Beatlemania Hit 50 Years Ago but Why Did It Drive Girls So Mad?

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

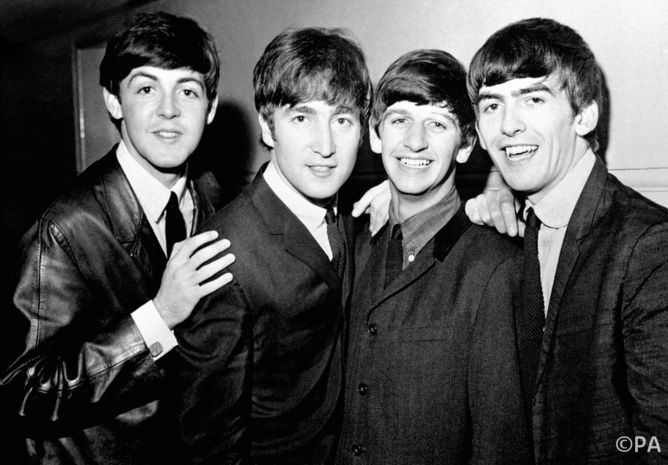

Last Sunday (Feb. 2, 2104) marks the 50th anniversary of John, Paul, George, and Ringo’s debut appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in the US. But what was it about? Was it the moptop haircuts, Cuban heels, and “yeah yeah yeahs” that turned us, our parents, or our grandparents into primeval beings whose sole purpose was to drown out the blare of a Vox AC30 amplifier?

The term “Beatlemania” has come to be associated with many things over the past half-century. Coined in October 1963 during the Beatles’ tour of Scotland, the extent of Beatlemania in the US is obvious from record sales alone.

Between the 1964 release of I Want to Hold Your Hand on the Billboard Hot 100 and the Let it Be EP in 1970, the Lads from Liverpool had a Number One single for, on average, one out of every six weeks and a top-selling album every third week.

But to most, Beatlemania conjures up a vivid image of frenzied fans, predominantly teenage girls, with facial expressions that look more like they’d witnessed a gruesome murder, and “I love George!” badges hanging on for dear life as their owners attempted to push past overwhelmed human police barricades. Lots of tears and lots of screaming.

But what can neuroscience tell us about what might have been happening in their brains?

Why do we like music?

One could argue that fanatics were interested in more than just the Beatles' musical talent, but record sales prove that people did enjoy a Beatles tune. And what about music can make us tap our toes, lulls babies to sleep, well up with emotion, dance around or stir up furious mosh pits?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In short, we know music makes us feel good; even those tunes that incite a feeling of sadness may bring us pleasure because we can relate to them. Take one 2001 study by researchers Anne Blood and Robert Zatorre at McGill University. They recruited ten individuals who had at least some formal music training. Each participant selected a song that, they claimed, gave them (good) chills.

The researchers played a 90-second excerpt of their chosen song while the subject laid in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine, a device that measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. Compared to control (neutral) sounds, music that elicits physical and emotional changes activated limbic, paralimbic, and midbrain regions. And these areas are implicated in pleasure and reward, not unlike the neural pathways that recognise yummy food, addictive drugs, and sex.

In an extension to this study published last April, Zatorre’s group used fMRI to scan the brains of 19 volunteers while they listened to the first 30 seconds of 60 songs they’d never heard before. Participants then rated how much they were willing to spend if they were to buy each song, from $0 to $2.

As it turns out, connections between a limbic system structure called the amygdala with the hippocampus (involved in learning and memory) as well as the prefrontal cortex (important for decision-making) could predict how much participants were willing to spend on each song.

The strength of these connections may partially explain why die-hard Metallica fans might completely shun hip-hop, while others may refuse to listen to anything but country. Music is a personal preference, and although we know that it brings us pleasure, that’s about the extent of our understanding.

What’s with all the crying and fainting?

Typically, we equate crying with sadness and fainting with illness.

The truth is, our brains are actually pretty dumb, and any sudden, strong emotion – from happiness to relief to stress – can elicit these vulnerable physical reactions.

Our autonomic nervous system (the “involuntary” nervous system) is divided into two branches: sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) and parasympathetic (“rest-and-digest”). Acting via the hypothalamus, the sympathetic nervous system is designed to mobilise the body during times of stress. It’s why our heart rate quickens, why we sweat, why we feel ready to run. The parasympathetic nervous system, on the other hand, essentially calms us back down.

The parasympathetic nervous system does something funny, too. Connected to our lacrimal glands (better known as tear ducts), activation of parasympathetic receptors by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine results in tear production. So for those fans relieved to finally see their Fab Four, tears were commonplace.

For others, though, the sudden activation of their parasympathetic nervous system is accompanied by something much more dramatic. A quick drop in blood pressure results from vessels widening and heart rate slowing, hence the fainting.

Fainting, crying … exactly the things you’d want your hero to see you do when you finally meet them, right?

Everybody’s crazy ‘bout a sharp-dressed man

Let’s be honest, there’s a reason Beatlemania is typified by hordes of young women: The Beatles looked good.

When Brian Epstein officially signed on as the Beatles’ manager in early 1962, the first thing he did was smarten up their stage appearance; he fitted them into Edwardian collarless suits, matching boots, and choreographed a synchronised bow at the end of each song.

According to a 2011 survey, 91% of Americans believe that a well-dressed man appears smarter, sexier, and more successful than one who is not, regardless of their overall physical attractiveness or how much money they have.

And a 1990 study of 382 college students by the University of Toledo examined just how clothes can make the man. One “attractive” and one “unattractive” man (as previously determined by a panel of females) donned a variety of clothes – from designer watches and pressed shirts to baseball caps and Burger King polos. Consistently, women rated the well-dressed man as more attractive than the sloppier one, regardless of which model sported which ensemble.

The Beatles had some pretty great hair, too. Inspired by a man they saw during a gig in Hamburg, Germany, John and Paul reportedly hitchhiked to Paris and requested the distinctive haircut.

Across cultures, long, shiny female hair is rated attractive by both genders. Evolutionary psychologists reason that the ability to grow long hair can reveal several years of a person’s health status, age, nutrition, and reproductive fitness, as vitamin deficiencies result in hair loss.

Plus, moptops eliminate any sign of androgenic alopecia, or male-pattern baldness, which studies have been associated with perceived ageing and less attractiveness. But don’t worry, men – evolutionary biologists theorise that baldness is actually a sign of dominance, longevity, and social status due to its cause – a more potent form of testosterone called DHT.

Although the fans may have drowned out the music with their shrieks, at least they still had a sight to behold.

So 50 years ago this Sunday, 73m Americans crowded around 60% of the country’s televisions to watch the Beatles’ debut, and the birth of Beatlemania. But while there are some explanations for why frenzied fans might have reacted the way they did to the Fab Four, for some the teenage shrieks and hysteria remained utterly baffling.

Jordan Gaines Lewis does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.