Ishtar Gate: Grand Entrance to Babylon

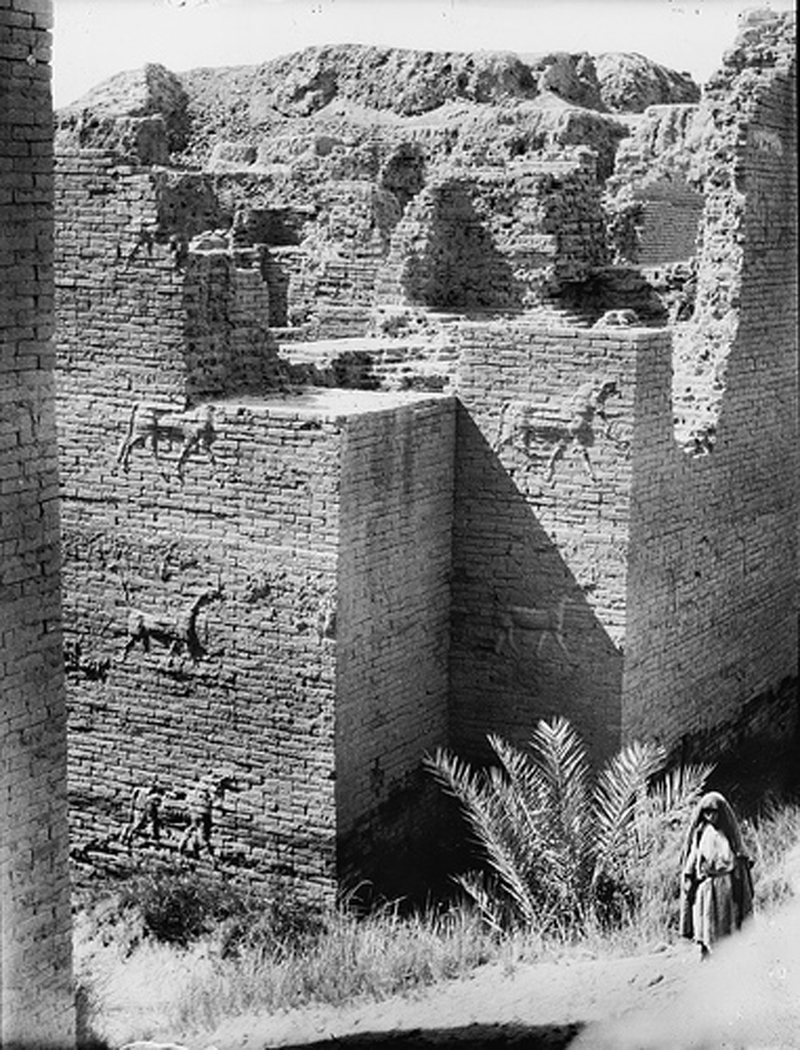

The Ishtar Gate, named after a Mesopotamian goddess of love and war, was one of eight gateways that provided entry to the inner city of Babylon during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (reign 605-562 B.C.). It was decorated with glazed blue bricks that depicted alternating rows of bulls and dragons.

A processional way went through this gateway and was decorated, in part, with reliefs of lions. Every spring a procession that included the king, members of his court, priests and statues of the gods traveled to the “Akitu” temple to celebrate the New Year’s festival.

“The dazzling procession of the gods and goddesses, dressed in their finest seasonal attire, atop their bejeweled chariots began at the Kasikilla, the main gate of the Esagila (a temple dedicated to Marduk), and proceeded north along Marduk’s processional street through the Ishtar Gate,” writes Julye Bidmead, a professor at Chapman University, in her book “The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia” (Gorgias Press, 2004).

The gate was excavated between 1899 and 1917 by a German archaeological team led by Robert Koldewey. After World War I part of the gateway, the smaller antegate, was reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin and is on public display. Additionally, the museum has the remains of the larger inner gate, which rose an estimated 25 meters (82 feet) off the ground from the roadway to the top of its towers, writes Andrew George, a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, in an article in the book “Babylon” (Oxford University Press, 2008). A passageway running 48 meters (157 feet) connected the two gates to form a single double gateway, writes researcher Joachim Marzahn in another article in "Babylon."

“From the top of the gate an observer could see the whole city spread out below them,” George writes. This inner gate was so large that the Pergamon Museum didn’t have room to reconstruct it and its remains are currently in storage.

One name of the gateway was “Ishtar is the one who defeats his enemies” Marzahn writes. George added that the gateway was also called “Ishtar repels her attackers” and eventually it gained the epithet “entrance of kingship” because the gate “was where kings of gods and men together re-entered Babylon in triumph after the symbolic rituals of the Akitu temple.”

The Empire of Babylon

By the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, the city of Babylon had existed for almost 2,000 years and had seen its share of good and bad times. Nebuchadnezzar II came to the throne at a time when Babylon was achieving unparalleled prosperity. By the end of his reign, the city would control an empire that extended, in an arc, from the Egyptian border to the Persian Gulf.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The city’s good fortune meant that Nebuchadnezzar II was able to embark on a building program that would see an older Ishtar Gate torn down and a new one, with blue glazed bricks, constructed. He also built a new processional way that went through the gate.

In the process of constructing the gate and renovating the processional way, and nearby palace, the king’s builders raised the ground nearly 20 meters (65 feet) above its original grade.

“Step by step, the former low-lying gate building and street had been raised some 20 (meters) during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II,” writes Olof Pedersén of Uppsala University in an online article in the journal “Zeitschrift für archäologie und Kunstgeschichte.”

Dragons and bulls

The gateway itself was decorated with glazed blue bricks, which depict alternating rows of bulls and a dragon like creature called “Mušḫuššu.” This creature is the “sacred hybrid” of Marduk, the imperial god of Babylon who had a large temple in the city, and his son Nabu, writes Tallay Ornan of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in a 2005 edition of the journal “Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis.”

“The Mušḫuššu was viewed as a menacing hybrid with leonine features and a snake’s head which spouted two erect horns or a long horn, bent back with a curling end,” she writes. “Its long forked tongue sometimes hung from its mouth or, alternatively, was depicted as if spitting fire.”

She notes that bulls, such as the ones seen on the Ishtar Gate, represented Adad, a storm god in Mesopotamia.

Creating blue glazed bricks

The blue glazed bricks were a challenge to make but were durable and could make an impression on a visitor. They “created glossy and colorful pictures that were capable of withstanding weather,” writes Stephen Bertman, professor emeritus at the University of Windsor, in his book “Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” (Facts on File, 2003).

“The brick was sculpted in low relief before being baked and was then coated with glazes in which pigments were blended with melted silica,” he writes.

Blue was a rare natural color in the Mesopotamian world and the glazed bricks “must have been a really, really, striking appearance to a visitor,” said Royal Ontario Museum curator Clemens Reichel in a video discussing a lion from Nebuchadnezzar II’s throne room which is now in the Toronto museum.

The end of Babylon

In 539 B.C., Babylon would fall to the forces of Cyrus the Great, who incorporated the city into the Persian Empire. About two centuries later, the city would fall again to Alexander the Great, who made it the capital of his own short-lived empire, which collapsed after his death in 323 B.C. Babylon then fell into a period of decline and eventually became abandoned, falling into ruin.

While the Pergamon museum has many remains from the Ishtar Gate and processional way, reliefs can be found in other museums throughout the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. There are also substantial remains present in Iraq, and in 2010 a $2 million conservation grant was given by the U.S. State Department to help preserve the remaining portions of the gate, processional way and nearby ruins. They had sustained some damage in the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq War.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.