Bees' Salt-Sensing Feet Explain Swimming Pool Mystery

The first-ever investigation of the honeybee ability to taste with their front feet may explain a persistent bee mystery: Why they swarm saltwater swimming pools.

Saltwater swimming pools don't require chlorine or other chemicals, but online home and garden forums are full of complaints about these swimming holes' dark side. Apparently, they attract honeybees en masse. Now, scientists find that bees have taste receptors on their feet that are so sensitive to salt, that they even dwarf the bees' capacity to taste sweets.

"Our guess is they may not need to land on the water surface" to taste the salt, said study researcher Martin Giurfa, the director of the Research Center on Animal Cognition at the University of Toulouse in France. "They might just sense, with the tips of the legs, the presence of the salty solution and then decide to land."

The solution to the bee pool mystery was just one of the researchers' findings. They also learned that bees don't sense bitter tastes with their feet. The results are important for understanding the honeybee sensory system and, potentially, for figuring out how pesticides might harm these important pollinators and critical lab models for cognitive research.

Sweet foot

Thanks to its impressive navigational skills, the honeybee (Apis mellifera) is a model organism used by researchers to understand the mechanisms of learning and memory. Many scientists had investigated the bee's sense of sight and smell, Giurfa said, but one sense had been left out.

"Practically nobody looked at the sense of taste in bees, which is so important for them," he told Live Science. [Tip of the Tongue: The 7 (Other) Flavors Humans May Taste]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To fill the knowledge gap, Giurfa's collaborator Maria Gabriela de Brito Sanchez of the University of Toulouse launched a painstaking series of experiments. Over the course of two years, Sanchez captured bees and stimulated their front feet with a variety of tasty (and not-so-tasty) solutions, from sweet to bitter.

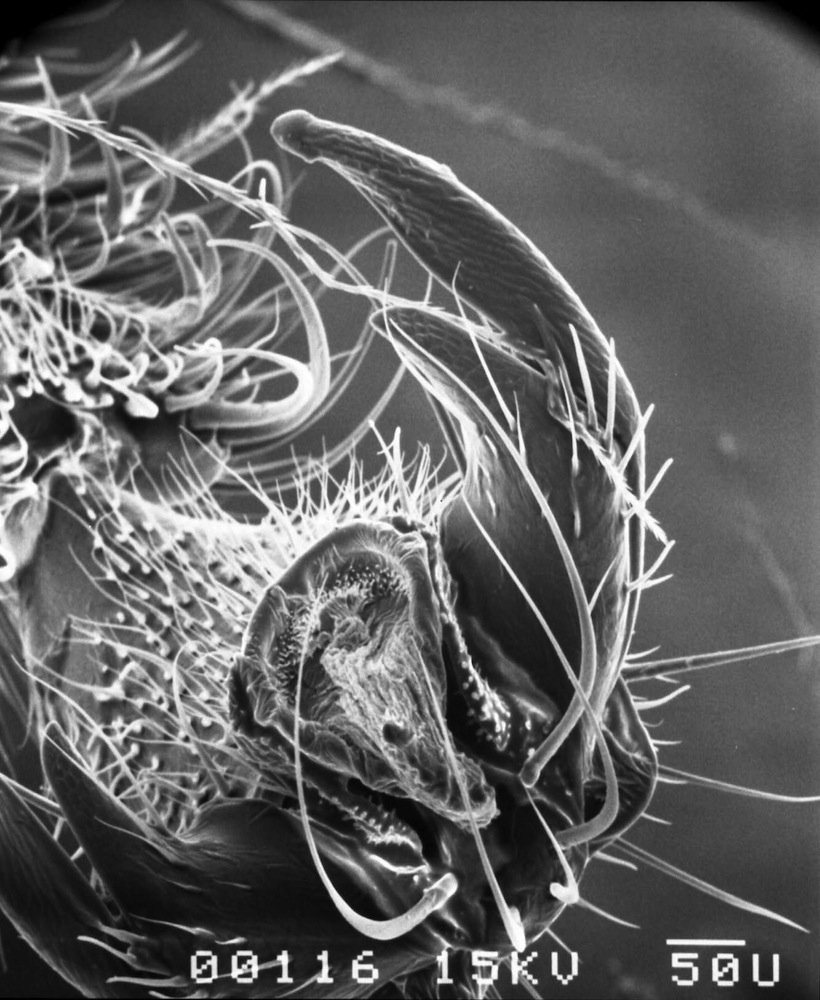

Like other insects, bees don't confine their sense of taste to their mouths. They also taste using their antennae and the surfaces of their feet. In this case, the researchers focused on the feet, dabbing sweet sucrose, bitter quinine and other solutions onto the tarsi, the end parts of the legs. Sanchez measured the bees' reactions by observing whether or not they stuck out their tongues — a tasty substance elicits a protrusion of the proboscis, while a distasteful one would lead to no response or a retraction. Sanchez also used miniscule electrodes to measure the sensory cells' reactions to different tastes.

Salt-seeking bees

Unsurprisingly, given bees' need for nectar, the insects' feet are incredibly sensitive to sugar. But they're even more attuned to salt, Giurfa said.

The bees need salt for their own metabolic processes, and to carry back to their hives to help larvae develop, Giurfa said. Thus, homeowners' trendy saltwater pools attract bees like flies to honey.

Finally, the study researchers found that bees don't seem to sense bitterness. They don't retract their tongues in response to the taste, nor do their cells show an electrical reaction to bitter substances, Giurfa said.

The findings are useful for basic research, because bees are such an important species to the understanding of the neural basis of memory and learning. But the research may also benefit the bees themselves. Bee colonies worldwide are experiencing die-offs, a mysterious phenomenon called colony collapse disorder. Pesticides and other environmental contaminants are suspects, and researchers have turned their attention to how pesticides might affect the honeybee navigation system, memory and brain function.

"They also might have serious impacts on these taste receptors," Giurfa said. He and his colleagues would like to experiment with exposing bee feet to miniscule amounts of pesticide to see how the cells respond.

The researchers report their findings today (Feb. 4) in the journal Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.