Polar-bear dens, where mama bears raise young cubs during the harsh Alaska winters, could be identified using laser technology, new research suggests.

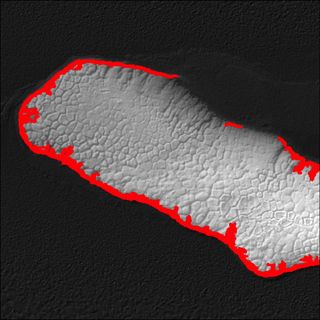

Remotely tracking dens using lidar, an advanced laser technology, can reveal 90 to 95 percent of the dens — a great improvement over past methods, a small pilot study shows.

Knowing where the polar bears rear their young could help protect them from the dangers posed by oil and gas drilling, and could also reveal how the landscape shifts in response to climate change, according to the study, presented Friday (Dec. 13) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

"A lot of oil and gas exploration happens in the winter — that's when bears are in their dens, rearing their young," said study co-author Benjamin Jones, a research geographer with the U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Science Center.

Threatened species

Climate change has threatened polar bears throughout the Arctic. Shrinking sea ice forces polar bears to swim farther to find stable ice on which to hunt for marine mammals and other prey. [Gallery: Polar Bears Swimming in the Arctic Ocean]

These changes mean that the protection of the next generation of cubs is even more important for the species' survival, said study co-author George Durner, a research zoologist with the USGS Alaska Science Center.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The dens are typically dug out of steep snowdrifts with about 30-degree slopes, Jones said.

"Polar bears enter the maternal den in November and exit the den in late March or early April," Durner told LiveScience.

The cubs are born in January and are completely helpless. Inside the dens, the temperature is a relatively balmy 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius), and cubs huddle up next to their moms. But outside, the winds can be howling, and the temperature is often between minus 20 F and minus 30 F (minus 29 F and minus 34 C), Durner said.

Those first few months of uninterrupted time in the den are crucial for the cubs' survival, Durner said. But winter is also prime time for oil and gas exploration. The permafrost and ice roads are stable, making it easier for trucks and other equipment to reach remote sites. The noise could force mama bears out of their dens, and vehicles can sometimes unwittingly drive over a den, Durner said.

In the past, researchers used radar or high-resolution aerial photography — with individual readers wearing stereoscopic headgear — to scan the vast, frozen expanse of Alaska polar-bear habitat. Potential dens were then confirmed by land surveys. But those techniques can't distinguish the fine details in the landscape, meaning those methods missed many of the steep slopes of prime denning areas, Jones told LiveScience.

Better resolution

The team decided to use lidar data that is now becoming available from the oil and gas industries and other sources. When the researchers surveyed the area, they found that lidar could detect most of the denning sites and that the technology was more effective than past methods in picking up potential den sites.

The new technique could also help monitor changes in the landscape — such as permafrost degradation — that may be caused by climate change. Climate change has already altered the bears' denning behaviors, Durner said.

"Sea ice on the Beaufort and Chukchi seas is becoming thinner," Durner said. In response, the bears den there much less frequently, and are forced inland, he added.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular