Atrial fibrillation and arrhythmia: Causes, symptoms and treatment

Atrial fibrillation is a heart condition that causes an irregular heart rate. Sometimes, there can be no symptoms.

An arrhythmia, or irregular heartbeat, is a problem with the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat. People with this condition may have a heart that beats too quickly, too slowly or has an irregular rhythm. While it is normal to feel as if your heart skips a beat occasionally, a frequent irregular rhythm may lead to palpitations, dizziness and other symptoms, according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Arrhythmias may occur when there is a problem with the heart's electrical system. In the case of atrial fibrillation, also known as A-fib or AF, the result is that the top chambers of the heart contract irregularly.

"Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia," said Dr. Lawrence Phillips, a cardiologist and assistant professor at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City. "It's caused [by] irregular impulses coming from the top chamber of the heart."

Atrial fibrillation may cause heart disease or worsen existing heart disease, according to the NHLBI. Sometimes it goes away on its own. For others, atrial fibrillation is an ongoing heart problem that lasts for years.

What are the causes of atrial fibrillation?

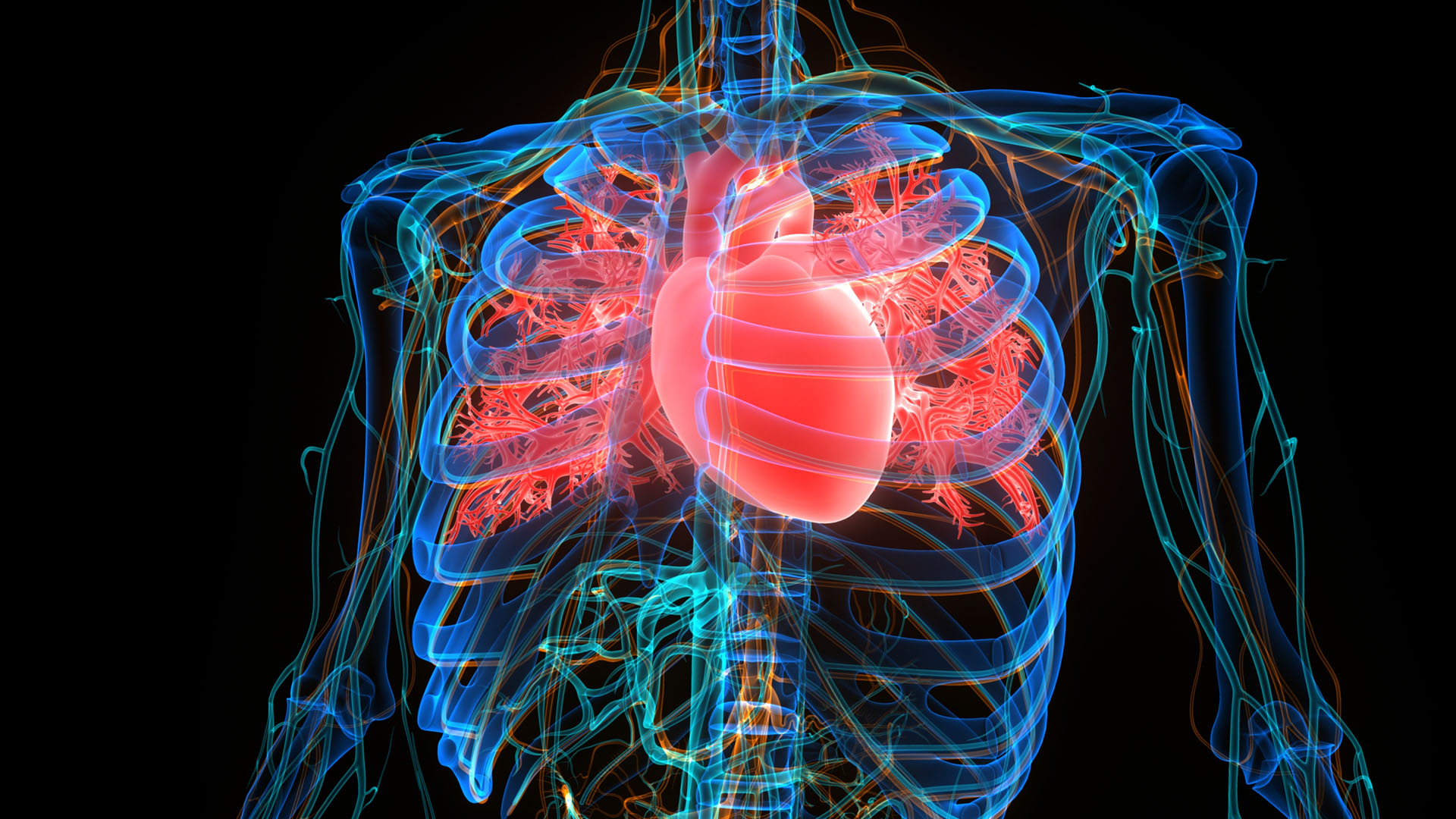

The human heart is made up of four chambers: The left and right atria and the left and right ventricles. The electrical signals that control the heartbeat originate in the right atrium, at a spot called the sinus node. This node pulses out an electrical signal, which spreads from the top of the heart to the bottom, causing the muscle to contract as it travels, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The path of this electrical stimulation is important, as it causes blood to move in the proper direction at the proper time. First, the atria contract, sending blood into the ventricles. Next, the signal hits another node, the atrioventricular node, which slows the electrical pulse slightly so the ventricles can finish filling. Then the electrical signal zips down the ventricles, causing them to contract and squeezing blood out of the heart. Oxygenated blood from the left ventricle goes out to the body's tissues, while deoxygenated blood from the right ventricle goes to the lungs to pick up more oxygen.

This process repeats 60 to 100 times a minute, depending on the person's fitness and pulse rate.

In atrial fibrillation, this electrical signal is disrupted. Instead of spreading normally through the atria, the electrical pulse spreads erratically. "When they beat erratically, it can make the heart go fast," Phillips said. This causes fibrillation, or rapid and irregular contraction.

The erratic signals also arrive at the atrioventricular node in a disorganized way, causing the ventricles to beat faster than normal. The atria and ventricles are now uncoordinated, so that blood doesn't move in and out of the heart efficiently.

Dr. Lawrence M. Phillips is a cardiologist in New York City and is affiliated with multiple hospitals in the area He received his medical degree from Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University and has been in practice for more than 20 years.

However, mounting evidence challenges the traditional understanding of atrial fibrillation as a disease caused primarily by the disruptions within the heart’s electrical system. According to a 2019 review published in the journal Heart, atrial fibrillation can be caused by many different, and often overlapping, factors and medical conditions. These may include electrophysiological and structural changes within the left atrium, genetic factors, as well as disrupted metabolism (for example, elevated blood sugar levels). So far, scientists have found more than 160 genes associated with the condition, according to a 2021 review published in the European Journal of Human Genetics.

Studies have also shown that atrial fibrillation may be triggered or sustained by certain pathological processes, often referred to as nodal points, according to a 2021 review published in the journal Current Opinion in Cardiology. These nodal points may include factors like inflammation, oxidative stress and autoimmune mechanisms, and tend to vary from patient to patient.

What are the symptoms of atrial fibrillation?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), some people who have atrial fibrillation don’t know they have it and don’t have any symptoms. Others may experience one or more of the following symptoms:

- Irregular heartbeat

- Heart palpitations (rapid, fluttering or pounding)

- Lightheadedness

According to the Mayo Clinic, atrial fibrillation may be:

- Occasional (paroxysmal atrial fibrillation): A-fib symptoms come and go, usually lasting for a few minutes to hours. Sometimes symptoms occur for as long as a week and episodes can happen repeatedly.

- Persistent: A-fib symptoms do not go back to normal on its own.

- Long-standing persistent: A-fib symptoms are continuous and last longer than 12 months.

- Permanent: The irregular heart rhythm can't be restored and medications are needed to control the heart rate and to prevent blood clots.

Complications of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation may cause heart disease or worsen existing heart disease. If left untreated, atrial fibrillation can lead to serious and even life-threatening complications, like stroke or heart failure, according to the NIH. Atrial fibrillation may also increase the risk of heart attacks and death due to any cause, according to a 2017 meta-analysis published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Many studies have shown that atrial fibrillation may be linked to cognitive impairment, vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease, according to a 2019 review published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Researchers suggested that A-fib may contribute to cognitive decline by inducing ischemic stroke, reducing blood flow to the brain and increasing the risk of brain damage.

Treatment for atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is treated with blood thinners to reduce the risk of stroke-causing clots, as well as medications that slow the heart rate to a normal level and encourage normal rhythm, Phillips said. Treatments are most effective in patients who have had irregular rhythms for less than six months, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

In some cases, doctors may suggest surgical procedures to treat atrial fibrillation. One common treatment is electrical cardioversion, in which doctors administer a series of low-energy shocks to the heart muscle to nudge it back into rhythm.

Another procedure, catheter ablation, is used to destroy tissues that might be interfering with the heart's electrical signals. "More and more, doctors are performing ablation of small areas of the heart ” to prevent errant signals from being propagated, Phillips said.

In the most serious cases, catheter ablation is used to completely destroy the atrioventricular node.

A final option is an open-heart surgery called maze surgery, which uses small cuts or burns to disrupt the abnormal electrical signals.

More recent studies have also shown that atrial fibrillation can be effectively treated with cryosurgical techniques (freezing and thawing the heart tissues), according to a 2021 review published in the journal The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. Cryotherapy appears to be quicker, safer, and as effective as the standard maze surgery, the review researchers noted.

Additional resources:

- The National Institutes of Health provides more information about atrial fibrillation

- You can find out more about keeping your heart healthy on the American Heart Association website

- More information on heart disease can be found on the Mayo Clinic website

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

- Anna GoraHealth Writer