Earthquake Shaking Could Be Worse for Vancouver

Vancouver, British Columbia, is one of the handful of major North American metropolises with no damaging earthquakes since modern seismic monitors were invented.

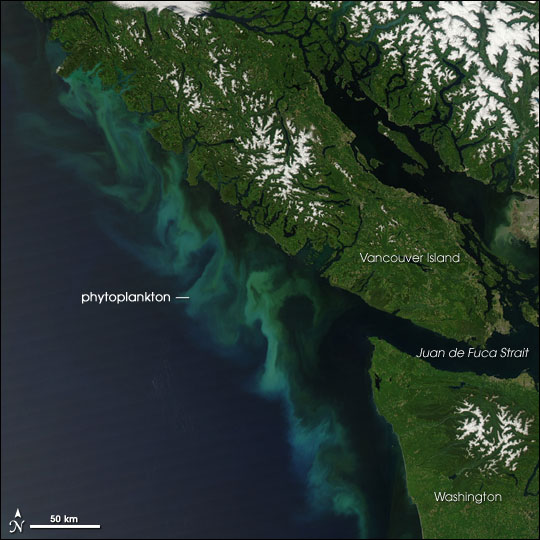

Without an earthquake record to provide insight into how the ground under the city shakes during quake, scientists aren't sure what will happen buildings in the City of Glass when a future earthquake strikes. Recent earthquakes in other cities, such as Christchurch, New Zealand, and Los Angeles, show that damage can concentrate in zones defined by buried geologic structures, such as sedimentary basins (lows or valleys filled by sediment). Basins increase shaking by focusing seismic energy, like a magnifying glass focuses light. Seismic waves can also ping-pong back and forth inside a basin, like waves sloshing inside a swimming pool.

A new study seeks to better understand how the big Georgia Basin surrounding Vancouver will fare in the next earthquake. The Georgia Basin is a shallow, wide bowl filled by silt, sand and glacial deposits. With computer simulations, researchers discovered that the city could see three to four times greater shaking during an earthquake than if the basin wasn't there. The findings were published today (Jan. 20) in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

"This is a worthwhile first step toward building better earthquake-hazard models," said lead study author Sheri Molnar, a seismic geologist at the University of British Columbia.

Vancouver faces a double seismic threat, from both the Cascadia subduction zone, where the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate dives under the North American plate, and closer faults that fracture the Earth's crust.

Molnar and her colleagues discovered that the strongest shaking in Vancouver strikes when earthquakes occur about 50 miles (80 kilometers) to the south or southwest of the city.

"Any earthquake that occurs nearby will be hazardous, but if an earthquake happened farther away (to the south or southwest), we would still see the motion increased because of the geological structures," Molnar told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study is the first time scientists have created a three-dimensional ground-motion model for Vancouver.

"We have a pretty good idea of what kind of earthquakes are likely to occur, but we didn't have a good understanding of how they could generate strong motions in Vancouver," Molnar said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus