Undersea Cliff May Hold Clues to Dinosaur-Killing Cosmic Impact

This article was updated at 12:55 p.m. ET on Dec. 11 to add comments from the project's lead researcher.

Scientists have mapped a dramatic undersea cliff in the southern Gulf of Mexico that could hold clues to the ancient cosmic collision that wiped out the dinosaurs.

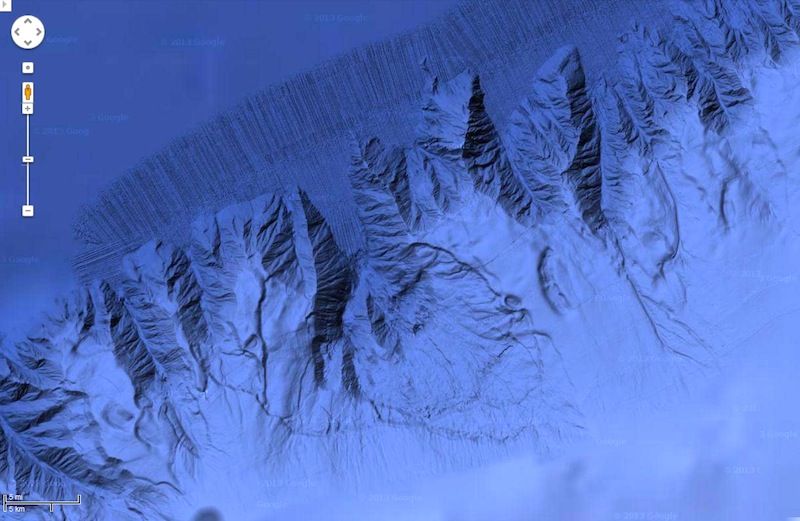

Stretching some 372 miles (600 kilometers) long with steep sides that rise about 13,100 feet (4,000 meters) above the seafloor, the so-called Campeche Escarpment might rival a wall of the Grand Canyon in its splendor were it not underwater.

Scientists are interested in studying the cliff in part because it is located near the site of a devastating asteroid or comet impact that occurred 65 million years ago. Researchers believe the crash sparked firestorms and sun-blocking dust clouds that led to a global extinction event, ending the dinosaurs' 150-million-year reign on Earth. [Images: Undersea Search for Clues of Dinosaurs' Demise]

The impact crater that was left behind, called the Chicxulub crater, is buried deep underneath the Yucatan Peninsula today. So far, researchers have only been able to access impact deposits at the site by drilling deep boreholes on the peninsula. But some researchers suspect more impact deposits might be exposed underwater, along the Campeche Escarpment.

In March 2013, a team of scientists with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) set out to explore the cliff aboard the research vessel Falkor, operated by the Schmidt Ocean Institute. Using multi-beam sonars, the researchers created the first detailed maps of the cliff, which have been incorporated into Google Maps and Google Earth.

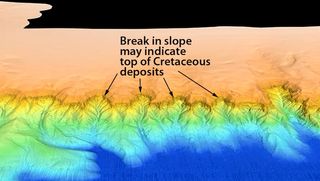

Over time layers of sediment or rock accumulate on top of older layers, making a vertical slice through a system like the Grand Canyon somewhat like a timeline of the past, with the most recent layers on top. Based on the new maps, MBARI scientist Charlie Paull thinks there is visible evidence of such geological processes in the Campeche Escarpment, where exposed layers represent deposits from before, during and after the impact. Images from MBARI even show the spot where Paull and colleagues think layers from Cretaceous age meet younger sediments deposited after the impact event.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Seeing the detailed shape of this feature was eye-opening for several reasons," Paull told LiveScience in an email. "One of the biggest surprises is how easy it is to identify the top of the layer, which is ostensibly the top of the event layer."

Paull said this underwater tier forms a "very distinct horizon" that is visible for hundreds of kilometers along the face of the escarpment, adding that in many places, this level is exposed without a significant sediment cover.

"Another surprise," Paull said, "is that there are more than 80 submarine canyons along the face of the Campeche Escarpment. Before this cruise we only knew of 3 canyons along the 650 km long feature."

Further study of these sediments might shed light on the destruction unleashed by the ancient impact. The researchers hope it might be possible to collect samples from the Campeche Escarpment using underwater robots, or perhaps even manned submarines.

The work was being presented at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco this week.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.