Nuclear Attack Aftermath: Make Haste to a Fallout Shelter

People living within about 20 miles (32 kilometers) of a small-scale nuclear attack have up to half an hour to seek out adequate shelter safely, as long as travel time to that shelter is no more than 15 minutes away, according to a recent report on the optimal escape strategies for small-scale nuclear explosions.

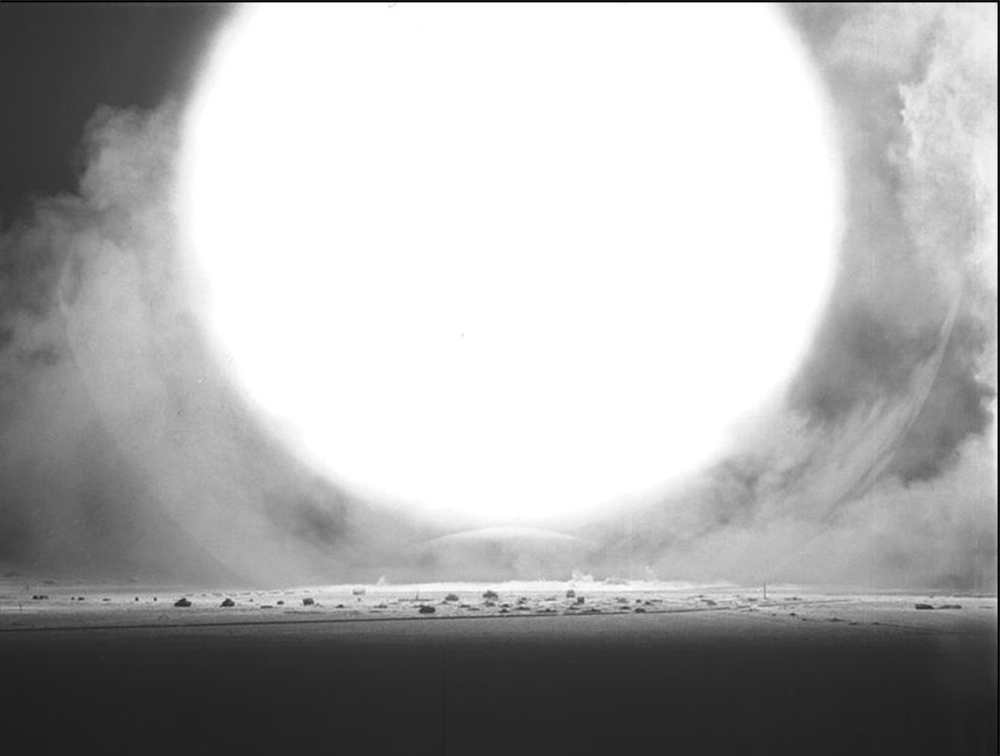

The threats of catastrophic Cold War-style nuclear bombs have subsided since international agreements like the 1970 Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons have taken hold to protect society from the annihilative attacks that flattened Hiroshima and Nagaski, in Japan, during World War II.

Still, the threat of smaller-scale nuclear attacks with explosive energy orders of magnitude less intense has increased in recent years as the technology to build such weapons has become more prevalent. These smaller-scale detonations may not be strong enough to flatten cities, but they do produce harmful radioactive fallout that residents must avoid to reduce the nauseating effects of radiation poisoning and longer-term risks of cancer. [The Top 10 Largest Explosions Ever]

The best way to protect against the radioactive dust and ash of nuclear fallout is to seek shelter underground, but more than 20 percent of U.S. households do not have basements, according to a 2009 survey from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Those people without basements must therefore decide when and how far to travel in search of higher-quality shelter in the event of an attack.

To help simplify this decision process, Michael Dillon of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, Calif., conducted mathematical analyses based on existing data on the threats induced by small-scale nuclear explosions to streamline rules people can abide by to protect themselves from fallout.

"The principle is trying to figure out the least amount of information you need to make your decisions as fast as possible," Dillon told LiveScience. "In these sorts of situations, you don't have a lot of time, and you need to quickly know what you are looking for to make these decisions."

The first order of business is to determine the quality of shelter that one has immediate access to at the time of an attack. Underground concrete shelters are best, as they put the largest amount of mass between a person and fallout, but the core of large buildings — such as large offices or schools — can also provide adequate shelter, Dillon said. Thin-walled homes, on the other hand, made of wood or other flimsy materials are considered poor-quality shelters.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Through his analyses, Dillon determined that people within poor-quality shelters can reduce radiation poisoning by staying within those shelters for only up to 30 minutes after the detonation before seeking out adequate shelter, as long as that shelter is reachable within 15 minutes. However, if adequate shelter is reachable within five minutes, then residents should pick up and go to that shelter immediately after a detonation.

People do not need to do much to protect themselves against radiation while in transit, since the fallout can largely be rinsed off once a person seeks refuge. The only thing a person really needs, Dillon half-joked, is a good pair of sneakers that allows them to travel quickly, if they are traveling by foot.

If traveling by car, people must take traffic into consideration when planning their escape strategies, Dillon said, pointing out that his results provide only one piece of a larger response strategy that can become more complicated by unpredictable factors such as traffic flow.

Dillon is working to assess the distribution of adequate shelters across the United States, and says that his preliminary results suggest that, as a whole, the country is well equipped with adequate shelters within 15 minutes of many households. These analyses are still in the works, however, and are not yet conclusive, he said.

The complete report is detailed today (Jan. 14) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.