Byzantine Empire: Map, history and facts

The Byzantine Empire, also called Byzantium, was the eastern half of the Roman Empire that continued on after the western half of the empire collapsed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Byzantine Empire, also known as Byzantium, refers to the eastern half of the Roman Empire that survived for nearly 1,000 years after the western half of the empire collapsed.

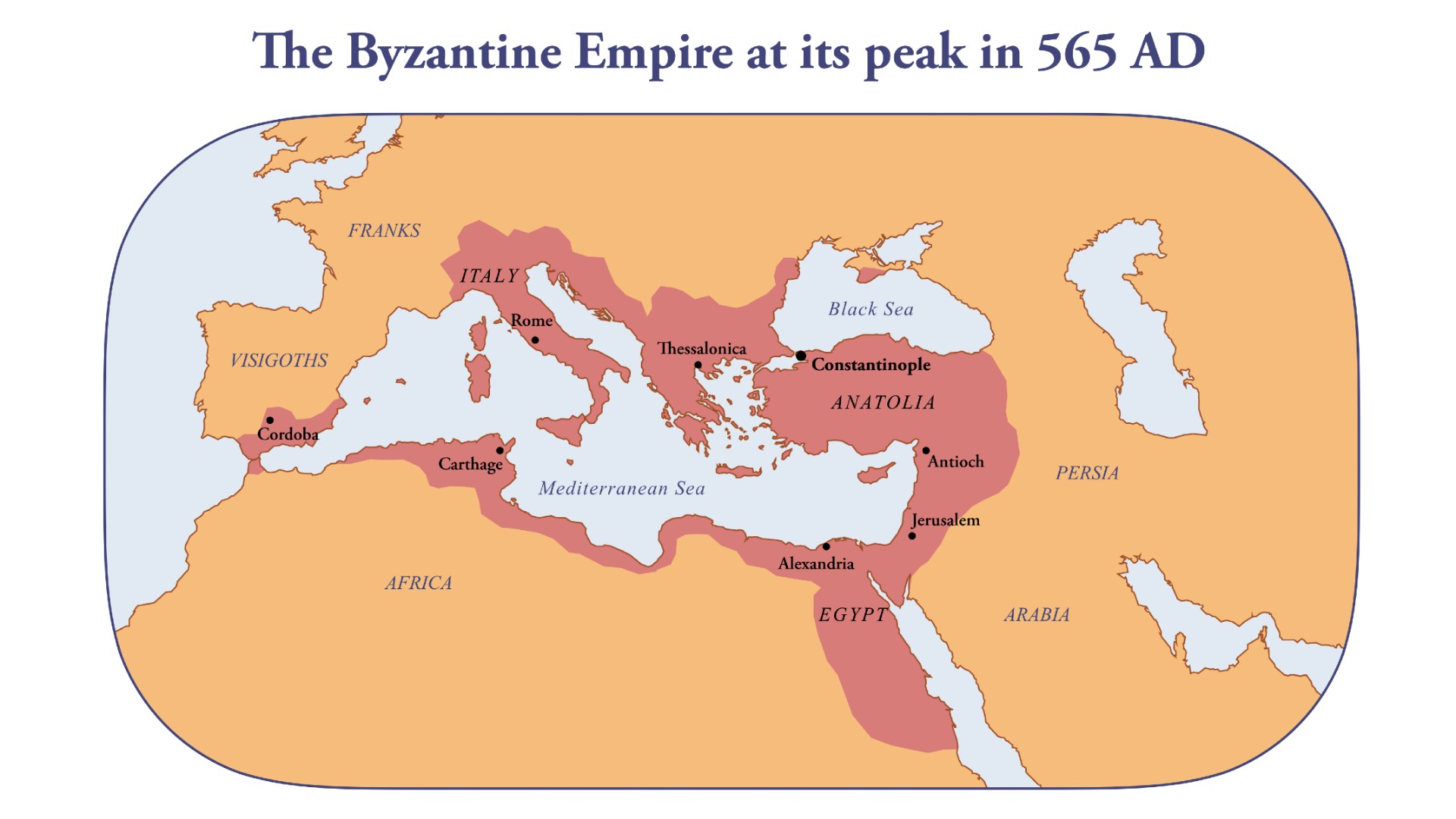

The Byzantine Empire was based at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), and at its peak it controlled territory stretching from southern Spain to Syria.

Throughout their history, the Byzantines rarely controlled Rome and spoke mainly Greek. Despite this, the people of Byzantium continued to refer to themselves as "Romans," Timothy Gregory, professor emeritus of History at Ohio State University, wrote in the book "A History of Byzantium" (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). Their broader empire was considered to be a "Roman" empire even though it rarely controlled Rome.

Article continues belowThe Byzantine Empire eventually fell when Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 following a siege

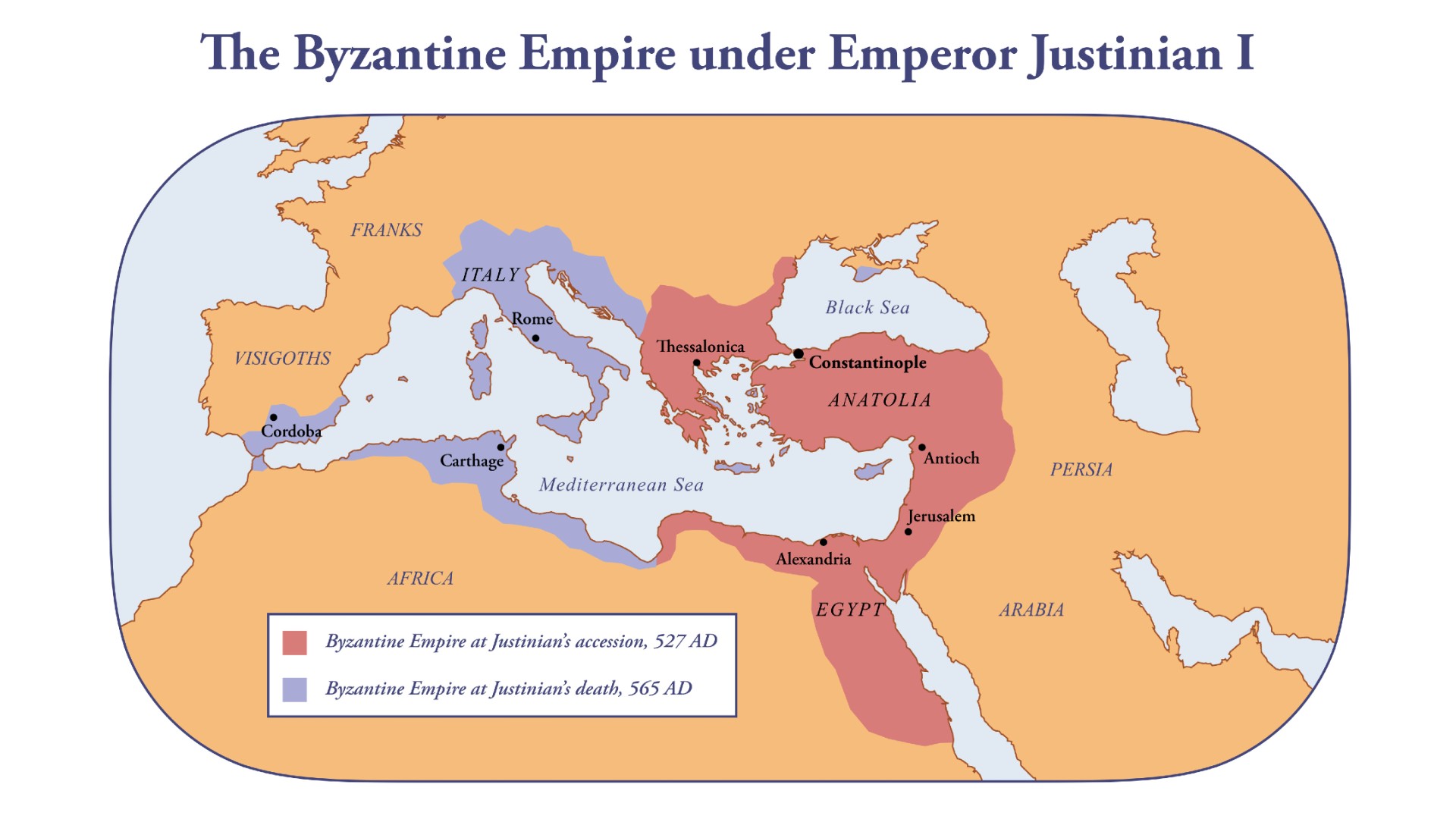

Unlike the western half of the empire, the Byzantine Empire flourished and experienced a "golden age" during the reign of Justinian (A.D. 527 to 565), during which the empire's territories extended into Western Europe, and the emperor's builders constructed the Hagia Sophia, a great cathedral that still stands and is now used as a mosque.

After Justinian's death, the Byzantine Empire weakened and lost territory. In 1204, during the Crusades, the Byzantines were betrayed when crusaders from the west sacked Constantinople in an attempt to gain money.

The Byzantine Empire eventually fell when Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 following a siege.

Origins

By the early fourth century A.D., the Roman Empire covered a huge territory, from northern England to Syria. However, it had become difficult to govern and rife with problems, so in A.D. 293, the emperor Diocletian introduced a system known as the tetrarchy. This effectively split the empire into four regions — two of which were ruled by emperors (augustus), and the other two ruled by each emperor's heir (caesar). Constantius (lived 250-306) was named one of these caesars and eventually rose to be augustus in the west. Upon his death in 306, the army declared his son, Constantine, as augustus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Constantine took control of the western half of the Roman Empire after winning the Battle of Milvian Bridge in A.D. 312 against Maxentius, a rival claimant for the western throne. Legends told during Constantine's lifetime say that before the battle, Constantine had some sort of religious experience that resulted in him warming to Christianity. In A.D. 324 Constantine became emperor of the entire Roman Empire after winning the Battle of Chrysopolis in what is now Turkey against Licinius, the emperor in the east.

Constantinople was built on the site of Byzantium, an urban center that had a long history of prior occupation

With the empire reunited, Constantine brought in a number of important changes that laid the foundations for the Byzantine Empire.

"The most significant of these changes were the emergence of Christianity as the favored (and then the official) religion of the state, and the creation of Constantinople as the new urban center of the empire on the shores of the Bosphorus, midway between all the empire's frontiers," Gregory noted.

Constantinople was built on the site of Byzantium, an urban center that had a long history of prior occupation. The writer Sozomen, who lived in the fifth century A.D., claimed that Constantine's choice of location for his new city was inspired by God — with God supposedly appearing before Constantine and directing him to build the city where he did.

Gregory noted that Constantine was baptized shortly before his death in A.D. 337. Constantine's death led to a series of short-lived successors. Theodosius I was the last sole Roman emperor. After his death in A.D. 395, the empire was split into two empires — east and west.

The fifth century would mark the end of the western half of the Roman Empire. After losing territories to so-called "barbarian" groups and being plagued with infighting, the Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476 when its last emperor was forced to abdicate.

The Eastern Roman Empire, in contrast,survived, becoming what we today call the "Byzantine Empire," although its people still considered themselves "Romans."

Justinian I

Justinian I became emperor in 527. He was the nephew and adopted son of Justin I, who had been a palace guard before usurping the throne in 518. While many historians say that Byzantium's golden age occurred during his reign, Justinian's rule didn't start off very promisingly.

Chariot races were hugely popular at the time and were entwined with imperial power

Early in his reign, Justinian moved to further cement Christianity as the official religion of the Byzantine Empire. By the time of his accession to the throne, traditional Greco-Roman religions had been largely banned. Justinian expanded this by closing the philosophical school at Athens in 529, a place where students learned about the works of ancient Greek philosophers, such as Plato, who had followed traditional Greco-Roman religions.

In 532, just five years into his rule, Constantinople was hit by the Nika riots (Nika means "victory" or "conquer" in Greek). The ancient writer Procopius (who lived in the sixth century A.D.) wrote that Constantinople, along with other imperial cities, was split into two factions — the "Blues" and the "Greens" — which tended to take out their rivalry at chariot races and other events. Chariot races were hugely popular at the time and were entwined with imperial power: Justinian himself was a "Blue," author James Grout wrote in the Encyclopaedia Romana.

Prior to the unrest, Byzantine authorities arrested several members of both factions and sentenced them to be executed. This provoked supporters of the Blues and Greens, who were also angry at the high taxes Justinian had imposed. When the factions' demands for the release of the arrested members were ignored, they united and tried to overthrow the emperor.

The "members of the two factions conspiring together and declaring a truce with each other, seized the prisoners and then straightway entered the prison and released all those who were in confinement there … Fire was applied to the city as if it had fallen under the hand of an enemy …" Procopius wrote.(From History of the Wars, I, xxiv, translated by H.B. Dewing, Macmillan, 1914 through the Fordham University website).

The riots lasted several days, and Justinian had to call in troops to put down the rioters. (Procopius wrote that 30,000 people were killed as a result.) The riots caused widespread damage, but Justinian took advantage of the situation to build something grand. At the site of a destroyed church called the Hagia Sophia (meaning "Holy Wisdom") he ordered a new, far grander cathedral to be built.

After [the Hagia Sophia] was built... Justinian is said to have remarked, "Solomon, I have outdone thee."

"Hagia Sophia's dimensions are formidable for any structure not built of steel," Helen Gardner, an art historian, and Fred Kleiner, a professor of art history at Boston University, wrote in the book "Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History" (Cengage Learning, 2015). The replacement cathedral " is about 270 feet [82 meters] long and 240 feet [73 meters] wide. The dome is 108 feet [33 meters] in diameter and its crown rises some 180 feet [55 meters] above the pavement," they wrote.

After it was built, around 537, Justinian is said to have remarked, "Solomon, I have outdone thee." This quote is first mentioned by writers centuries after the Hagia Sophia was built and may be apocryphal. The cathedral's great baptistry, which may have recently been uncovered by archaeologists, was the place where many Byzantine emperors were baptized.

In addition to building an incredible cathedral, Justinian oversaw a major territorial expansion of the empire, winning back territory in North Africa, Italy (including Rome) and parts of Western Europe.

The intellectual achievements of Justinian's reign were also significant. "Art and literature flourished under his rule, and his officials carried out a remarkably thorough synthesis of Roman law that has served as the basis of the legal systems of much of Europe up to the present day," Gregory wrote.

These achievements happened despite the fact that Justinian provided little direct support for art or literature, wrote Filippomaria Pontani, a professor at the Ca' Foscari University in Venice, in the book "History of Ancient Greek Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the End of the Byzantine Age" (Brill, 2020).

"The long reign of emperor Justinian (527–565) witnessed a remarkable flourishing of poets, jurists, architects and historians," but "the direct patronage of Justinian in the specific field of letters was in fact rather limited," Pontani wrote. Additionally, a large-scale burning of books deemed to be "pagan" occurred in 562, Pontani noted.

In 541 to 542, a plague tore through Justinian's empire and even inflicted the emperor himself, although he survived. However, "many of his compatriots did not, and some scholars have argued that as much as one-third the population of Constantinople perished," Gregory wrote, noting that the disease would re-occur roughly every 15 years from that moment into the seventh century.

A food shortage brought about by cooler weather conditions occurred around the same time making matters worse. Research suggests that a piece of Halley's comet smashed into Earth in A.D. 536, which pushed so much dust into the atmosphere that the planet cooled considerably. It has also been suggested that a volcanic eruption in El Salvador contributed to this cooler climate.

The Byzantine Dark Age

Justinian I died in 565. The centuries after Justinian's death are sometimes referred to as the Byzantine "Dark Age," as a series of misfortunes befell the empire.

In the west, much of the territory that Justinian had captured was lost. By the beginning of the seventh century, "much of Italy was under Lombard rule, Gaul was in Frankish hands and the coastal regions of Spain, the final acquisition of Justinian's re-conquest, were soon to fall to the Visigoths," Andrew Louth, emeritus professor of Patristic and Byzantine Studies at Durham University, wrote in a chapter of the book "The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire" (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Louth noted that between 630 and 660, much of the empire's eastern territory, including Egypt, was conquered by Arab kingdoms, notably such as the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates. This significantly weakened the Byzantine position. "This radical upheaval, together with the persistent aggression of the Arabs against the remaining Byzantine lands and the incursions of Slavs and peoples hailing from the central European steppe into the Balkans, accelerated the transition of the cities of the eastern Mediterranean world that was already well underway," Louth wrote.

"By the end of the (seventh) century the cities had lost much of their social and cultural significance and survived as fortified enclaves," as well as markets, Louth added. "Even Constantinople barely survived, and did so in much reduced circumstances."

Recent research has uncovered evidence that even trash-disposal services were stopped in some Byzantine cities; archaeologists found that it came to an end at Elusa, in Israel, during the mid-sixth century.

These difficult times perhaps contributed to the iconoclasm that occurred in the eighth and ninth centuries in the Byzantine Empire. During this period, much Byzantine religious artwork was destroyed.

Byzantine comeback?

Byzantium never returned to the "golden age" it had experienced during Justinian's rule. Nevertheless, the military situation stabilized in the ninth century, and by the 11th century, Byzantium had regained a considerable amount of territory that it had lost.

By the time of Emperor Basil II's death in December 1025, after a reign of almost 50 years, Byzantium was "the dominant power of the Balkans and Middle East, with apparently secure frontiers along the Danube, in the Armenian highlands and beyond the Euphrates," Michael Angold, professor emeritus at the University of Edinburgh, wrote in another chapter of "The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire." Additionally, the Byzantines succeeded in spreading Christianity to Russia.

However, this comeback of sorts was tenuous to say the least. "Fifty years later, Byzantium was struggling for its existence. All its frontiers were breached," Angold wrote. By this time, nomads were entering Turkey and the Danube provinces, while the Normans had seized the Byzantine Empire's Italian territories.

Nevertheless, the empire eventually regained some semblance of stability once again and continued on.

The Great Schism of 1054

On July 16, 1054, a papal legate (representative) named Humbert of Silva Candida excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople Michael I Cerularius. At the time Pope Leo IX had recently died and a new pope had not been selected. The patriarch refused to relinquish power and excommunicated Humbert in return. This resulted in a schism breaking out between the church at Constantinople and the church in Rome.

Michael I Cerularius had brought in rules stating that all churches in Constantinople should follow Greek customs — even those whose worshippers had many members from western Europe, wrote Philip Kennedy, a Senior Research Fellow in theology at Mansfield College at the University of Oxford in his book "Christianity: An Introduction" (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011). This annoyed Pope Leo IX who sent legates led by Humbert to Constantinople with a letter of protest against his actions. Cerularius refused to meet these legates and after Pope Leo IX died Humbert decided to excommunicate Cerularius wrote Kennedy.

A number of differences in customs had built up between western churches and Greek churches over the centuries. For instance the churches in Rome used unleavened bread whereas the Greek churches tended to use leavened bread. There were also differences in how the Nicene Creed — a statement of faith — should be worded. There were also differences in priestly celibacy — with Greek churches allowing married priests.

Kennedy noted that in the early 11th century when the Normans invaded Sicily they forced Greeks living on the island to adopt religious customs used in Rome, something that annoyed church officials in Constantinople including Cerularius.

The Fourth Crusade

In 1204, an army of crusaders from the west sacked Constantinople and installed a short-lived line of rulers.

The idea of Christians crusading against other Christians was strange even by the standards of the Middle Ages. There are a number of reasons why it came to this. The Great Schism of 1054 and the subsequent decades of separation between the Orthodox Church and the church in Rome was a significant factor, wrote John Giebfried, an assistant professor of history at East Georgia State College and Kyle Lincoln, a special lecturer at Oakland University, in their book "The Remaking of the Medieval World, 1204 The Fourth Crusade" (University of North Carolina Press, 2021). Another important factor is that people from the west were massacred in Constantinople in 1182, Giebfried and Lincoln wrote.

This meant that in 1203, a number of cash-strapped crusaders who were looking for money to finance a military expedition to Egypt were willing to hear out Alexius Angelos, a claimant to the Byzantine throne who encouraged the crusaders to journey to Constantinople.

Alexius Angelos promised the crusaders that if "they helped to reinstate him in Constantinople he would pay them 200,000 marks, give them all the supplies they needed and provide an army of 10,000 men. He would also place the Greek Orthodox Church under the authority of the papacy," Jonathan Phillips, a professor at the Royal Holloway University of London, wrote in an article in History Today in 2004.

Phillips noted that by this time, the Byzantine military was in bad shape. "The death of Emperor Manuel Comnenus (1143-80) presaged a series of regencies, usurpations and coups. Between 1180 and 1204 no fewer than fifty-eight rebellions or uprisings took place across the empire."

The crusaders succeeded in taking Constantinople in 1204;, they sacked the city and installed a new line of "Latin" kings from the west on the Byzantine throne. These rulers would remain in place until a Greek general named Michael Palaeologus re-took Constantinople and crowned himself Michael VIII in1261 (he went on to rule until 1282).

The end of the Byzantine Empire

While Constantinople was once again under control of a Greek ruler, its end was drawing near. The empire struggled on into the 15th century, but the emperors gradually lost their importance in favor of religious officials.

In 1395, Patriarch Anthony, the Patriarch of Constantinople, felt the need to give a speech explaining why the Byzantine emperor was still important. "The holy emperor has a great place in the church, for he is not like other rulers or governors of other regions. This is so because from the beginning the emperors established and confirmed the [true] faith in all the inhabited world…" he said.(From the book Byzantium: Church Society, and Civilization Seen through Contemporary Eyes, University of Chicago Press, 1984, through Fordham University website)

In 1453, the Ottoman Empire, which had been expanding into Byzantine territory since the 14th century, besieged and captured Constantinople, putting an end to the Byzantine Empire. Today, although the Byzantine Empire is long gone, the city of Constantinople (now called Istanbul) flourishes and is still regarded as a crossroads, both literally and metaphorically, between Europe and Asia.

This article was updated on May 10, 2022, by Live Science contributor Owen Jarus.

Additional resources

The Byzantine Empire's warriors fought many battles. Read about the discovery of a 14th-century soldier whose fractured jaw had been healed with gold thread. You can also learn about some rare 1,000-year-old Byzantine swords in this article. Some examples of Byzantine era shipwrecks can be seen in this photo gallery.

Bibliography

Geanakoplos, D. (1984) "Byzantium: Church Society, and Civilization Seen through Contemporary Eyes" University of Chicago Press

Theotokis, G, and Meško, M. (eds) (2021) "War in Eleventh-Century Byzantium" Routledge, 2021

Gregory, T. (2010) "A History of Byzantium" Wiley-Blackwell

John Giebfried and Kyle Lincoln "The Remaking of the Medieval World, 1204 The Fourth Crusade" University of North Carolina Press, 2021

Kennedy, Philip "Christianity: An Introduction" Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011

Phillips, J. (2004) "The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople" History Today, 54, 5

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/crusades/fourth-crusade-and-sack-constantinople

Piltz, E. (2005) "Byzantium in the Mirror: The Message of Skylitzes Matritensis and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople" British Archaeological Reports

Pontani, F. "History of Ancient Greek Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the End of the Byzantine Age" Brill, 2020

Shepard, J. (ed) "The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire" Cambridge University Press, 2008

Timeline

October 312 Constantine I is victorious at the Battle of Milvian Bridge and becomes emperor of the western half of the Roman Empire.

324 Constantine wins the Battle of Chrysopolis and becomes the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. After this Byzantium (later renamed Constantinople) is built up as a second capital of the Roman Empire.

337 Constantine dies, shortly after converting to Christianity.

395 Theodosius I, the last emperor to control the entirety of the Roman Empire, dies. After this the split between the western and eastern half of the Roman Empires becomes permanent, with Constantinople the capital of the eastern half.

476 The Western Roman Empire collapses and its last emperor is deposed."

527 Justinian becomes emperor of the Byzantine Empire.

532 The Nika riots lead to widespread destruction in Constantinople. In their wake Justinian starts the construction of the Hagia Sophia.

536 Temperature cools around this time, possibly as a result of a volcanic eruption or collision with a piece of a comet.

537 The Hagia Sophia is completed around this time.

541/542 Plague tears through the Byzantine Empire; up to one-third of the population of Constantinople dies .

565 Justinian dies. The years following his death are sometimes considered to be the Byzantine Dark Age, as the empire's territory decreases and its power weakens.

630-660 Arab invasions result in the loss of Egypt and Levant.

1025 Death of Emperor Basil II. By this time the Byzantine Empire has stabilized and regained territory in the Balkans and Middle East

1054 The Orthodox Church breaks away from the Roman Catholic Church, creating a religious schism between the Byzantine Empire and western Europe.

1182 People from western Europe who are living in Constantinople are massacred.

1204 The Fourth Crusade results in the crusaders from the west sacking Constantinople and installing a short-lived line of rulers.

1259 A Greek general named Michael VIII retakes Constantinople and establishes himself as emperor.

1395 Patriarch Anthony gives a speech explaining why the Byzantine emperor is still important. The Byzantine Empire's territory and influence has greatly weakened by this point.

1453 The Byzantine Empire comes to an end as Constantinople is captured by an Ottoman army.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus