Scientists Create Peanut Butter Jellyfish

It's a lunchroom staple and now an aquarium oddity. For some reason, scientists have created the first-ever peanut butter jellyfish.

By blending all-natural creamy peanut butter with saltwater and adding it to the tanks of moon jellies, aquarists at the Dallas Zoo and Children's Aquarium created an "unholy amalgamation of America's favorite lunchtime treat and live cnidarians."

Why? Well, as Deep Sea News reports, the scientists wanted to know if it could be done.

"Whether or not it should be done is a question no doubt to be debated by philosophers for the ages (or at least by some aquarists over beers)," Dallas Zoo aquarist P. Zelda Montoya and aquarium supervisor Barrett L. Christie wrote in the January issue of "Drum and Croaker: A Highly Irregular Journal for the Public Aquarist."

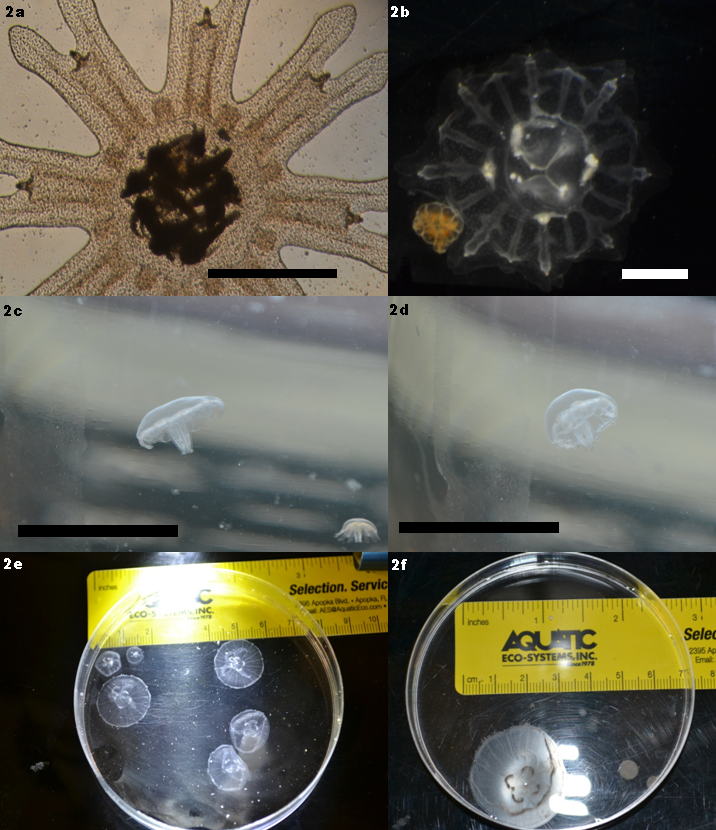

Worry not for the experimental jellies: The scarfed the peanut-butter protein out of their tanks and actually grew about 0.2 inches (4 millimeters) in 8 days. They also took on a brownish hue thanks to "peanutbutterocity," the aquarists wrote. Goofy as the experiment was, peanut butter is a potential source of protein for jellies, fish and other aquarium residents, Montoya and Christie wrote. "We hope this ridiculous experiment illustrates that unconventional approaches in husbandry are at the very least, worth trying once," they wrote.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.