Black Death Likely Altered European Genes

The Black Death of the 14th century may be written into the DNA of survivors' descendants, new research finds.

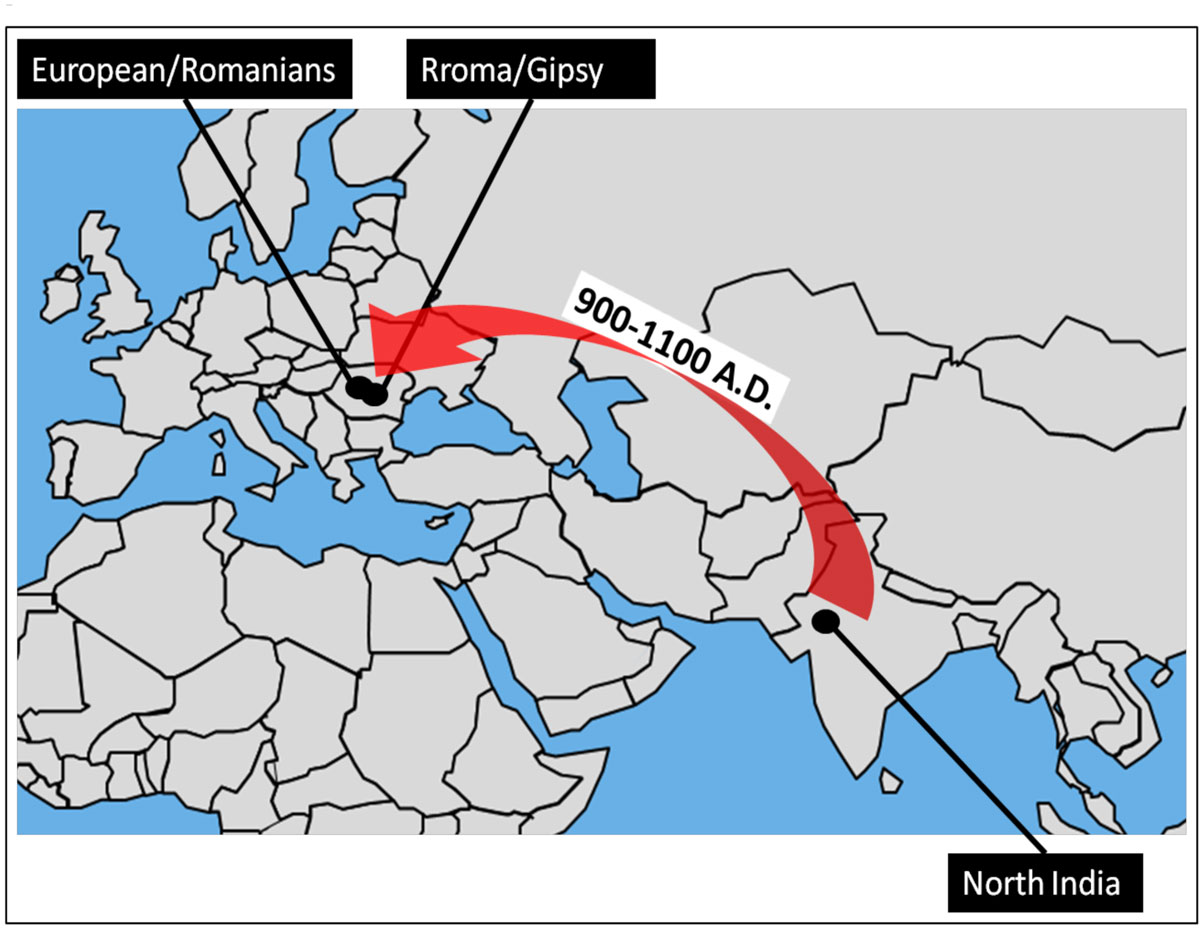

The study reveals that Roma people (sometimes known as gypsies, although this is considered a derogatory term) and white Europeans share alterations to their genetic code that occurred after the Roma settled in Europe from northwest India 1,000 years ago. The plague of the 1300s, which killed at least 75 million people, is a likely candidate for forcing this evolutionary change.

"We show that there are some immune receptors that are clearly influenced by evolution in Europe and not in northwest India," said study leader Mihai Netea, a researcher in experimental internal medicine at Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center in the Netherlands.

"India did not have the medieval plague, as Europe had," Netea told Live Science. "We have also demonstrated that these receptors are recognizing Yersinia pestis, which is the plague bacterium." [In Photos: 14th-Century Black Death Graves Discovered]

Searching for similarities

Netea and his colleagues made their discovery by scanning almost 200,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), or short segments of DNA that vary among people. They tested people from Romania, as well as Roma people. For social and economic reasons, Netea said, the Roma have lived among Europeans since about A.D. 1000, without much interbreeding between the two groups. That gives researchers a rare opportunity to study two genetically distinct populations in one geographical region.

The researchers looked for genetic variations that appeared in both Europeans and Roma people. Then, they took that list and crossed off the genetic variations that also appeared in a population of northwest Indians, to rule out evolutionary change that originated outside Europe.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The result was a list of about 20 genes that show evidence of convergent evolution between Europeans and Roma — meaning the two groups started out different but evolved to look more similar because of pressures in their environment.

Black Death genetics

The genes on the list have a variety of functions. One gene, SLC45A2, is known to be involved in skin pigmentation. Others are linked to immune-system function.

One immune-related cluster included three altered genes, making it the most obvious candidate for closer perusal. The cluster, called TLR2, was already known to be involved in building the receptors on the surface of leukocytes, immune cells that recognize and destroy foreign invaders.

Because plague was such a widespread and devastating event in Europe, Netea and his colleagues reasoned that the Black Death outbreak, which occurred after the Roma arrived, might have put pressure on this gene cluster to evolve. To test the idea, they looked at how cells engineered to express TLR2 would hold up against Y. pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, an ancestor of Y. pestis. They found that TLR2 caused a heightened immune response when exposed to both bacteria.

Other diseases could have altered the same genes, Netea said, but plague is a strong candidate, because it affected Europe and not northwest India, and because it had such a widespread, devastating influence. The findings could have medical implications even in today's world, where plague is no longer such a danger. For example, autoimmune disorders, in which the body attacks its own tissues, may arise because of immune systems programmed by epidemics to respond strongly to the threat of invasion, Netea said.

Humans "were modified, basically, by the infections," he said.

The researchers report their findings today (Feb. 3) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.