(ISNS) -- A new medical test that looks for rare cells circulating in the blood could help identify patients at high risk of heart attacks, according to a new study.

The technique, which is detailed in the current issue of the journal Physical Biology, works by measuring circulating endothelial cells in a patient's bloodstream. These cells normally line the interior of blood vessels.

The ability to "measure and characterize [endothelial cells] in the blood of specific patient populations is a beautiful way of diagnosing disease and early intervention," said study co-author Peter Kuhn, a cell biologist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

Endothelial cells can come loose and get circulated in the blood when diseased plaques — buildups of cholesterol that can lead to blood clots — rupture and ulcerate during a heart attack, also known as a myocardial infarction, which can cause inflammation in the arteries.

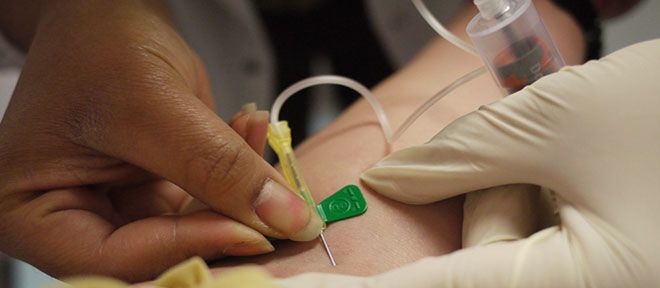

Kuhn and his team used the test they developed, called the High-Definition Circulating Endothelial Cell assay, to detect and characterize endothelial cells in the blood samples of 79 patients who had experienced a recent heart attack. The assay is painless and requires only a blood sample, which can be obtained using conventional techniques.

The team also used the assay on two control groups, which consisted of 25 healthy patients and seven patients undergoing treatment for vascular disease.

The test successfully identified circulating endothelial cells by their morphological features and their reactions with specific antibodies, or proteins produced by the body's immune system. The test showed that endothelial cell levels are significantly elevated in the blood of heart-attack patients compared to the healthy controls.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team's data suggests that healthy individuals have fewer than one endothelial cell in a millimeter of blood. "Patients with heart attacks have on average more than 20 [endothelial cells] in a milliliter of blood," said Kuhn.

Ulrika Birgersdotter-Green, a cardiologist at the University of California, San Diego, said she could envision an assay based on circulating endothelial cells as a biomarker could become a good additional tool for diagnosing myocardial infarctions.

“A good biomarker needs to be reproducible, easy to obtain, and accurate. From what I can tell, this particular assay meets those requirements,” said Birgersdotter-Green, who was not involved in the study.

Whether doctors adopt the new assay will also depend on the turnaround time for results, she added. “If you get the results back quickly, then I think this could be a really nice additional tool” for diagnosing myocardial infarctions, Birgersdotter-Green said.

Kuhn said the test currently requires a few hours for results — sufficient for an overnight turnaround time — but that he believes that duration could be shortened.

“The industrialization of the assay is really what will drive turn around times to where these need to be clinically,” he said.

Kuhn and his team also hypothesize that circulating endothelial cells might be created during the plaque rupturing process that leads up to heart attacks. If their hunch is correct, then their assay could prove to be a valuable "pre-heart attack" test for identifying patients who are at risk of suffering a heart attack, but have not yet experienced one.

This would distinguish it from other tests that look for "post-heart attack" biomarkers in the blood such as tropinins, proteins that are released when heart muscles become damaged.

"The next study now needs to focus on patients at risk to see how predictive [the new test] is," Kuhn said.

The goal "is to predict heart attacks in patients who are at risk, those that show up in the emergency room with chest pain but don't have a diagnosis yet."

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics. Ker Than is a freelance writer living in Northern California. He tweets at @kerthan.