) in a Thanksgiving Day treat for NASA and scientists around the world.

"It's a wonderful holiday roast for all the scientists," NASA scientist Michelle Thaller said in an interview (Nov. 26) of the comet's timely arrival on the U.S. holiday. "While many people will be roasting their turkeys, the sun will be roasting this comet."

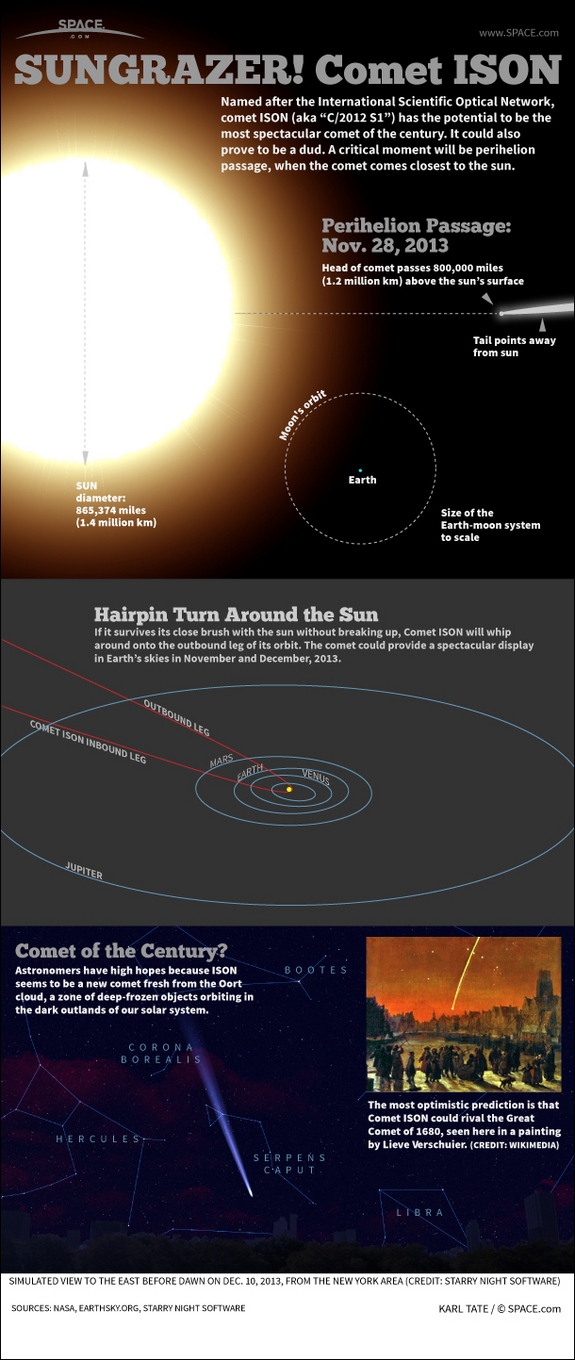

The much-anticipated Comet ISON will give the sun the closest of shaves on Thursday (Nov. 28) at 1:38 p.m. EST (1838 GMT) when it comes within 684,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) of the solar surface, NASA officials said. But despite more than a year of tracking, the big question remains: Will Comet ISON survive its fiery solar encounter, or will it disintegrate in puff of ice and dust? [Comet ISON's Sun Encounter: Complete Coverage]

"This comet has given us quite a ride," Carey Lisse, a senior research scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, told reporters in a NASA teleconference Tuesday. "It's hard to predict what's going on now."

Comet ISON was first discovered in September 2012 by Russian amateur astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok. Since then, scientists and stargazers on the ground have tracked the comet's progress to see if ISON would live up predictions that it could become a "comet of the century."

Lisse said his personal view is that ISON has a 40 percent chance of surviving its sun flyby.

"I'd be thrilled to be wrong," he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

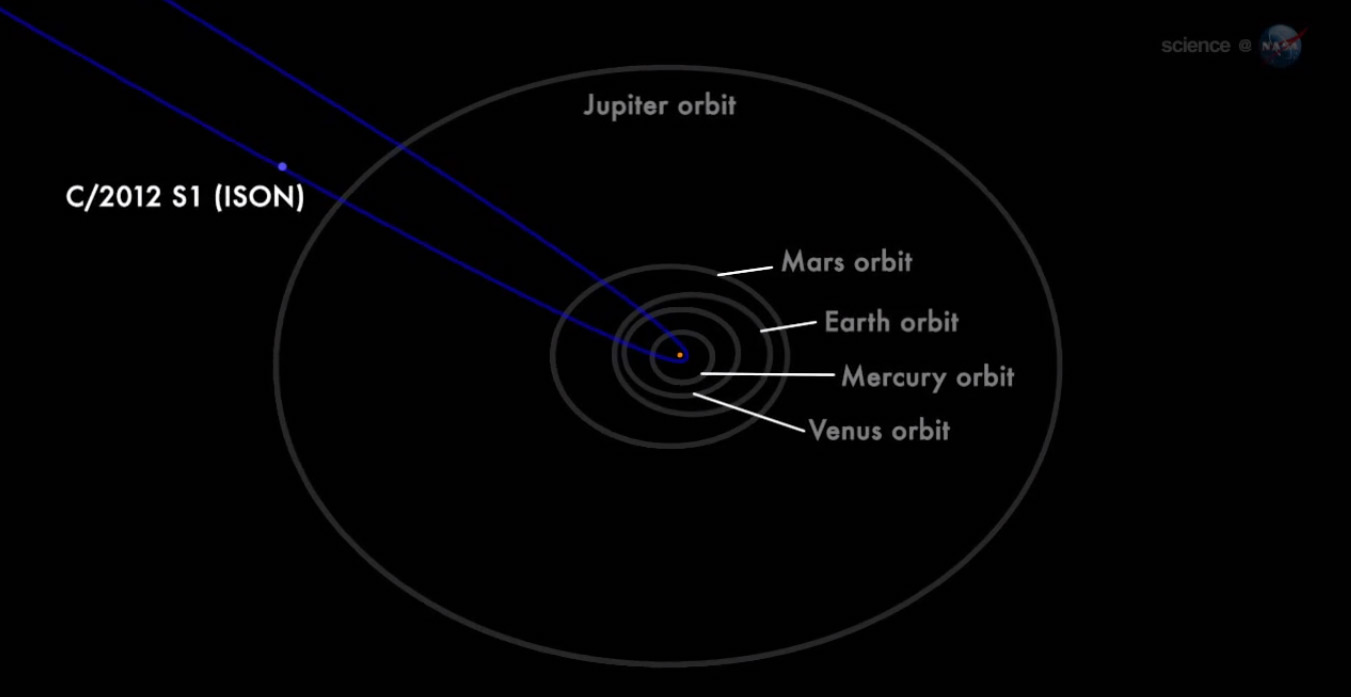

The major draw of Comet ISON is its history. The comet comes from the Oort cloud, a vast cloud of icy objects that surrounds the solar system. ISON is a remnant from the original ingredients that formed the solar system 4.5 billion years ago. The comet is less than a mile wide and made up of 2 billion tons of ice and dust, Thaller said. [Photos: Amazing Views of Comet ISON by Stargazers]

According to Lisse, ISON began its trip into the inner solar system long ago, during the "dawn of man," and it won't be seen again for millions of years, if ever.

"What we know of the orbit right now, it should escape into the Oort cloud and never come back," Thaller told SPACE.com. "This is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see the comet."

On Thursday, NASA scientists will spend the Thanksgiving holiday tracking ISON with the agency's Solar Dynamics Observatory, STEREO probes and the SOHO observatory operated by NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA will also hold a live Google Hangout from 1 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. EST (1800 to 2030 GMT) to

showcase views of the comet during its closest approach to the sun. You will be able to watch the Comet ISON hangout live on SPACE.com here.

Initially, Comet ISON did not grow as bright as its predictions had suggested, but in recent weeks the comet flared up dramatically, making it visible to the naked eye about an hour before dawn in the southeastern sky. Just two days ago, the comet experienced another outburst and then settled down, according to images from sun-watching spacecraft like NASA's twin STEREO probes and the SOHO observatory.

On Thanksgiving, Comet ISON will be too close to the sun to be spotted by the naked eye by the casual observer, but it should by crystal clear in views from space-based observatories.

"This is really a critical time, arguably the most critical time, for Comet ISON," said astrophysicist Karl Battams of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. "It is experiencing the most intense solar radiation and the most intense gravitational forces."

As the ice and dust boils off from Comet ISON near the sun, scientists will be able to learn more about what the comet is made off. The solar passage also offers a chance to study how the atmosphere of the sun behaves, too, Thaller said.

"The neat thing about catching these comets when they're very close to the sun is that we can actually use them as a probe to see what conditions are like close to the sun itself, the magnetic field, the solar wind," she added.

Even if Comet ISON doesn't survive its close encounter with the sun, it could still transform into a remarkable night sky object. In 2012, the Comet Lovejoy was destroyed during a similar solar flyby, but its tail lived on creating dazzling views for skywatchers on Earth, Lisse said.

If ISON's tail or entire body do survive, they would likely be visible from the Northern Hemisphere about 10 days after the sun flyby. [Related: Comet ISON: An Observer's Guide]

"Starting in early December, we will actually be able to see it fairly close to dawn in the sky. It's actually very close to the sun," Thaller said. "As December goes on, it will get farther way from the sun, and it will be up in the night sky. By the time you get to mid to late December, if you look up to about the Big Dipper, it should be right there if it survives the sun."

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing picture of Comet ISON or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

You can follow the latest Comet ISON news, photos and video on SPACE.com.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Tariq is the editor-in-chief of Live Science's sister site Space.com. He joined the team in 2001 as a staff writer, and later editor, focusing on human spaceflight, exploration and space science. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times, covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University.