Mosquito Sperm Have 'Sense of Smell'

Updated on Feb. 5, 2 p.m. ET.

Mosquito sperm have a sense of smell — a surprising finding that could one day help control disease-carrying mosquitoes, researchers say.

Mosquitoes use scent-detecting molecules known as odorant receptors in their antennae. These sensors help mosquitoes "sniff out" sources of blood as part of their sense of smell, technically known as olfaction.

Now, researchers have discovered mosquitoes have these same molecules in their sperm.

Sperm sniffers

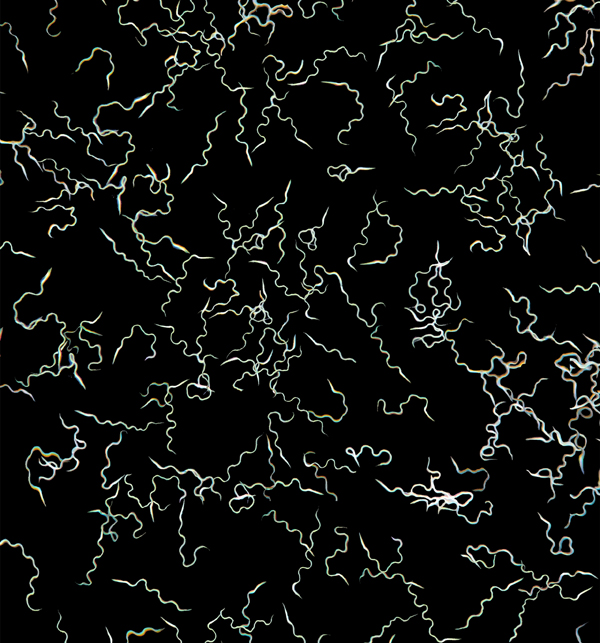

Scientists analyzed the mosquito species Anopheles gambiae, one of the most common carriers of malaria. They found odorant receptors on the whiplike tails of the mosquitos' sperm. These molecules help to spur the beating of the tails, and thus help control the movement of the sperm, the researchers said. [Sexy Swimmers: 7 Surprising Facts About Sperm]

"We know these molecules are very powerful tools for responding to chemical signals from the environment, but this work shows these molecules can also be co-opted to respond to chemicals inside the organism," said study author Laurence Zwiebel, a molecular biologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. In other words, molecules used in one part of the body can be co-opted or diverted for a role elsewhere in the body.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During the process of evolution, successful molecules are often reused after they have arisen. The researchers suspect that odorant receptors may have evolved first in the reproductive system of insects and then were adapted to help form the foundation of the mosquito's complex sense of smell.

"Certainly, reproduction is a much more basic process than olfaction," Zwiebel told Live Science.

Female mosquitoes live for about a month and mate only once. They store the sperm of their mates in special organs called spermathecae. The females then suck blood to get the basic compounds they need to produce eggs. This is why they bite humans and other animals and, in so doing, help spread lethal diseases such as malaria, yellow fever and dengue fever. Once the eggs have developed, they are fertilized by the sperm stored within the female's reproductive tract.

"The sperm may need a chemical signal to become ready for fertilization," Jason Pitts, a researcher at Vanderbilt University, said in a statement. "There are reports that within one day after insemination, the sperm begin swimming around in the spermathecae. There must be one or more signals that activate this movement, and our findings suggest that odorant receptors may be the sensor that receives these signals."

The researchers also found these odor-detecting molecules in the sperm of the yellow-fever mosquito Aedes aegypti, the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis. The researchers said this finding suggests that odorant receptors have a general function in sex across most, if not all, species of insects.

"These molecules help bring sperm and eggs together in insects," Zwiebel said.

These results are similar to recent work that discovered scent-detecting molecules in human sperm. This may represent an intriguing example of convergent evolution — in which different, and perhaps only distantly related, species evolve structures with similar functions, typically to solve similar problems.

Pest control

Future research needs to uncover how important these odorant receptors are in insect reproduction.

"Can insects reproduce in their absence?" Zwiebel said. "Maybe not as effectively, but probably yes. There are a lot of mechanisms acting in parallel in reproduction, so removing one often is not completely detrimental. You can imagine evolution not putting all the eggs in one basket; pardon the pun."

These findings could lead to new ways for people to control insects. For instance, if scientists can use this research to render males sterile, overwhelming numbers of sterile males of a pest insect species can be released into the wild. In the wild, these sterile males can compete with wild males to mate with females, ultimately reducing the numbers of those pests that are born. This strategy has been used to successfully eradicate the screwworm fly from areas of North America and to control the populations of the Medfly and Mexican fruit fly in Latin America.

"Insect control is of major importance not only for disease vectors, but also for agriculture and nuisance insects," Zwiebel said. "I don't think this work will lead to a magic bullet to solve all problems, but if it can bring another tool into the toolbox of insect control, I think that'll be very important."

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 3 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Editor's Note: The image caption was updated to reflect the fact that the mosquito Aedes aegypti does not carry malaria.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.