Recreating an Epic Antarctic Journey: Q&A With Explorer Tim Jarvis

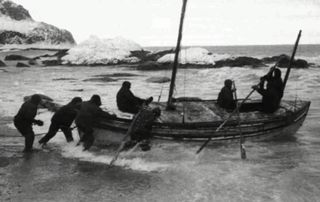

NEW YORK — After famed adventurer Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance was crushed by sea ice in 1914 off the coast of Antarctica, he and his 27 men faced near certain death. But instead of resigning themselves to that fate, Shackleton and five others set out in a small wooden boat and sailed 800 nautical miles (1,480 kilometers) through incredibly rough water to South Georgia, a remote island in the southern Atlantic Ocean that was home to a whaling station. The crew was forced to land on the wrong side of the rocky, ice-covered landmass, and climbed over it with only a single rope and one pickax. They made it, and ended up saving the rest of the crew after convincing another ship to take them back to the spot where Endurance was crippled.

Nearly 100 years later, in January of this year, an Australian explorer and five others did the same thing, using a replica wooden boat, similar tools and even replicas of the clothes Shackleton wore, making the perilous sea journey with century-old navigation equipment and climbing over the mountains and glaciers of South Georgia with almost no tools.

The explorer and writer Tim Jarvis chronicles his team's journey in a three-part PBS special called "Chasing Shackleton" (and a corresponding book of the same title published by HarperCollins) to debut Jan. 8. LiveScience sat down with Jarvis to hear about his incredible expedition.

LiveScience: How was the trip? How did you decide to make the journey?

Tim Jarvis: I was asked by Shackleton's granddaughter to embark on the journey about seven years ago. It took that long to plan and to build the boat, get the right clothing, the old-fashioned navigation equipment and so on.

The crew was comprised of three sailors and three climbers [including Jarvis], all highly skilled and accomplished. Edmund Hillary, the first person to climb Mount Everest, called [Shackleton's feat] the greatest survival journey of all time. Having done it, I'm inclined to agree with him. We sailed in a 22-foot-long [6.7 meter] boat with no rudder, using only a sextant and other old navigation tools.

LS: How long did the trip take?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

T.J.: The boat journey took a couple of weeks. We ate lard like they did in the old days. Old army rations, biscuits and sugary tea. [9 Craziest Ocean Voyages]

It took us 96 hours to cross the island. It only took Shackleton 36 hours. He must have literally bum-slid all the way down some of the steep drops. You'd have to be pretty desperate to go down the slopes that fast, and indeed he was — he had no choice. But like him, we only used leather boots, with screws driven through them, and a single rope that anchored us. One of our team fell into crevices about 20 times and had to be pulled out.

LS: What was the hardest part of the journey?

T.J.: Trying to survive in the Southern Ocean in that little boat, pitching back and forth. Several times we thought we were going to capsize, in which case the person at the helm would've died. Survival time in the water is only 10 minutes.

The second-hardest bit was landing on South Georgia without getting crushed by rocks.

LS: How did you find South Georgia?

T.J.: We used the sextant and other tools to tell when we were at the same latitude as the island, and then we turned right toward it. While getting close to the island, we saw sea grass and birds — you could smell the birds, and see seals and penguins in the water.

LS: What motivated you to embark on this dangerous journey? Was it worth the risk?

T.J.: Yeah, definitely. I can say that now since we all survived.

I think everybody in the project did it because they wanted to test themselves. I don't think you discover who you really are as a person unless you push yourself. You have to take a few risks in life, to find out who you are and really live.

LS: During the journey, did you ever ask yourself why you were doing this, or doubt yourself?

T.J.: That was probably a daily experience, when you're sick and your hands and feet are numb and wondering if the ship will make it another night. But you keep going as long as your reasons to continue outweigh your reasons to stop.

LS: How'd you feel when you finally reached the old whaling station?

T.J.: Very good. It's interesting, when Shackleton got to the whaling station with his compatriots, all of them felt the presence of another person there with them. It's a very well-recorded example of what's called the Third Man phenomenon, where you feel you're in the presence of another person when you're in these difficult, life-threatening conditions.

LS: Have you felt that?

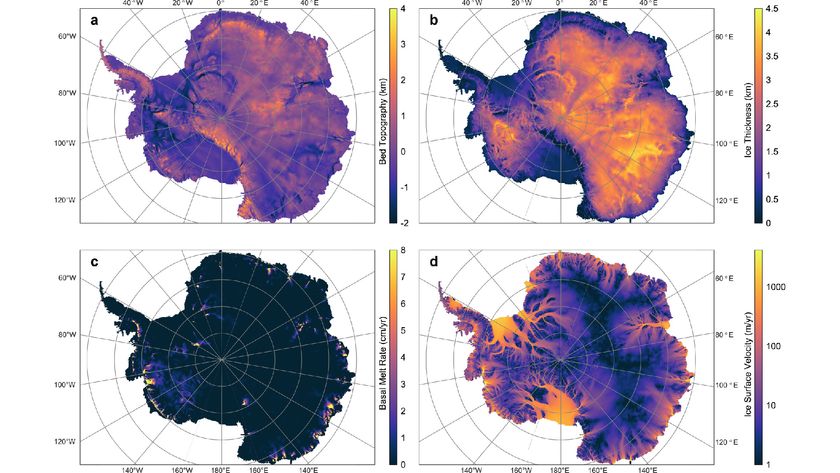

T.J.: Not on this trip, but I have done, in 2006 when I was traveling alone in Antarctica recreating a trip by Douglas Mawson, who traveled through Antarctica by himself after his two compatriots died. I experienced some very strange sensations, heard footsteps in the snow. I was on starvation rations as he was. [Antarctica: 100 Years of Exploration (Infographic)]

LS: You still hold the record for the fastest unassisted trip to the South Pole.

T.J.: That's right. My journey was done with no help. Just me and a sled from the edge of Antarctica. It took 47 days to get to the South Pole from the Weddell Sea. That was a very tough trip. I lost about 40 lbs. (18 kilograms), pulling a sled that weighed about 500 lbs. (225 kg).

LS: What do you hope people get out of the book?

T.J.: I hope some of my messages about the environment come across. Shackleton was trying to save his men from Antarctica, and I'm trying to save Antarctica from men. An enormous amount of change has happened in the 100 years since his voyage.

Two of the three glaciers that were on South Georgia in Shackleton's time were melted. In one case where we expected a glacier, there was a lake that we had to wade across. And 96 percent of the island's glaciers are in retreat.

Populations of penguins, whales and other animals are remarkably lower than they used to be.

I'd also like to tell everybody about the legacy of this incredible leader, Shackleton. He was the embodiment of people putting aside their differences to achieve a goal against enormous odds. We need a dose of Shackletonian leadership to fight against climate change and the like.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.

Most Popular