Ultrasound May Boost Brain Performance

Ultrasound may improve sensory perception, according to a new study in humans.

By directing ultrasound to a specific brain area, researchers were able to improve people's ability to discriminate between sensory inputs. Ultrasound is sound far above the upper limit of what humans can hear. It's useful in medical imaging. Doctors and technicians send bursts of ultrasound through tissue and record the echoes, creating a picture of what's inside — whether it's an injured knee or a fetus in utero.

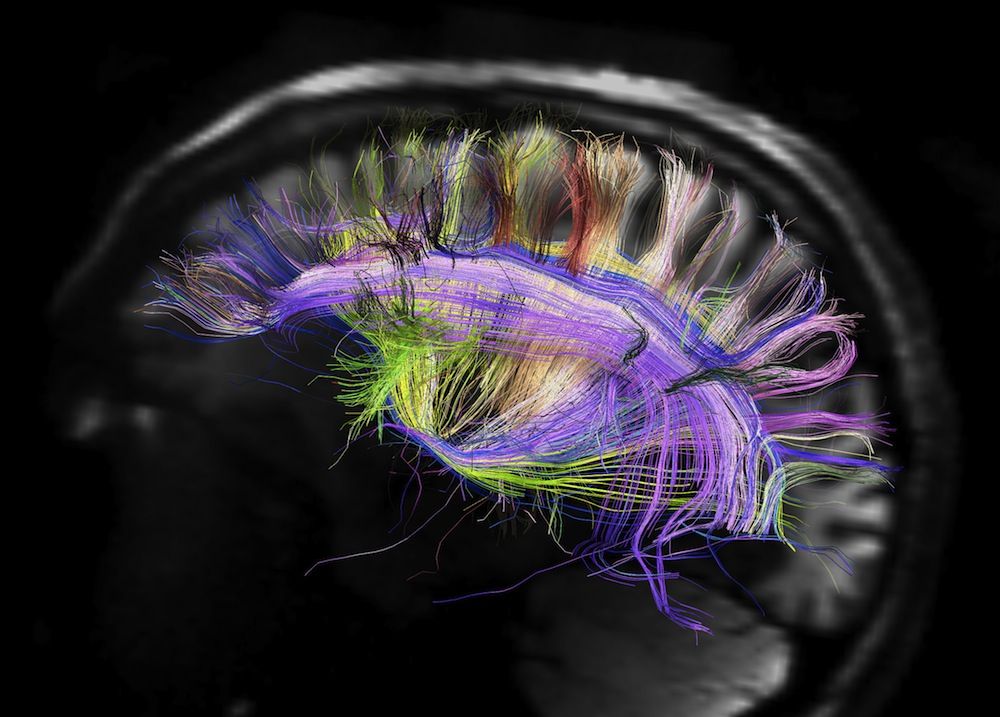

Ultrasound also has potential for mapping the connectivity of the brain. Neuroscientists are particularly interested in understanding how brain areas chat with one another; in fact, a new federal project, the BRAIN Initiative, has the goal of mapping the healthy human brain. [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

Ultrasound is one of several noninvasive methods that stimulate the brain. Another is transcranial magnetic stimulation, which stimulates the brain with magnets. A third is transcranial direct current stimulation, which uses electrodes to deliver a weak electrical current to the brain through the scalp.

The new study suggests that ultrasound may be the best of the bunch.

"We can use ultrasound to target an area of the brain as small as the size of an M&M," study researcher William Tyler, a neuroscientist at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, said in a statement. "This finding represents a new way of noninvasively modulating human brain activity with a better spatial resolution than anything currently available."

Surprising improvement

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tyler and his colleagues focused on sensory perception from the hand. They first placed an electrode on the wrist, over the nerve that carries impulses from the hand to the brain. Using a small electrical current, they stimulated that nerve while focusing ultrasound on the brain region that processes the nerve's signals.

The researchers recorded the participants' brain responses with electroencephalography (EEG), electrodes on the scalp that measure the electrical activity of the brain. The ultrasound weakened the brain waves that encode the tactile stimulation, they found.

But the next set of experiments revealed something truly strange.

The researchers conducted two tests of sensory perception. In the first, participants feel two pins against their skin and must distinguish whether they are being touched at one or two points. The closer the pins are to each other, the harder the task. In the second, researchers blow a series of air puffs against the participants' skin, and they must determine how many individual puffs they feel. The faster the puffs, the harder they are to discriminate.

Instead of these weak brain signals translating to poorer sensory perception, people's performance actually improved on both tests.

"Our observations surprised us," Tyler said. "Even though the brain waves associated with the tactile stimulation had weakened, people actually got better at detecting differences in sensations."

Tweaking the brain

What might explain this seeming paradox? The answer might have to do with how neurons function. When brain cells communicate, they can urge their neighbors to become active (excitation) or tell everyone to quiet down (inhibition). The ultrasound may have affected the brain region's balance of excitation and inhibition, Tyler said.

As a result, the excitation impulses may not have spread so far, essentially giving the brain a better triangulation of where the sensory inputs were coming from.

The boost in sensory perception vanished when researchers moved the ultrasound's focus just a half inch (1 centimeter). That means the method is a fine-grained way to "tweak" brain circuits, both to map their activity and potentially to treat brain disorders.

"In neuroscience, it's easy to disrupt things," said Tyler. "We can distract you, make you feel numb, trick you with optical illusions. It's easy to make things worse, but it's hard to make them better. These findings make us believe we're on the right path."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.