In Photos: Mantis Shrimp Show Off Googly Eyes

Crazy Eyes

The peacock mantis shrimp, like this juvenile Odontodactylus scyllarus, are smashing superheroes. The colorful crustaceans have a hammerlike claw that can smash prey with the acceleration of a 0.22-caliber bullet — not unlike Thor's mythological weapon. Turns out, they also have super vision, sporting 12 different types of photoreceptors when four to seven are all that is needed.

Purple-Spotted Mantis

Researchers reporting in the Jan. 24, 2014, issue of the journal Science figure out the mantis shrimp's unique color vision system. Despite the baffling number of photoreceptors, the creatures, like this purple-spotted mantis (Gonodactylus smithii), couldn't easily discriminate between similar colors in a lab experiment.

Baby Peacock Mantis

To account for this seeming lack of superb color vision, researchers suggest mantis shrimp (juvenile peacock mantis shown here) each of their 12 photoreceptors is set to a different sensitivity. That way they can scan objects with all photoreceptors without the need for complex neural processing.

Shrimpy Vision

Unlike human eyes, which are equipped with three types of photoreceptors that send signals to the brain for comparison, mantis shrimp eyes create a pattern that is recognized as a color almost immediately, the researchers find. As such, mantis shrimp like this juvenile peacock mantis, shown here, lose some of their ability to discriminate between colors; even though they may not be able to tell the difference between light orange and dark yellow, for instance, they would easily detect basic colors without having to making comparisons between wavelengths of light in their brain.

Dinner?

Here, a mantis shrimp (Lysiosquillina sulcata) looks at a damselfish (Chrysiptera cyan.).

Near Miss

The mantis shrimp Lysiosquillina sulcata just misses the damselfish Pomacentrus coelestis.

Got It

Score! The mantis shrimp Lysiosquillina sulcata catches the damselfish Dascyllus melanurus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

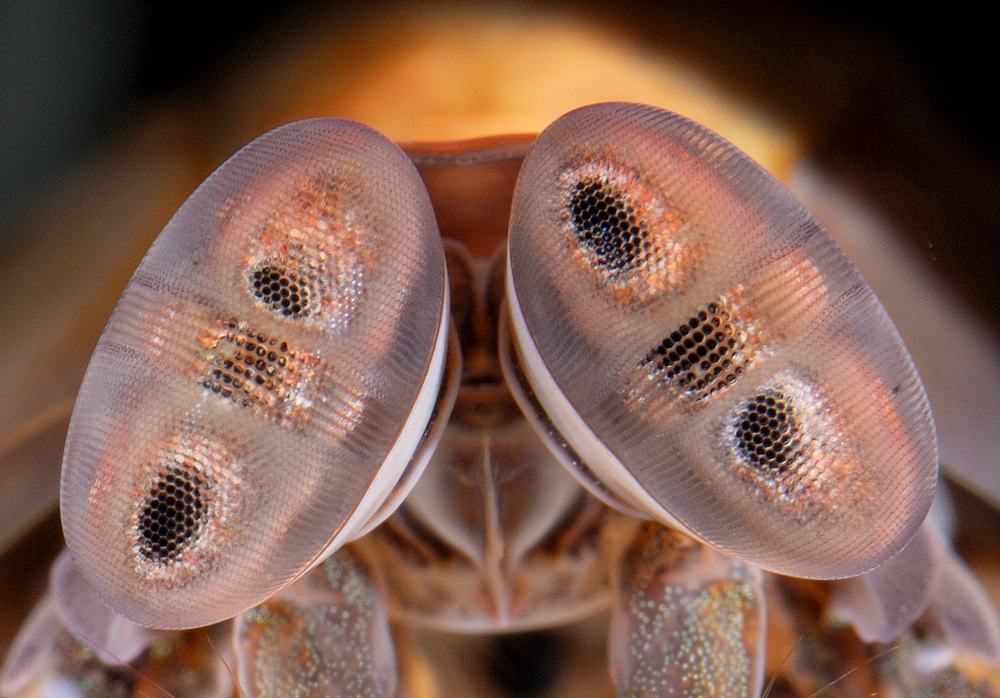

Googly Eyes

The Odontodactylus cultrifer mantis shrimp shows off its amazing eyes. The unique color vision saves the mantis shrimp energy, which they need in the combative world of coral reefs where they live, say researchers.

More Peepers

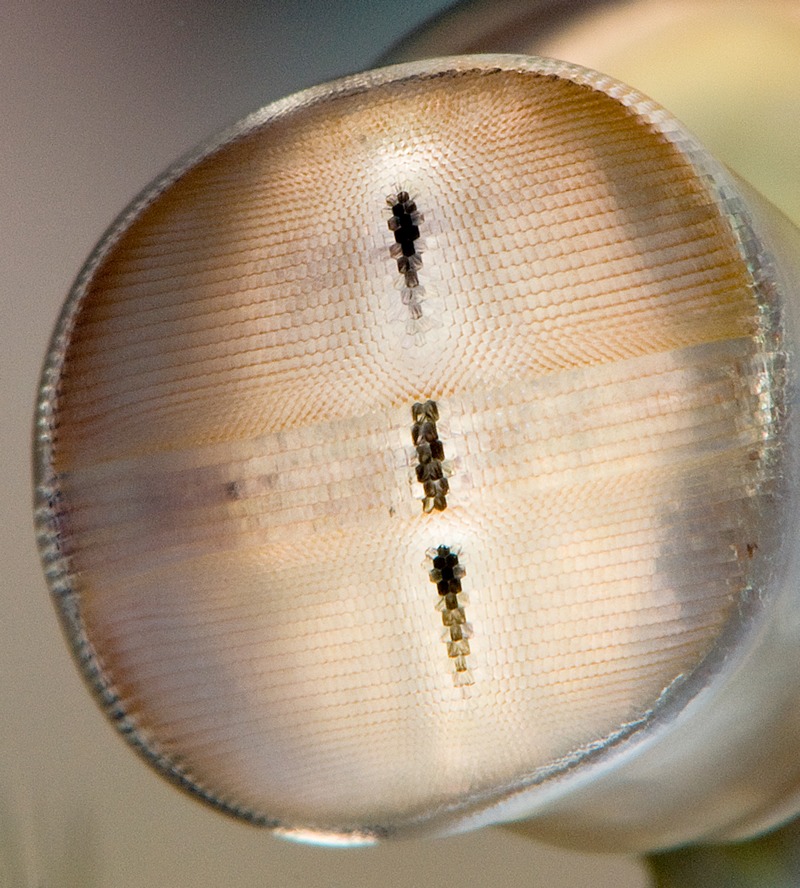

Here, the eyes of the mantis shrimp Pseudosquillana richeri.

Shrimp Eyes

Another look at the eyes of the mantis shrimp Pseudosquillana richeri.

Japonicus Eyes

The eyes of the mantis shrimp Odontodactylus japonicus.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.