Predicting Super Bowl Snow is an Epic Forecasting Challenge (Op-Ed)

Bob Henson is a writer-editor at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR). This Op-Ed was adapted from a post to UCAR's AtmosNews. Henson contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Let's set aside the outcome of upcoming Super Bowl XLVII for a moment — for example, how an offense built around a traditional pocket passer will compare with one that uses a new-school quarterback who can run. Instead, let's look at another critical issue: Will it snow on game day?

Next month's Super Bowl will be the first ever held in an open stadium in the northern United States. As a result, meteorologists, climatologists and almanac writers have been weighing in on what might, could, or will happen weatherwise in New Jersey's MetLife Stadium on February 2.

Most people realize that local weather forecasts become increasingly unreliable more than a few days out. Thus, attempting to predict specific weather a month or two ahead may not be worth the effort, except as a parlor game.

However, once you get to about one to two weeks from kickoff, you're in a more interesting time window — a place where weather forecasts, seasonal predictions and climatological guidance intersect.

So let's consider two questions:

- What can forecasters say today about the weather at East Rutherford, New Jersey, on February 2?

- What might forecasters be able to say in a similar situation years from now? Could research now underway lead to more reliable long-range weather forecasts by the time the next snow-vulnerable Super Bowl takes place?

The big-picture odds

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At Newark Liberty International Airport — the major weather observing site most representative of MetLife Stadium — the average high and low for February 2 are 40°F (4°C) and 25°F (–4°C) The average temperature at 6:00 p.m. EST, just before kickoff time (6:30 p.m.), is 34°F (1°F). Over the period from 1931 to 2013, all but a handful of February 2 dates had 6:00 p.m. readings between 19°F and 51°F (–7 and 11°C). (Much more data can be found at biggameweather.com, a website being operated by the Office of the New Jersey State Climatologist.)

As for the burning question on the minds of millions — will it snow? — the website examines the seven days surrounding February 2 (January 30 to February 5). During this window, at least 0.1 inch of snow has fallen on about 15 percent of all days since 1931. The likelihood of 1.0 inch or more dips to 6 percent, and only about 1 percent of the days have seen more than 6.0 inches. On February 2 itself, the largest snowfall on record is 3.4 inches.

In theory, forecasters could go one step further in certain years by looking to phenomena such as El Niño to see if the climatological odds might shift. In some parts of the country, the presence of El Niño or La Niña can make a given winter more likely to be wetter, drier, warmer or cooler than normal. However, there's no El Niño or La Niña underway this winter, so the point is moot.

Someday, long-range forecasts may be able to factor in the North Atlantic Oscillation, which can also shape the odds of cold and snow across the U.S. Northeast. At the moment, however, the NAO is itself difficult to predict beyond a few days.

The odds in coming days

If you want to go beyond climatology into specific predictions of Super Bowl weather, you'll need to be patient. Forecasts of both local weather and large-scale features have improved steadily over the last few decades, thanks in large part to enhanced data collection by satellites and ever-improving computer forecast models. But beyond more than a week or so in advance, such model guidance should be taken with at least a few grains of salt.

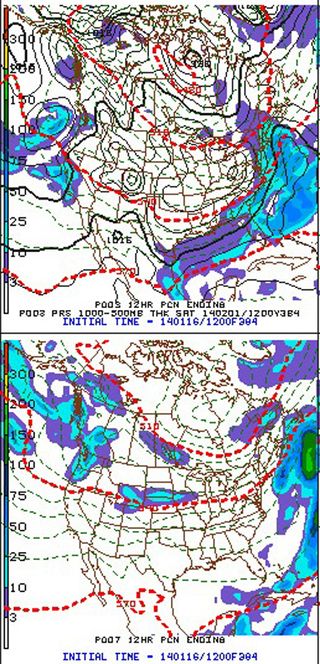

The National Weather Service (NWS) simulates the atmosphere out to 384 hours (16 days) with model runs that are updated four times a day. These feed into the NWS outlooks for 6 days to 10 days and 8 days to 14 days, which include maps depicting the odds that temperature and precipitation will be above or below normal.

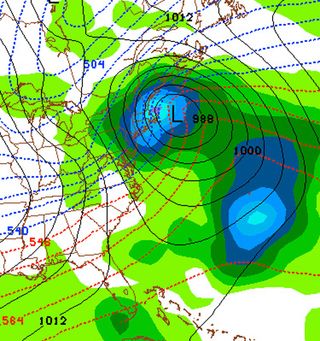

The main tool the NWS uses for extended-range forecasting is the Global Forecast System model. Ominously, the 384-hour GFS forecast of surface weather features based on data from 7 a.m. EST on Thursday, January 16, and valid at 7 a.m. EST on Saturday, February 1, showed heavy precipitation from the New York City area across New England, with temperatures cold enough for snow.

However, there's more to the story. In addition to the "operational" run above, each GFS cycle includes an ensemble of 20 other runs, each at lower resolution (to save on computing time and cost). All are produced at the same time, but with slightly varied starting-point conditions that mimic the uncertainty in our still-limited observations. Typically, the ensemble members start out closely aligned but then deviate from each other within a few days. Members of an ensemble can differ markedly from each other over the long range. Moreover, a new set of ensembles is produced every six hours, and the results can change dramatically from one run to the next. Making matters even more complicated, several other global models are run a few days into the future, each with their own representations of the atmosphere.

This suggests that no one should put too much stock in any single prediction two weeks out. Even the official NWS local forecasts that go out seven days need to be viewed with some caution at the far end, since their skill is little better than climatology at that point.In other words, the average high, low and precipitation amounts observed on February 2 over the last 30 years may come nearly as close to being correct as a typical weather forecast issued seven days beforehand.

It's also important to distinguish between "skill" and "accuracy." One could offer a firm prediction of "no snow" a month in advance of the Super Bowl, and chances are greater than 80 percent that the forecast would be correct — but not necessarily skillful. The chances of snow are less than 50-50 on any given day in February, so climatological averages alone could have given you a similar answer.

On the plus side, ensembles can be useful in suggesting the general patterns that might be present a few days from now, such as whether there will be a tendency toward cold air in the eastern United States. If the ensemble members agree strongly on a given scenario, and if multiple models also agree, it's more likely that the actual pattern will end up resembling that scenario.

As of today (January 22), there is growing agreement that next week will bring a prolonged stretch of cold weather to the Northeast, with the possibility of rain or snow toward Super Bowl weekend. However, the devil is in the details — just a slight shift in the timing or location of key weather features could make a big difference in the result 10 or 12 days from now. That's one reason why long-range local forecasts can still be challenging even when the larger-scale weather features are becoming more clear a few days out.

Weather and chaos

Part of the credit for this state of affairs goes to atmospheric chaos. Its importance was identified by Edward Lorenz, the famed physicist and frequent NCAR visitorbased at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lorenz theorized that weak, random elements in the atmosphere would eventually grow in scope until they dominated any useful signal from a forecast model. At first Lorenz didn't specify the outer range of potentially useful predictions, but later he speculated it might be around three weeks, perhaps a bit less.

Research continues to back up chaos theory, according to Grant Branstator, an NCAR scientist who has studied longer-term forecasting.

"Studies consistently show that in typical situations, one cannot have any skill for predictions of individual days if the predictions are longer than about two weeks," says Branstator. "This is not because models are poor approximations to nature. Even a perfect model would have this limit. This is a physical constraint that anyone attempting to make 16-day predictions cannot ignore."

So, will long-term forecasts ever get better?

Branstator and some colleagues do see a glimmer of hope that at least some useful information can eventually be gleaned two weeks, or more, out from a target date. A recent study led by NCAR's Haiyan Teng offers one example with respect to U.S. heat waves. Teng, Branstator and their colleagues found that if a particular upper-level circulation pattern happens to be unusually strong, then the chances of a Great Plains heat wave occurring two weeks later are greater than normal. If the pattern is four times stronger, then the odds of a significant heat wave are also boosted fourfold, from about 2.5 percent to 10 percent.

"Even under these unusual conditions, when the system may be unusually predictable, we can still only say there is a 10 percent chance of a heat wave," notes Branstator.

Researchers are also looking into another factor that could help improve skill in predictions beyond two weeks: the connection between tropical rainfall and subsequent weather patterns. It may seem like a long-shot to associate showers and thunderstorms over the Indian Ocean with storms over the United States, but scientists are zeroing in on a periodic disturbance, the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) (illustrated in this QuickTime movie). MJO events move from the Indian Ocean across the globe, persisting and affecting weather patterns for weeks at a time.

For example, the approach of an MJO disturbance during hurricane season substantially raises the oddsof a tropical cyclone in the Gulf of Mexico and western Caribbean. And in winter, the onset of an MJO event in the Indian Ocean is associated with the location and severity of major storms on the west coast of North America that occur about 10 days later.

"If you can find out how an MJO event starts, you may get a couple of weeks' warning about wintertime storms in the United States," says NCAR scientist Mitchell Moncrieff, who focuses on long-term forecasting challenges.

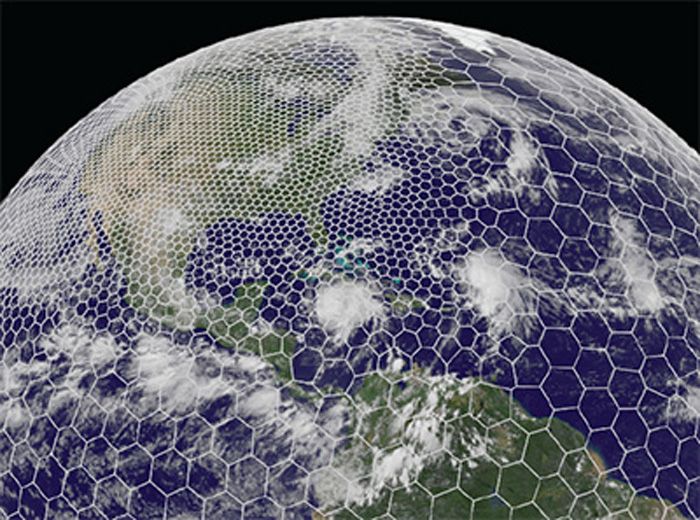

In order to learn more about such atmospheric connections, scientists need better observations and computer simulations. One of the new tools drawing interest is the Model for Prediction Across Scales, developed by NCAR and the U.S. Department of Energy and made available to the research community last year. It enables scientists to run computer simulations of the entire globe while focusing on specific geographic regions. In recent tests, MPAS successfully depicted a cluster of severe Midwest thunderstorms more than four days out, and tropical cyclones in the Pacific up to six days in advance.

Across the community of researchers, there are differing opinions on how much progress can be realistically expected for predictions beyond two weeks. Many scientists warn that even perfect tools would hit a wall of chaos that would render detailed local forecasts meaningless beyond that point. Other researchers assert that it may be possible someday to anticipate some aspects of general weather patterns, at least in a probabilistic sense, more than two weeks out.

"Extending the prediction of weather extremes beyond the two-week range is an international grand challenge," says Moncrieff. "Progress in this area is crucial to help decision-makers prepare for potentially damaging weather events."

What about that football game?

Even if today's long-range models were extremely reliable in terms of the flow of major weather features one or two weeks out, ponder this point: just a half day of error in a forecast for a football game 10 days from now (or only about 5 percent in terms of timing) could spell the difference between sunshine and snow, assuming a fast-moving weather system were in the area. This alone should make us cautious about taking any specific forecast too literally until we get within a few days of an event.

At least through 2018, there are no more Super Bowls scheduled for an outdoor northern stadium. As for the 2014 edition, the National Football League promises that the game will be rescheduled if a forecast of heavy snow materializes. For now, no one can say for sure if that will happen. But at least the climatological odds of just a 6 percent chance of more than an inch of snow should give some warm comfort to fans.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.