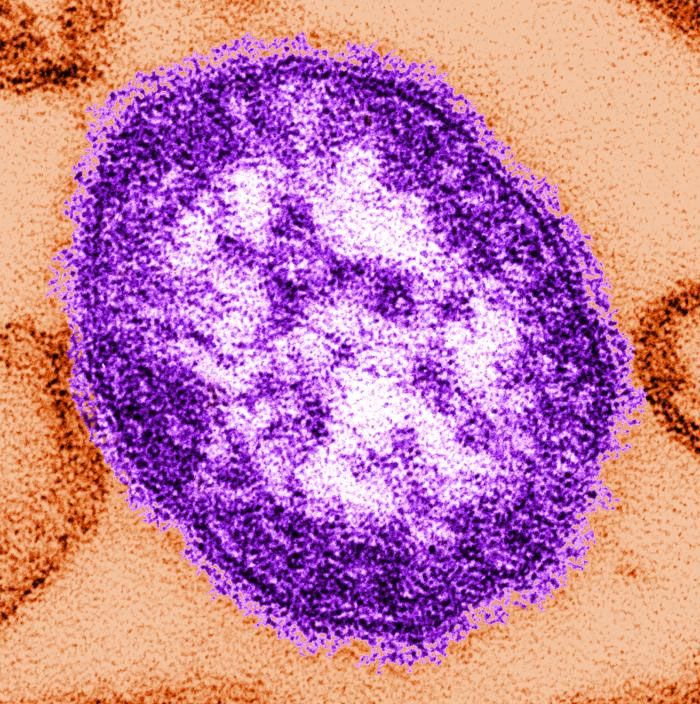

Measles Cases Spiked in 2013, CDC Reports

Nearly 200 cases of measles have been reported in the United States so far this year, making 2013 one of the worst for measles outbreaks in the last decade, according to new numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Typically there are about 60 cases of measles in the U.S. yearly, but in 2013, there have been 175 cases as of Nov. 30. Since 2000, the only other year with more cases of measles was 2011, when there were 222 measles cases.

This year also saw the largest single outbreak of measles in 17 years, when the virus sickened 58 people in an orthodox Jewish community in New York.

Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000. In public health terms, "eliminated" means there is no longer a continuous spread of measles in the U.S., but sporadic cases do occur.

Cases usually occur when a person is infected with measles in another country, and brings the virus back to the United States. When this happens, outbreaks can pop up, particularly in pockets of unvaccinated people. Nearly all measles cases in 2013 could be traced back to an infection that occurred abroad, the CDC said. [5 Dangerous Vaccination Myths]

The increase in cases in 2013 serves as a reminder that measles cases anywhere in the world have the potential to cause an outbreak in the United States, said Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the CDC.

"A measles outbreak anywhere is a risk everywhere," Frieden said. "The steady arrival of measles in the United States is a constant reminder that deadly diseases are testing our health security every day."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Measles is a highly contagious respiratory disease caused by a virus that can cause serious illness, and is responsible for about 164,000 deaths around the world each year. "It is capable of picking out whoever is susceptible from even a large crowd," Frieden said today in a news conference.

A study published today (Dec. 5) in the journal JAMA Pediatrics confirms that measles has indeed remained eliminated in the U.S. since 2000, with an infection rate of less than 1 case per 1 million people each year.

Still, there were 911 measles cases between 2000 and 2011, the report said, and about 65 percent of infected people were unvaccinated. (An additional 20 percent had an unknown vaccination status.)

At least 88 percent of cases were confirmed as linked to a person who became infected in another country. For the remainder of the cases, a source could not be identified.

If measles is to remain eliminated in the United States, the country must maintain high levels of vaccination, the researchers said. Because the disease is so contagious, a high percentage of the population must be vaccinated to prevent outbreaks, the CDC said. "The disease is remarkably infectious, but the vaccine is remarkable effective," Frieden said.

The United States still has clusters of unvaccinated people, often because they reject the vaccine, said Dr. Alan Hinman, director for Programs at the Center for Vaccine Equity at the Task Force for Global Health.

The CDC is also working together with other countries to prevent measles worldwide. Since 2001, a global partnership that includes the CDC has vaccinated 1.1 billion children against the disease, the agency said.

"With patterns of global travel and trade, disease can spread nearly anywhere within 24 hours," Frieden said. "That’s why the ability to detect, fight and prevent these diseases must be developed and strengthened overseas, and not just here in the United States."

The CDC today also honored Dr. Samuel L. Katz, who played a major role in creating the measles vaccine 50 years ago. Because of the vaccine, it is estimate that, over the last 5 decades, at least 30 million children survived who would have otherwise been killed by measles, Frieden said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

2nd measles death reported in US outbreak was in New Mexico adult

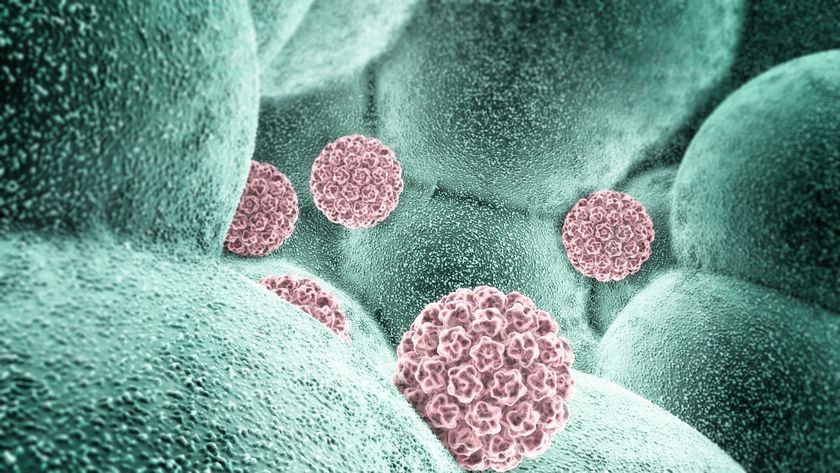

CDC data reveal plummeting rate of cervical precancers in young US women — down by 80%