Thanks Academia, Soon I Will Join a Generation of Jobless PhDs (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

My friend leaned forward over the table where we were having dinner. It was a loud, busy restaurant, but she lowered her voice conspiratorially and her eyes took on a sheen of excitement, tinged with fear. “I accepted a position working with a non-profit in the South American rainforest after I graduate, but I haven’t told my professor yet. If I already have a job lined up, he can’t stop me, right?”

At first I considered this apprehensive attitude to be unique and maybe unwarranted. Why wouldn’t a PhD student want to tell her professor, with whom she works so closely and who supervists her PhD, about such a unique job opportunity? But over time, I saw this scenario again and again, and not without reason. Classmates were told they would not be allowed to pursue non-academic opportunities. Professors scorned the idea of being a “bench monkey” at a private biotech company. Internship programmes advertised to us during our PhD interviews were quickly retracted and made to disappear as soon as any real interest was shown.

After entering a PhD programme, it became obvious that when in academia, the only respectable future job is in academia. Becoming an academic is typically considered the holy grail for PhDs in the sciences. Certainly, one can see how the position is an honorable one. To dedicate one’s life to the pursuit of science and discovery, for the sake of knowledge. And with tenure appointment comes the freedom to pursue the answers to the questions you care about, instead of the questions the stockholders of a company care about.

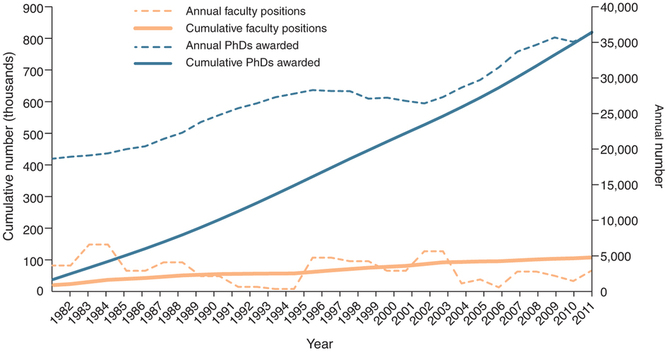

But I have major issues with the view that academia as the be all and end all of science careers. The drive by the US to produce more scientists began around 1940-1950. Spurred by events such as the Manhattan Project and later the space race, increased funding for science and technology drove a perceived need for more scientists. More recently, reports and testimony from the likes of Bill Gates have continued to encourage the production of more scientists. Nevertheless, as numerous recent articles have warned, the population of science PhDs is steadily growing, while the number of available faculty jobs increases at a pace only a snail could envy.

As a result, the competition for faculty positions has become incredibly competitive, and PhDs end up languishing in post-doctoral positions for more than ten years, many never attaining a full-time academic position. Yet, instead of universities taking precautions and educating their students in a way that would provide them with the skills to be competitive in job markets outside of academia, these institutions continue to maintain a traditional instructional framework. While a PhD programme provides experience in skills such as project management, problem solving, and communication, students still come out with a narrow window of extremely specialised knowledge and techniques that are often not transferable to the job market.

What can schools do to produce more well-rounded PhDs? Progress would be to offer courses that train students in a wide variety of skills. This would make them more attractive to potential employers. Additional courses in broader topics such as writing and business would also be beneficial. But classes can only provide limited experience; direct, hands-on training is also vital. Therefore, departments should also provide infrastructure and support that provides opportunities for internships in a range of companies.

With plunges in funding for science research and increases in the number of people earning their PhDs, advances in science may need to come from sources such as private research facilities like Seattle’s Allen Brain Institute. Other groups, such as Microryza and Sage Bionetworks, have started taking advantage of public interest and participation for funding and brainpower. It is becoming clear that traditional research is turning into a broken system.

I think it is time for a change of attitude towards acceptance of non-academic careers. Progress begins with the professors; they must become more open-minded to students’ pursuit of alternate career opportunities. This includes allowing them to devote some of their time to cultivating skills and relationships that will provide a solid foundation upon which to find the right job after graduating. Students, like my aforementioned friend, should not have reservations about discussing their job future with professors.

In the dynamic job market for scientists where there is an increasing amount of competition for fewer academic positions, it is important for both professors and departments to provide support for their students. This includes changing the general attitude towards jobs that are not in academia, and providing programs that give students opportunities to gain skills and experience that will help them have a fulfilling career in science.

What is my next step towards finding my ideal job? Telling my professor I don’t want to be like him…

This article first appeared on Amanda Chung’s blog.

Amanda Chung does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.