States Take National Lead in Regulating Fracking (Op-Ed)

Chris Busch is director of research and Veery Maxwell is director of communications, both at Energy Innovation: Policy and Technology. They contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

In the absence of additional federal action to regulate hydraulic fracturing ("fracking"), states have increasingly adopted policies to govern the technology that has opened up large reserves of previously inaccessible natural gas and oil. Fracking is the high pressure injection of large amounts of water, mixed with smaller amounts of chemicals and sand, thousands of feet underground to crack the rock formation and allow trapped hydrocarbons to flow to the surface. California, Illinois and Colorado have recently released draft fracking regulations, adding to an already significant body of existing rules and pending legislation at the state level.

It can be challenging to irrefutably link a particular instance of pollution with a particular oil and gas operation, but evidence is accumulating that environmental damages from fracking are occurring : examples include methane contamination of groundwater supplies, toxic wastewater flooding nearby landsand air pollutant leakage at the well site. Safeguards for public health and the environment need to be in place to protect air, water, and land quality before these extraction techniques are used.

California

In September, California Governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 4 into law, which will establish the state's first requirements specific to the use of hydraulic fracturing in California. On November 15th, state regulators responsible for implementing the bill released their proposed regulations. The proposed regulation covers not only fracking, but other enhanced production techniques including use of acids that are thought to hold the key to accessing California's 15 billion barrels of oil in the Monterey shale. California's faulted geology is more challenging to drill than flat layers of rock. The proposed regulation also requires active notification of landowners and tenants in the vicinity of operations, identification of water sources and water recycling plans, and water quality testing. Additionally, the regulation mandates that the contaminated water produced during extraction be stored in containers, as opposed to sumps or pits. The state has formed an independent panel of scientists to shape the final regulation. The appointed body of experts is set to deliver a report by the end of 2014.

California should also create an expert science advisory panel that regularly informs the regulatory process, since there are many issues associated with fracking that deserve further study. The issue of seismicity, in general, and also long-term performance of the cement used in well casings must be explored. Industry representatives have said that less than one percent of well casings fail immediately, but independent analyses have estimated 3 percent to 15 percent of well casings fail in the first year of operation. This data is not encouraging, given that over 1 million wells have been fracked in the U.S.; California's shifting geology may further increase the risk of cement failure.

Illinois

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

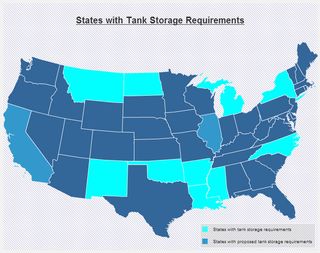

In early 2013, Illinois Governor Pat Quinn signed legislation on fracking into law. Like the proposed regulation in California, the Illinois rules would require water-quality testing before fracking occurs and periodically afterwards, and fracking fluids and produced water would have to be stored in enclosed tanks. The proposed regulations go further than California in requiring a 1,500 foot set-back — a minimum distance of separation — from surface water or groundwater intakes of a public water supply. The Illinois regulations also require transparency, with provisions mandating comprehensive chemical disclosure both before and after fracking occurs, as the actual mix of chemicals occasionally varies from initial plans.

The Illinois law was welcomed strongly by environmental groups. For example, the Environmental Law & Policy Center, based in Chicago, observed: "Collectively, the Act's provisions amount to the strongest protections against fracking-related water pollution in the country." However, since the September release of draft rules, concerns have been raised about an "emergency" clause concerning tank storage and when overflow pits are allowable. Some observers have suggested that the lack of specificity regarding what constitutes an emergency could be a loophole that would render tank-storage requirements all but irrelevant. Illinois is in the midst of a comment period, and is expected to finalize rules early next year.

Colorado

Colorado has recently advanced the regulatory state-of-the-art with a set of proposals aimed at tackling air emissions from oil and gas operations. Once finalized, the rules would make the state the first to directly regulate methane emissions. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, approximately 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The Colorado draft regulations will incorporate innovative leak-detection technology, including infrared cameras that are able to see otherwise invisible leaking gas. The regulations will also be the first to require regular detection and repair of leaks. Additionally, the Colorado regulations include performance standards that will require technological upgrades to reduce leaks, such as improved valves and pumps, which have recently been found to be larger than expected sources of methane. Significantly, the proposed regulations will cover both existing operations and new wells. In addition to methane, the rules will broadly reduce the emission of volatile organic compounds that contribute to smog, equivalent to taking 92,000 cars off the road, according to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission.

By now, transparency has been a common denominator across almost all state and local fracking regulation. In June 2010, Wyoming became the first state to approve rules requiring public disclosure of the chemicals in fracking fluid. In 2011, Texas became the first to enact legislation putting this standard in place. Colorado's rule, the most comprehensive to date, requires drillers to disclose not only chemical names, but also their concentrations. If trade secret protections are invoked, the driller still has to identify the chemical family name.

Like California and Illinois, Wyoming is mandating monitoring of groundwater for contamination. Wyoming regulators enacted a rule in November that requires well and spring testing in a half-mile radius around the well site before and after fracking.

Currently, states like Colorado, Illinois, Wyoming, and California are leading the way in developing the next generation of policy to govern oil and gas production. These efforts must be applauded. Some states have addressed fracking by simply banning the practice until further research is conducted. While this approach is sensible given the unknowns, it has not proved to be politically feasible in major oil- and gas-producing states. There is even less momentum for a moratorium at the federal level. The best hope is for the emergence of strong regulations that enable responsible development.

Action at the state level is attractive because it offers the opportunity to tailor policy to local conditions. But state governments are stretched thin, with many competing regulatory priorities and few resources. Federal policy needs to carry more of the load. A smart federal approach ensures the broadest coverage and consistency across state lines, which is beneficial to companies. In light of this, it is encouraging that a coalition of 90 health, environmental, and sportsmen's groups recently joined together to issue a call for comprehensive federal regulation of methane emissions from oil and gas operations. The public must demand strong fracking regulations at every level; such policies are essential to putting our environment and our energy sources on the path to a clean future.

The authors' most recent Op-Ed was "China Must Avoid Overreliance on Cars." The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.