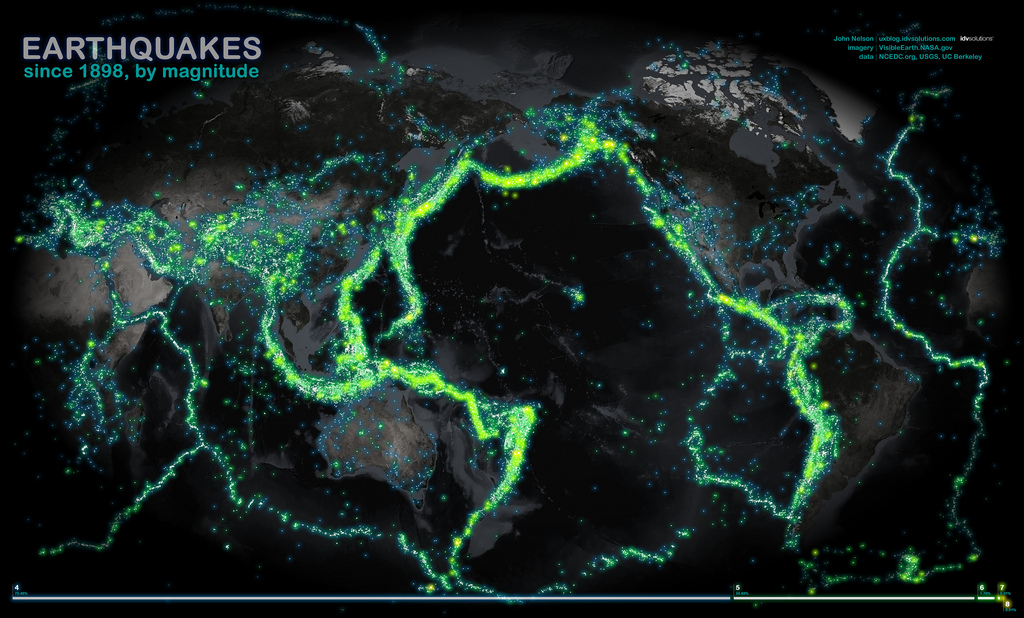

SAN FRANCISCO — The number of great earthquakes experienced in the past may be higher than previously thought, one researcher said here today (Dec. 11) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

As a result, the global community may be underestimating the risk of the next big one, said Susan Hough, of the U.S. Geological Survey.

"There's very compelling evidence that we have underestimated the magnitude of earthquakes in the 19th century and possibly in the first half of 20th century," Hough said.

Prior to about 1900, scientists didn't have an easy way to measure the strength of an earthquake. When seismologists try to recreate historical temblors, they typically look to see whether a tsunami is generated or how far away people felt the quake to get an idea of how strong it was.

But those are imprecise measures. Hough wondered whether many of the past big earthquakes — such as those now classified between about a magnitude-8.0 and a magnitude-8.5 — were underestimated. In the 19th century, for instance, most records say there were just three big earthquakes larger than magnitude-8.5, but 12 in the 20th century. At first glance, that seemed suspicious, Hough said. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"In 1900, we invented seismometers and earthquakes got bigger," she said.

So Hough performed a statistical analysis to see whether there really was a sharp change between the 19th and 20th centuries' rates of large earthquakes. Unfortunately, there weren't enough large earthquakes to draw a firm conclusion, she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Instead, she decided to look at modern earthquakes larger than magnitude-8.5 and see how they compared with earthquakes in the history books, and whether they would have been missed.

The Lesser Antilles earthquake of 1843, for instance, was listed as a magnitude-8.3 earthquake by the National Earthquake Information Center, but was felt all along the Atlantic coast, thousands of miles away. In comparison, the 2012, magnitude-8.6 earthquake in Sumatra was similarly felt from an equivalent distance, according to the USGS' "Did You Feel It" Sensor network, which asks people to report when they feel an earthquake.

An 1841 earthquake in Kamchatka in Russia was listed as a magnitude-8.3 temblor, yet it generated a 15-foot (4.6 meters) tsunami in Hilo, Hawaii. Follow-up research by others suggests it was actually a magnitude-9.2 quake.

Hough also looked at how modern earthquakes would have been classified based on their characteristics. For instance, another earthquake in Sumatra in 2005, a magnitude-8.7 temblor known as the Nias Earthquake, didn't generate a tsunami, and so would have been classified in the past as being approximately a magnitude-7.8 in the catalog.

If these historical big ones are being missed, then the global assessment of seismic hazard, which relies on historical earthquake rates, may be underestimating the biggest possible temblors that could happen, Hough said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.