Monitor Lizards' Breathing May Have Evolved Before Dinosaurs

Monitor lizards breathe by taking in air that flows through their lungs in a one-way loop — a pattern of breathing that may have originated 270 million years ago in the ancestral group that gave rise to dinosaurs, and eventually alligators and birds, a new study finds.

Researchers at the University of Utah, in Salt Lake City, and Harvard University, in Cambridge, Mass., studied unidirectional breathing in monitor lizards, which can be found throughout Africa, China, India and other parts of Southeast Asia. Their findings suggest one-way airflow breathing may have evolved earlier than scientists had thought.

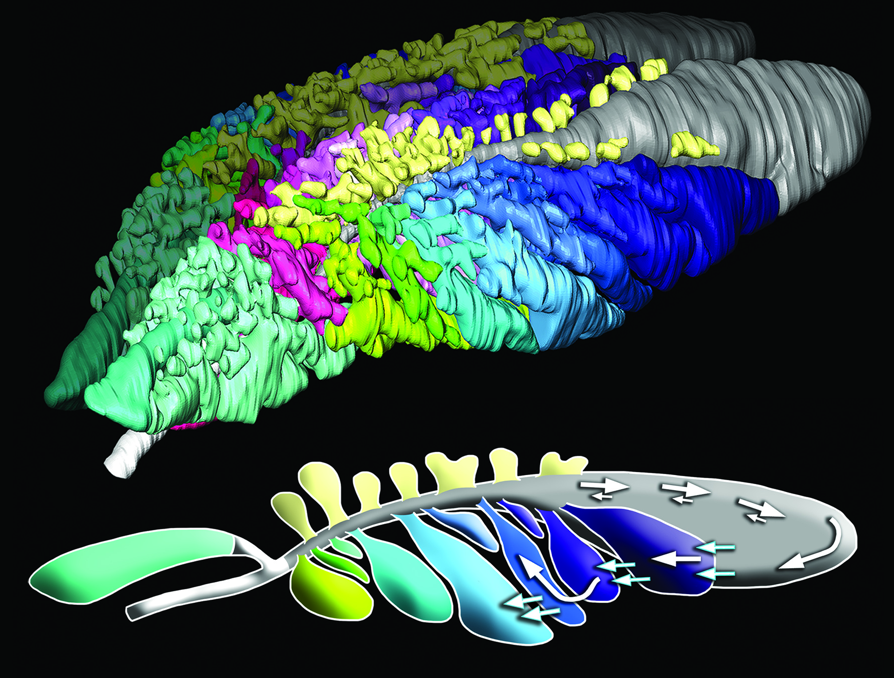

The researchers examined lungs from living and deceased monitor lizards, and found that when these large, often-colorful, carnivorous reptiles breathe, the airflow through their lungs is mostly one-way, unlike in humans and other mammals, which have a "tidal," or two-way, breathing pattern. Human lungs consist of a network of tubes that branch out into progressively smaller airways. Tidal breathing means air enters the lungs through these airways and then flows back out again the same way.

One-way airflow in birds was first suggested in the 1930s, said Colleen Farmer, an associate professor of biology at the University of Utah and senior author of the new study. [Images: Exotic Lizards Pop Out of the Ground in Florida]

"It was first noted in birds that were living in train stations in Europe," Farmer told LiveScience. "They were burning coal to power trains and noticed that only one part of the bird's lung was getting black with soot."

This method of breathing was thought to have evolved in birds to help them extract higher amounts of oxygen from their environment. Since air travels in only one direction through birds' lungs, more oxygen is transferred through their respiratory systems with each breath, which enables them to fly at high altitudes, where oxygen levels are low, without getting winded or passing out.

Similarly, it was speculated that one-way airflow may have helped the ancestors of dinosaurs roam the Earth beginning roughly 251 million years ago, after the Permian-Triassic mass extinction that wiped out up to 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrate species. Following the devastating extinction event, which formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic periods, the level of atmospheric oxygen was thought to be significantly lower than today's levels.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2010, Farmer published a study detailing similar unidirectional airflow in alligators, which suggests the breathing pattern likely evolved about 250 million years ago, when the ancestors of alligators and crocodiles split from the ancient archosaurs, the group that led to the evolution of dinosaurs, flying pterosaurs and eventually birds.

But now, the discovery of one-way airflow in monitor lizards indicates the breathing method may have evolved even earlier — about 270 million years ago — among cold-blooded diapsids, which were the common, cold-blooded ancestors of present-day lizards and snakes, Farmer said.

"We need to look at other animals in different ecological niches, but I would not be surprised to find that this is very common in other cold-blooded vertebrates," she said.

The detailed findings of the study were published online today (Dec. 11) in the journal Nature.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.