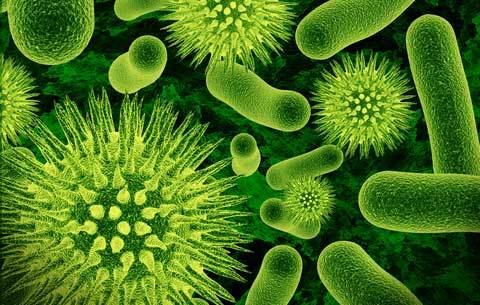

A New Diet Quickly Alters Gut Bacteria

The types of bacteria in your gut today may be different tomorrow, depending on what kinds of food you eat, a new study suggests.

In the study, participants who switched from their normal diet to eating only animal products, including meat, cheese and eggs, saw their gut bacteria change rapidly — within one day.

While the participants were on the animal-based diet, there was an increase within their guts in the types of bacteria that can tolerate bile (a fluid produced by the liver that helps break down fat), and a decrease in bacteria called Firmicutes, which break down plant carbohydrates. [5 Ways Gut Bacteria Affect Your Health]

Gut bacteria also tended to express (or "turn on") different genes during the animal-based diet, ones that would allow them to break down protein. In contrast, the gut bacteria of another group of participants who ate a plant-based diet expressed genes that would allow them to ferment carbohydrates.

The differences between the gut bacteria of the people on the plant-only and animal-only diets "mirrored the differences between herbivorous and carnivorous mammals," the researchers wrote in the study published today (Dec. 11) in the journal Nature.

Researchers knew that a person's diet affects his or her gut bacteria, but it wasn't clear just how quickly this happens.

The researchers said they were surprised by their results. "We weren’t at all sure it was going to happen this quickly in humans," said study researcher Lawrence David, an assistant professor at Duke University's Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings suggest "the choices that people make on relatively short time scales … could be affecting the massive bacterial communities that live inside of us," David said.

The study also adds evidence to the idea that human diets — acting through the gut bacteria — influence the risk of certain diseases. People on the animal-based diet had higher levels of a bacterium called Bilophila wadsworthia, which grows in response to bile acids and has been linked with inflammatory bowel disease in mice, according to the study.

This finding supports a link between dietary fat (from animal fat), bile acids and an increase in growth of microbes that may affect the risk of inflammatory bowel disease, the researchers said.

People who ate the plant-based diet saw fewer changes in the abundance of bacterial species in their gut than people who ate the animal-based diet. This may have, in part, been due to the fact that humans produce bile acids in response to eating animal products, and bile acids, in turn, influence bacterial growth, according to the researchers.

The study included 10 people (six men and four women) ages 21 to 33. One of the participants was a lifelong vegetarian who switched to eating only animal products, such as eggs and cheese (but not meat), for the study. Participants stuck to their diet for five days, and gave stool samples each day for analysis.

While previous studies have looked at changes in gut bacteria in response to diet, most of these collected samples on a weekly or monthly basis, because it is difficult to recruit volunteers willing to give samples daily, David said.

Because the study was small, the researchers are cautious about generalizing their results to the population as a whole. But "the changes we saw appeared to be uniform across these subjects, suggesting that if we were to recruit more people, we would see similar results," David said.

The study was a collaboration between researchers at Duke, Harvard University, Boston Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Francisco.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.