Ancient Palace's Painted Floors Display Bronze-Age Creativity

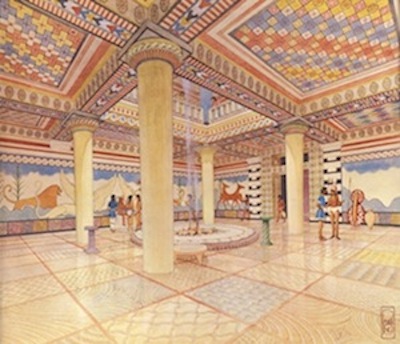

The brightly patterned floors of an ancient Greek palace were painted to mimic patchworks of textiles and stone masonry — an innovative way that Bronze Age artists decorated palatial rooms, a new study finds.

Emily Catherine Egan, a doctoral student at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio, studied the floor of the Throne Room at the Palace of Nestor, one of the best-preserved palaces of Mycenaean Greece, a civilization from the late Bronze Age. She found that the floors of the palace, located in the present-day Greek town of Pylos, were made of plaster, and were often painted with grids of bright patterns or marine animals.

The creative decorations show how ancient Mycenaean artists used floors — together with painted ceilings and walls — to impress palace visitors, Egan said. [History's 10 Most Overlooked Mysteries]

"Mycenaean palatial floor paintings are typically believed to represent a single surface treatment — most often, cut stone or pieced carpets," Egan said in a statement. "At Pylos, however, the range of represented patterns suggests that the floor in the great hall of the palace was deliberately designed to represent both of these materials simultaneously, creating a new, clever way to impress visitors while simultaneously instructing them on where to look and how to move within the space."

The Palace of Nestor's painted floors date back to between 1300 B.C. and 1200 B.C., according to archaeologists. The Throne Room's floor recalls both patterns of painted stone masonryand depictions of textiles in Greek wall paintings, Egan said. The intricate motifs, and the combination of the different patterns, were likely designed by the artist to express the sheer power of the monarchy, she added.

"It depicted something that could not exist in the real world: a floor made of both carpet and stone," Egan said. "As such, the painting would have communicated the immense and potentially supernatural power of the reigning monarch, who seemingly had the ability to manipulate and transform his physical environment."

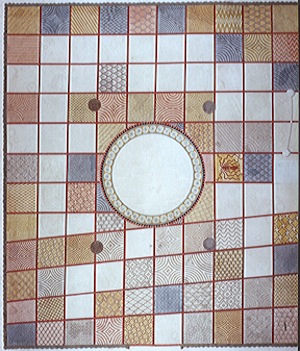

Egan also found evidence that a drafting technique called an "artist's grid" was used to paint the floor. This technique involves laying down a faint grid on the surface to help ensure accurate spacing for repeating patterns or designs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This find is particularly exciting because it solves a long-standing riddle," Egan said. "When first excavated, these mini grids were tentatively identified as functional elements of the room — marking out places for dignitaries to stand on occasions of state. My restudy of the grids, however, now shows that they were artists' tools, providing us with important new information about how the painted floor was designed and constructed."

Egan presented her findings at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, held Jan. 2-5 in Chicago.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.